Researchers at Rockefeller University sustained a 0.5 mm fragment of gerbil cochlea outside the body in endolymph- and perilymph-like fluids and a controlled chamber to study hearing mechanics. They observed hair-bundle-driven amplification and found direct evidence that mammalian hearing operates near a Hopf bifurcation, a dynamical criticality first proposed by A. James Hudspeth. This ex vivo platform offers a new way to probe the active process of hearing and could guide studies aimed at treating sensorineural hearing loss.

Researchers Keep a Mammalian Inner Ear Alive Outside the Body, Confirming a Key Amplification Mechanism

Researchers at Rockefeller University have, for the first time, sustained a fragment of a mammalian inner ear outside the body and directly observed the tiny mechanical and electrochemical processes that amplify sound.

Using a 0.5 mm sliver of gerbil cochlea taken at a developmental stage before the cochlea fused to the temporal bone, the team maintained the tissue in a custom chamber with fluids analogous to endolymph and perilymph and controlled temperature and membrane voltages. Two companion papers describe the technical method (Hearing Research) and the physiological findings (PNAS).

Direct Evidence of a Long-Held Theory

One major result is clear confirmation that mammalian hearing operates near a dynamical critical point known as a Hopf bifurcation — a regime in which mechanical instability converts to self-sustained oscillation, producing amplification. The late A. James Hudspeth first described this mechanism in the bullfrog cochlea decades ago, and these experiments provide the first direct mammalian evidence supporting his long-standing hypothesis.

‘This shows that the mechanics of hearing in mammals is remarkably similar to what has been seen across the biosphere’ — Rodrigo Alonso, co-first author, Rockefeller University.

What the Scientists Observed

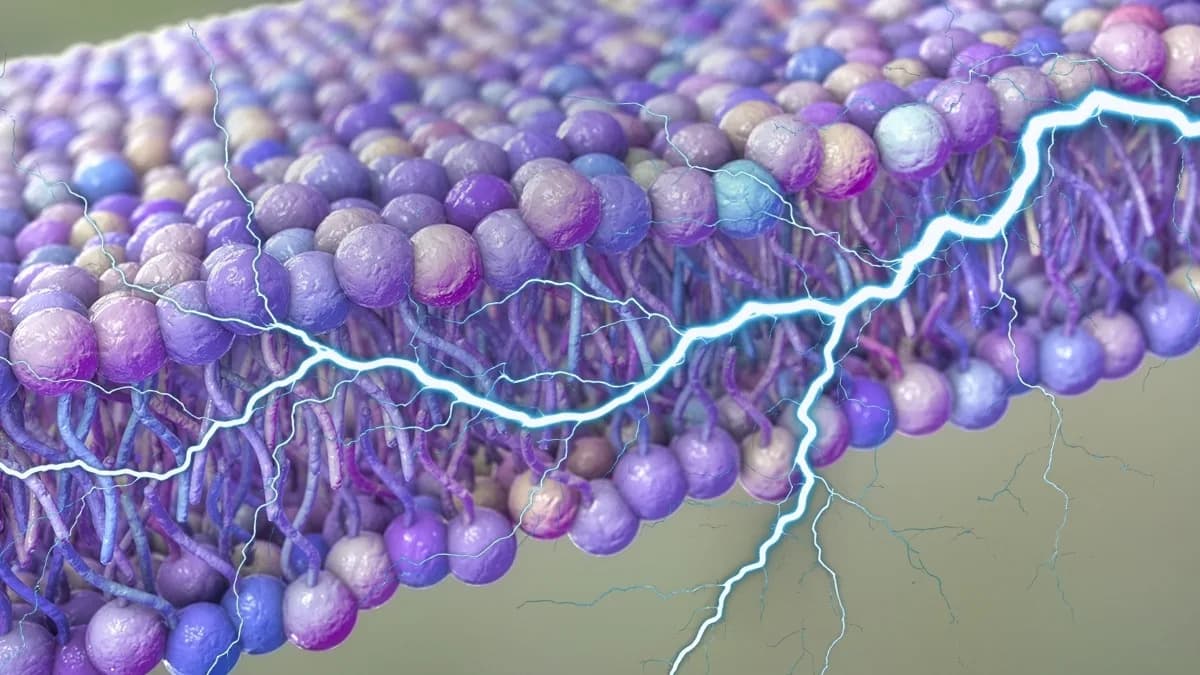

The cochlea contains roughly 16,000 hair cells; each hair cell bears bundles of stereocilia just 10–50 micrometers long. Under the microscope in the recreated ionic environment, researchers watched hair bundles act cooperatively to feed energy into mechanical vibrations while responding to changes in membrane voltage. They recorded the so-called active process — behavior consistent with operation near a Hopf bifurcation — which amplifies faint sounds and sharpens frequency selectivity.

‘We can now observe the first steps of the hearing process in a controlled way that was previously impossible,’ — Francesco Gianoli, co-first author. ‘The experiment required extraordinary precision to protect both mechanical fragility and electrochemical integrity.’

Why This Matters

By keeping a mammalian inner-ear fragment alive and functional ex vivo, scientists now have a powerful platform to probe the earliest mechanical and electrochemical steps of hearing and to watch how those processes fail. Sensorineural hearing loss — commonly caused by damage to hair cells — has no approved drug therapies that restore hearing, in part because the active amplification process is not fully understood. This new preparation should accelerate mechanistic studies and inform future therapeutic strategies.

Next Steps

Future work will refine the preparation, test how damage or drugs alter the active process, and explore translation to other mammalian models. The technique opens a path toward a deeper understanding of hearing and, ultimately, interventions for sensorineural hearing loss.

Help us improve.