The U.S. is seeing a decline in drinking among younger adults and a rise in alcohol-free social spaces, yet new federal guidance opts for a vague "consume less" message rather than a strict limit. Dr. Mehmet Oz defended alcohol's role as a "social lubricant," prompting pushback from public-health experts who warn about links to cancer and liver disease. Evidence on moderate drinking is mixed: some studies note social and heart-related benefits while others emphasize cancer and liver risks. The debate centers on how to balance social value, health risks, industry influence and changing cultural habits.

Alcohol's Double Edge: Social Glue or Public-Health Hazard?

Alcohol use in the United States is shifting: younger adults are drinking less, sober bars and alcohol-free clubs are emerging in cities, nonalcoholic beer sales are rising, and sobriety influencers have gained prominence on social media. Yet the Trump administration's new dietary guidance — which advises Americans to "consume less alcohol for better overall health" rather than setting a specific daily limit — has reignited debate over alcohol's role in society.

The New Guideline And The Controversy

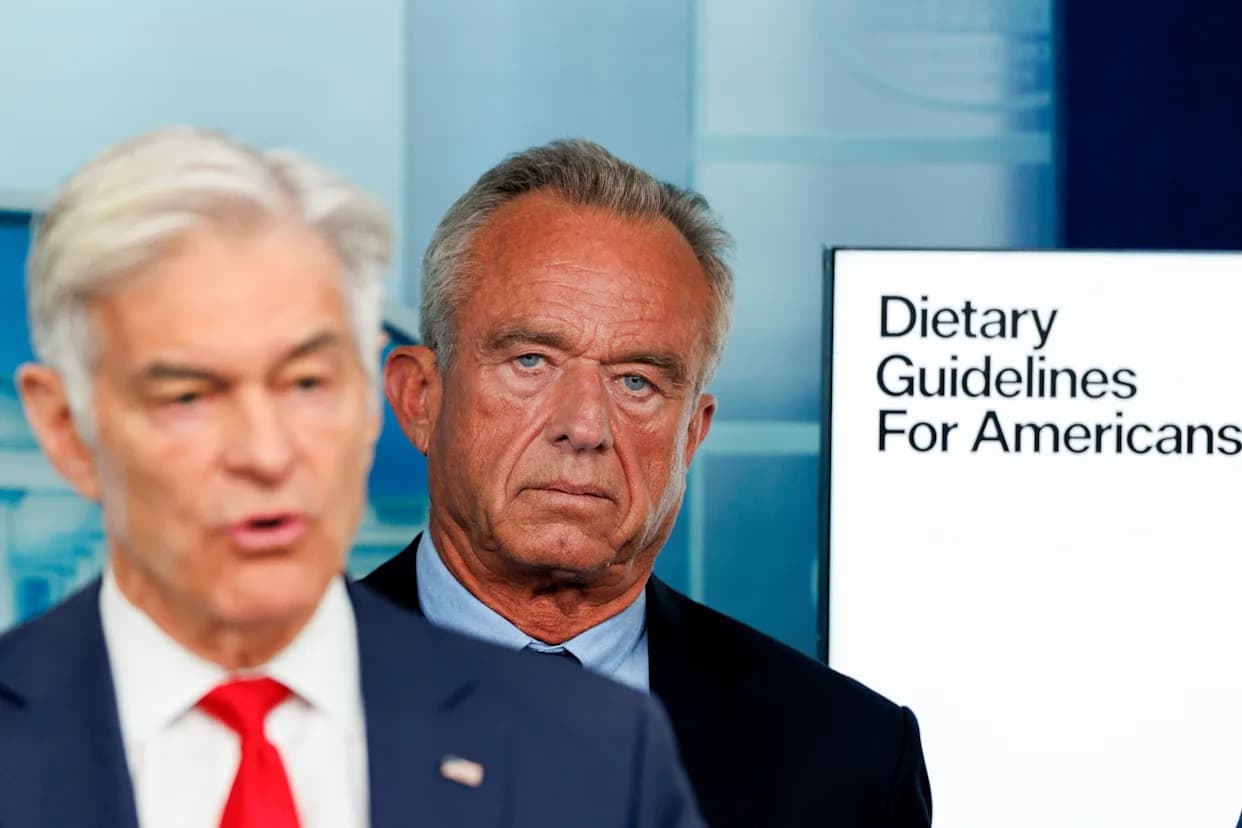

At a White House briefing on Jan. 7, Dr. Mehmet Oz, administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, defended a social role for alcohol, calling it a "social lubricant" that can help people bond. His comments prompted sharp responses from public-health researchers and sober advocates who argue that emphasizing social benefits risks downplaying well-established physical harms.

“Alcohol is a social lubricant that brings people together… In the best-case scenario, I don’t think you should drink alcohol, but it does allow people an excuse to bond and socialize,” Oz said.

What The Science Says

Scientific evidence is mixed on how much alcohol — if any — is safe. The World Health Organization maintains there is no safe level of alcohol consumption and links even light drinking to increased cancer risk. Studies also connect regular alcohol use to liver damage and other illnesses. Two recent federal reports drew different conclusions: one (Dec. 2024) associated moderate drinking with lower all-cause and heart disease mortality but a higher breast cancer risk, while another (Jan. 2025) warned that even one daily drink may raise the risk of liver cirrhosis and certain cancers.

Research on alcohol's social effects is also nuanced. Some laboratory and field studies suggest light-to-moderate drinking can boost positive mood and ease initial social bonding. But experts caution these social benefits do not negate the documented physical harms.

Voices From Both Sides

Public-health scientists such as Priscilla Martinez of the Alcohol Research Group argue there is no clear evidence that drinking produces deeper friendships or lasting happiness. Martinez also says her group's draft report — which linked higher alcohol consumption to greater disease and mortality risk — was not published by the administration during the guideline update process.

Sober advocates and entrepreneurs counter that meaningful social life does not require alcohol. Rachel Hechtman, a sober life coach and content creator, and leaders of new dry spaces like The Maze in New York City say alcohol-free environments can foster more intentional, lasting connections.

“Without alcohol as a buffer or crutch, people tend to be more present and more intentional,” said Justin Gurland, founder of The Maze.

Industry, Culture And Trends

The alcohol industry has leaned into the social argument, with campaigns from brands such as Dos Equis and Heineken framing beer as a way to connect. Meanwhile, analysts note a decline in overall drinking: a Gallup survey found 54% of U.S. adults reported consuming alcohol as of July, down from 62% in 2023. Market forces, cultural shifts like #SoberTok, and economic pressures are all cited as contributing factors.

What Comes Next

The debate highlights a policy challenge: how to weigh potential social benefits of moderate drinking against clear evidence of physical harm. Public-health experts suggest expanding alcohol-free social spaces, investing in public gathering places like parks and community centers, and ensuring dietary guidelines are transparent about the evidence and uncertainties that informed them.

Bottom line: The conversation is not just about individual choice; it's about how society balances social needs, industry influence, and public health evidence as drinking habits evolve.

Help us improve.