Japan’s recent clash with Beijing — which triggered export curbs on more than 1,100 products — highlights why supply‑chain resilience matters. Through state investment, recycling, stockpiles and overseas projects, Japan has cut rare‑earth dependence from nearly 90% in 2010 to about 60% today. Germany is now mapping thousands of products for China reliance, and the lesson for the UK is to identify dependencies and build legal and financial tools to diversify before deepening trade with Beijing.

How Japan’s ‘De‑Chinafying’ Playbook Should Shape Starmer’s China Strategy

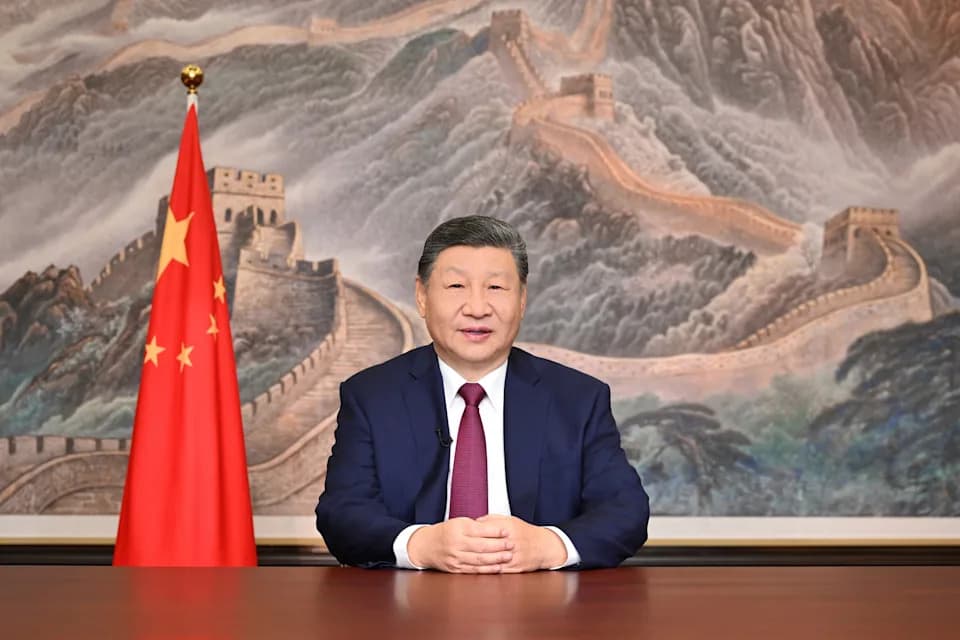

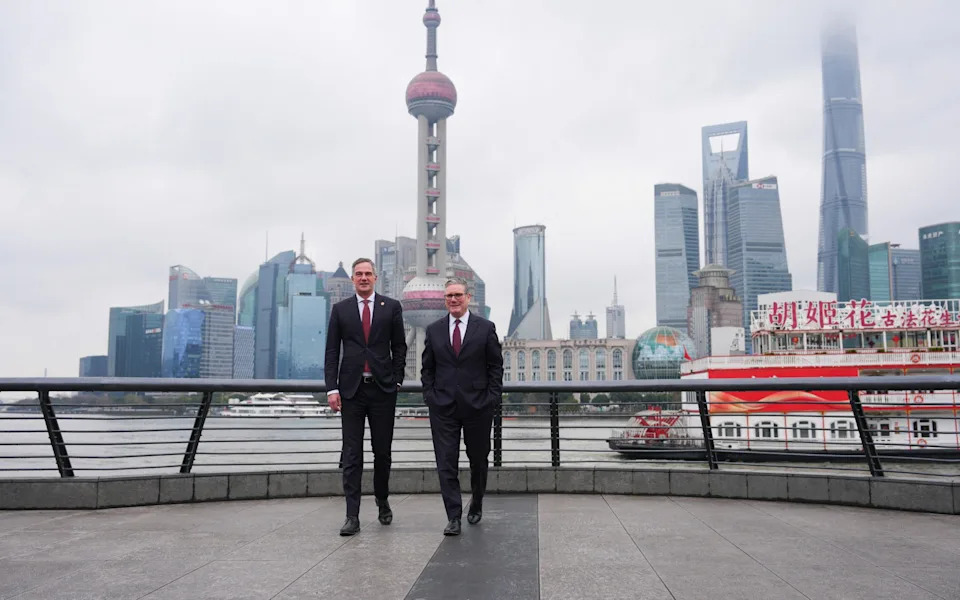

Ever since David Cameron toasted Xi Jinping and hailed a 'golden era' in Sino‑British relations, opinion has been divided over what went wrong. As Sir Keir Starmer seeks his own diplomatic reset in Tokyo, Japan’s recent experience shows that limited trade exposure to Beijing can be a strategic starting point for diversification rather than a shortcoming to be immediately reversed.

What Triggered the Crisis

After Sanae Takaichi — Japan’s new prime minister often dubbed Asia’s 'Iron Lady' — warned that an attack on Taiwan could pose an 'existential threat' to Japan, Beijing responded by restricting exports of so‑called 'dual‑use' items to Japan. The blacklist runs to more than 1,100 products, from pharmaceuticals and chemicals to AI‑related technologies, software and rare‑earth minerals, giving China leverage to impose targeted shortages or delays.

Economic Risk And Preparedness

Japanese economists rushed to quantify the hit. If curbs were limited to a narrow set of rare earths for a year, the direct cost might be under 1% of GDP. But if China widened the restrictions, the Daiwa Research Institute warned losses could approach £85bn and cost up to two million jobs. Those forecasts would almost certainly be worse without Tokyo’s prior efforts to 'de‑Chinafy' critical supply chains after an earlier embargo in 2010.

Japan’s Response: Investment, Stockpiles And Alternatives

Since 2010, Japan has pursued a pragmatic 'less China' approach rather than 'no China.' The government created the publicly owned Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security to build strategic stockpiles and develop alternative supplies. Tokyo has funded recycling, backed new refineries (including Europe’s Caremag), invested in overseas mines such as in Namibia, and become a major investor in Australia’s Lynas — the largest rare‑earth producer outside China.

