Researchers have shown that fragmentation across materials follows a universal power law. Emmanuel Villermaux (University of Aix-Marseille) demonstrated that global kinematics, not microscopic structure, determine how space is partitioned when objects break. Small fragments consistently outnumber large ones, and counts scale predictably with applied force. The finding could improve models for earthquakes, debris, and other systems, though some fluids and plastics are exceptions.

Everything Breaks the Same Way — The Universal Power Law of Fragmentation

Randomness pervades the universe, yet researchers keep finding simple, powerful rules beneath apparent chaos. One striking example: the way objects fragment. Recent work shows that whether a glass mirror shatters or a soap bubble pops, the counts of small and large fragments follow the same mathematical pattern — a power law — driven by geometry and global motion rather than microscopic details.

A Geometric Rule for Breakage

Emmanuel Villermaux of the University of Aix-Marseille demonstrated in a paper published last November that fragmentation is governed primarily by global kinematics. Instead of focusing on microstructure, Villermaux modeled how forces partition space during breakage. The result: the geometry of partitioning is invariant, while the magnitude of the force scales fragment sizes and counts.

Key idea: Small fragments always outnumber large fragments, and their relative counts follow a predictable power law.

Power Law vs. Normal Distribution

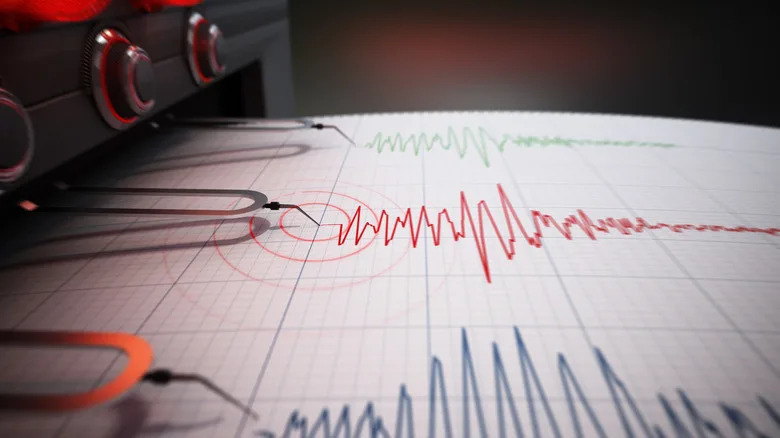

Unlike a normal (Gaussian) distribution, where values cluster around a single average, a power law has no strict upper bound and the mean is not the most common outcome. That pattern explains why many tiny events and a few extreme ones coexist in phenomena such as earthquakes, tsunamis, and nuclear accidents: the rare, large events dominate averages in ways a Gaussian model cannot capture.

What Villermaux Found

- Fragment counts by size follow a universal power law regardless of material or scale.

- The applied force determines the scale (how many fragments and their sizes) but not the underlying partitioning geometry.

- This approach lets researchers estimate the expected numbers of small, medium, and large fragments given the force and global kinematics.

Applications and Limits

Because power laws appear across many domains, Villermaux's findings could refine models in several fields: locating critical damage zones in earthquakes, improving debris forecasts in engineering, and informing analogies used in epidemiology or social science models of fragmentation. However, not every material follows the rule perfectly: some continuously flowing liquids (for example, a steady stream of tap water) and certain plastics can deviate from the predicted pattern.

In short, fragmentation looks less like chaotic exception and more like geometric inevitability: a simple mathematical law shaping how the world breaks.

Help us improve.