A University of Chicago team used CT scans and engineering vibration simulations on a 250-million-year-old Thrinaxodon liorhinus fossil to test how its skull and jaw would respond to sound. Their models show an eardrum anchored across a jaw crook could have enabled tympanic-style hearing before the three middle-ear bones detached. The researchers estimate a hearing range of about 38–1,243 Hz with peak sensitivity near 1,000 Hz at 28 dB, supporting a transitional step toward mammal-like hearing.

250-Million-Year-Old Fossil Sheds New Light on the Origins of Mammal Hearing

Modern mammals hear across a wide range of volumes and frequencies thanks to a tympanic middle ear — an eardrum plus three tiny bones. A new study by paleontologists at the University of Chicago suggests the anatomical beginnings of that system may have appeared nearly 50 million years earlier than previously thought.

The team studied a 250-million-year-old fossil of the mammal ancestor Thrinaxodon liorhinus. Using high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scans, they produced detailed 3D reconstructions of the skull and jaw and then ran engineering-style vibration simulations to test how those bones would have responded to different sound pressures and frequencies.

What the Models Show

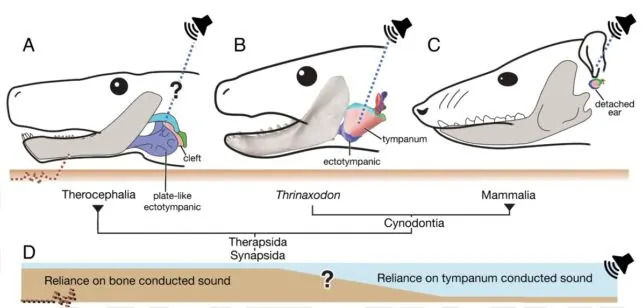

The simulations reveal that an early tympanic membrane (an eardrum) anchored across a crook in the lower jaw could have transmitted sound effectively even while the small ear bones — the malleus, incus and stapes — remained attached to the jaw. In other words, this arrangement would have been an important upgrade from pure bone-conducted hearing and represents a plausible transitional stage toward the fully detached mammalian middle ear.

Alec Wilken (University of Chicago): The CT models and biomechanical simulations allowed us to test how ear bones and jaw structures might have vibrated in an ancient fossil — something that wasn’t possible with earlier methods.

The researchers filled in missing soft-tissue properties using biologically plausible parameters from living animals, then applied engineering vibration-analysis tools (the kind used to test planes and bridges) to simulate acoustic input. Zhe-Xi Luo, Wilken’s advisor, noted that combining fossil CT data with modern material parameters makes it possible to evaluate how these long-extinct animals could have perceived sound.

Hearing Estimates And Implications

Wilken and colleagues provide a conservative estimate that Thrinaxodon could detect frequencies roughly between 38 and 1,243 Hz, with peak sensitivity near 1,000 Hz at about 28 decibels — a level between a whisper and normal conversation. That sensitivity would likely have aided prey detection, predator avoidance and possibly communication or reproductive signaling.

The study supports the idea that key functional elements of tympanic hearing were already emerging in early cynodonts during the Early Triassic, long before modern mammals evolved. The research is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and was led by Alec Wilken with Zhe-Xi Luo as a senior collaborator.

Background: Early cynodonts retained ear bones attached to the jaw; over evolutionary time those bones detached to form the specialized middle ear of mammals. Earlier suggestions that Thrinaxodon might have supported an early eardrum date back to Edgar Allin’s 1975 hypothesis, but only now have biomechanical tools been available to test the idea rigorously.

Help us improve.