The new federal dietary guidance drops numeric alcohol limits (previously two drinks per day for men, one for women) in favor of a vague recommendation to "consume less alcohol for better health." Dr. Mehmet Oz claimed there is no scientific basis for specific limits, but a government-commissioned Alcohol Intake & Health Study — later shelved and not publicly released in final form — found harms begin at low levels and rise steeply with greater intake. Public-health experts and independent reviewers warn the change favors the alcohol industry and may undercut clearer, evidence-based advice.

Dr. Oz Says No Data Supports Drinking Limits — The Evidence Tells a Different Story

The latest federal dietary guidelines replaced specific numeric alcohol limits with a vaguer admonition to "consume less alcohol for better health," prompting criticism from public-health experts who say the guidance effectively removes clear, evidence-based advice on safe drinking levels.

What Changed

Previously, U.S. guidance recommended no more than two drinks per day for men and one drink per day for women. The new guidance drops those numeric caps and instead advises the public to "consume less alcohol for better health," while continuing to recommend complete abstinence for certain groups such as pregnant people and those with a history of alcohol use disorder.

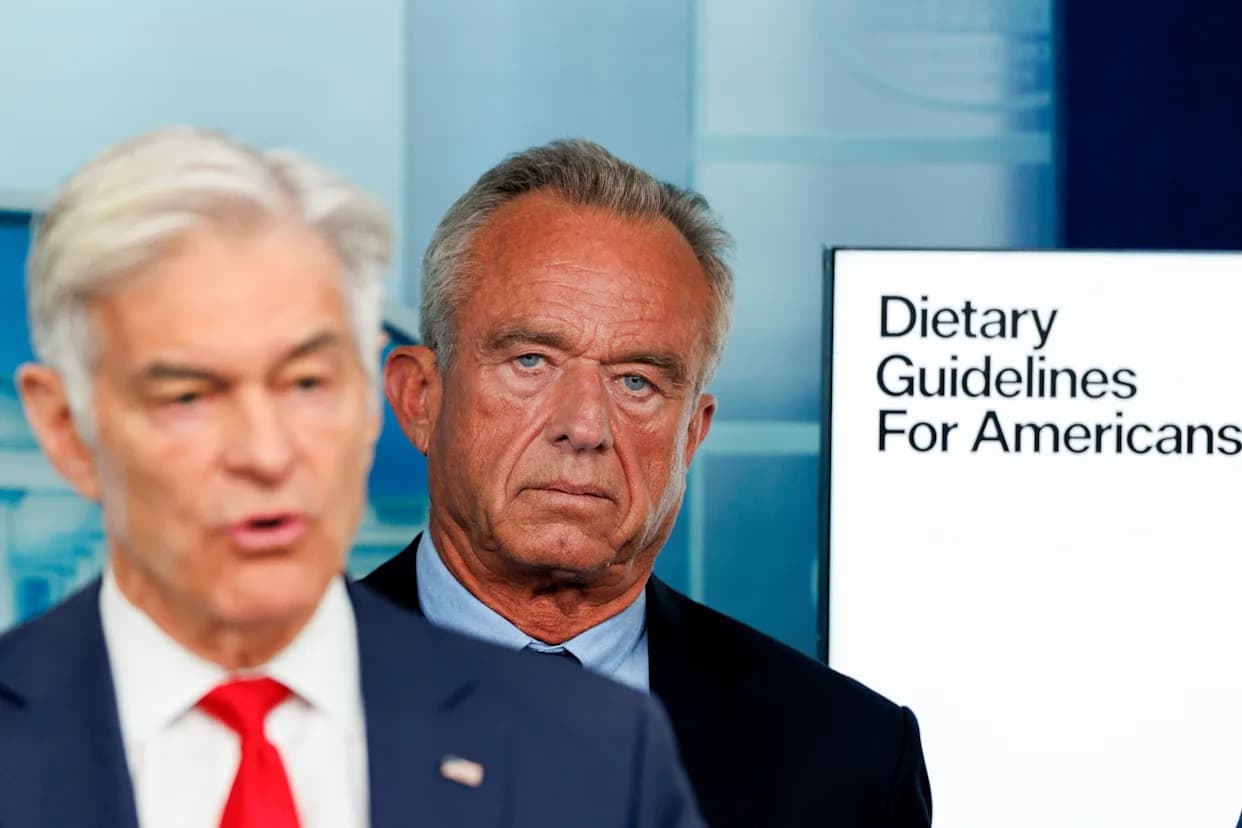

What Officials Said

During the announcement, Dr. Mehmet Oz, who oversees the Medicare and Medicaid programs, argued that there was "no scientific basis" for precise numeric limits. "So there is alcohol in these dietary guidelines, but the implication is, don’t have it for breakfast," he said. He further stated that the historic one-drink/ two-drink thresholds lacked solid data — a claim that conflicts with government-commissioned research.

What The Research Shows

Contrary to Dr. Oz’s statement, a government-commissioned "Alcohol Intake & Health Study" — completed as a draft near the end of the prior administration — concluded that harmful health effects begin at low levels of consumption and increase sharply as intake rises. The draft reported that a man who drinks one alcoholic beverage per day faces roughly a 1-in-1,000 chance of dying from an alcohol-related cause (including alcohol-associated cancers, liver disease, or fatal crashes). That risk was estimated to climb substantially with higher consumption — to about 1-in-25 for two drinks per day in the study’s analysis.

Another independent review by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, published in December 2024, reached a different, more cautious interpretation: it characterized alcohol’s health effects as marginal for some outcomes but stressed important limitations and called for careful interpretation. The National Academies authors later published a commentary in JAMA warning readers not to use their report as an excuse to loosen drinking limits.

Politics, Industry Pressure, And A Shelved Report

The Alcohol Intake & Health Study’s final version has not been released by the current administration; reporting indicates the draft was effectively sidelined even as officials said it would inform the dietary guidance. The delay and the change in language have been welcomed by alcohol manufacturers and criticized by public-health advocates, who argue the move amounts to a policy victory for the industry.

"The federal government’s own report made it clear that reducing consumption to less than two drinks per day dramatically reduces the chance of dying due to alcohol," said Mike Marshall, president and CEO of the U.S. Alcohol Policy Alliance.

Why This Matters

Public-health researchers increasingly say there is no completely "safe" level of alcohol consumption, and international bodies such as the World Health Organization have taken similarly cautious positions. In the U.S., alcohol is associated with more than 170,000 deaths per year, and experts worry that removing clear numeric guidance will weaken public understanding of risk and make it harder for clinicians and individuals to make informed choices.

Bottom line: The administration’s removal of explicit drink limits reflects political and industry pressures as much as unresolved scientific debate. Several government and independent analyses indicate that risks rise even at low levels of consumption — evidence that many public-health experts say supports clear, conservative guidance, not vagueness.

Help us improve.