The 2025–2030 Dietary Guidelines advise Americans to cut back on ultra-processed foods, but experts warn the guidance lacks a clear, uniform definition and practical tools for consumers. Public-health leaders highlight that more than half of U.S. calories now come from ultra-processed products and say the FDA and USDA must develop consistent definitions and labeling standards. They urge pairing dietary advice with education and policy solutions — such as front-of-pack labels and reforms to subsidies and marketing — to make the guidance actionable.

Experts: New Dietary Guidelines Urge Cuts To Ultra-Processed Foods — But Definitions, Tools Still Lacking

The federal 2025–2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans urge people to reduce intake of ultra-processed foods, but public-health experts say the guidance risks falling short without a clear, uniform definition, consumer tools and broader policy supports.

What the Guidelines Say

Published on Jan. 7 by U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the updated guidelines for the first time advise Americans to avoid "highly processed foods," listing examples such as packaged, prepared, ready-to-eat items and sugar-sweetened beverages like soda, fruit drinks and energy drinks. The guidance — revised every five years — shapes federal feeding programs, from school meals to nutrition-assistance benefits.

Experts Worry About Lack Of Definition

"In short, we are asking individuals to eat less of nearly 70% of the food supply without giving them the tools, clarity, or systemic support to do so," said Alexina Cather, director of policy and special projects at the Hunter College New York City Food Policy Center. Cather and other public-health leaders argue that issuing guidance without a shared, operational definition for "ultra-processed foods" makes it hard for consumers, researchers and policymakers to act.

"This is not just a semantic debate. If the purpose of the Dietary Guidelines is to improve population health, there should have been a clear definition and a public education effort rolled out alongside the 2025–2030 edition," Cather told ABC News.

How Experts Describe Ultra-Processed Foods

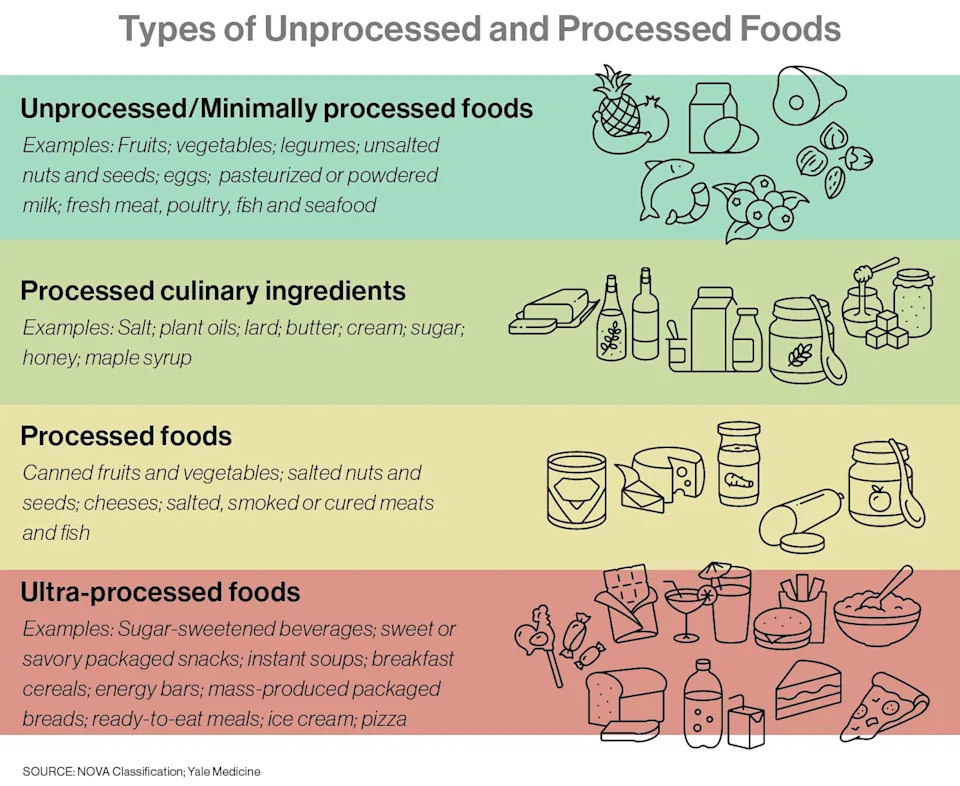

There is not yet a single, universally accepted U.S. definition for ultra-processed foods. Dr. Nate Wood, an assistant professor of medicine at Yale School of Medicine, described ultra-processed foods as products made with industrial ingredients — items a typical consumer "would not have at home in the kitchen." He referenced the NOVA food-classification system, which categorizes foods into four groups by level of processing; NOVA's Group 4 corresponds to what many experts call ultra-processed foods.

Data And Regulatory Moves

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported last August that Americans obtain more than half of their daily calories from ultra-processed products. In response to definitional gaps, the Food and Drug Administration last year committed to studying ultra-processed foods and working with the U.S. Department of Agriculture to establish a consistent definition to guide policy and programs.

Practical Challenges For Consumers

Experts acknowledge the guidance is directionally correct but worry many shoppers will struggle to identify which packaged items qualify as ultra-processed. "Not all ultra-processed foods are bad," Wood said, noting examples such as some whole-grain breads or tofu that can be health promoting. To help consumers, Wood recommends clearer front-of-pack labeling — an approach used in some European countries — and advises checking ingredient lists and levels of fat, sugar and salt.

Broader Policy And System Issues

Cather and others emphasize that individual advice must be paired with structural changes. Ultra-processed products dominate shelf space, advertising and price promotions and are often prioritized by corporate practices and subsidy structures, making them cheaper and more accessible in many communities. Without addressing food-system drivers — subsidies, corporate marketing, retail practices and economic inequities — experts say dietary guidance alone will have limited impact.

A few localities and states have piloted policies such as front-of-pack labeling or marketing restrictions to help consumers identify products high in additives, sugar and sodium, but those efforts remain limited. Observers also point to recent state moves such as a California bill banning certain artificial dyes in school foods as examples of targeted policy action.

What Comes Next

Public-health leaders call for a coordinated effort: a clear, operational definition of ultra-processed foods; consumer education and labeling tools; and policy changes that address the economic and marketing forces shaping food choices. Those steps, they say, would make the guidance more actionable and equitable.

Help us improve.