Research and industrial innovation are also bearing fruit: Japanese companies including Honda and Nissan are increasingly using magnets and motor designs that reduce or eliminate rare‑earth content, and a Honda‑backed developer has unveiled an EV motor claimed to be significantly more efficient than conventional designs dependent on Chinese parts. Overall, Japan has cut its reliance on Chinese rare earths from nearly 90% in 2010 to roughly 60% today — progress, though not yet a full replacement.

Legal Tools And Strategic Planning

Japan’s Economic Security Promotion Act (2022) requires ministries to map product‑by‑product dependencies, gives authorities power to veto investments in sensitive sectors, and provides subsidies to encourage reshoring and resilience. That mix of industrial policy, public investment and legal levers is now being studied and partly adopted by other major economies.

Germany, for example, is analysing more than 14,300 product groups and has already flagged roughly 200 items where China supplies at least half of domestic needs. Berlin is preparing legislation that would allow remedial interventions to reduce systemic exposure — a response shaped by years of industrial cooperation with China that left some sectors vulnerable.

Implications For The UK

The key lesson for Britain is pragmatic: before deepening trade with Beijing, policymakers should map existing dependencies, invest in alternatives, and create mechanisms to nudge — and if necessary compel — companies to diversify supply chains. That means targeted subsidies, strategic stockpiles, support for research into substitutes, and legal powers to screen or limit foreign investment in critical technologies.

Political Dimension

Beijing’s export controls may also be politically motivated. Some analysts see the restrictions as an attempt to weaken Ms Takaichi ahead of a snap election; instead, early polls suggest she may secure a strong mandate. Asked about her Taiwan comments, Ms Takaichi stood firm:

'If the US military … came under attack and Japan did nothing but ran away, then the Japan‑US alliance would fall apart.'

Conclusion

Japan’s experience illustrates that supply‑chain resilience is not an automatic byproduct of globalization: it requires sustained public investment, industrial policy, and legal frameworks. For Starmer and other Western leaders, the pragmatic path is clear — treat limited exposure to China as a strategic vantage point for diversification, and put in place the tools to manage dependence before it becomes a vulnerability.

Help us improve.