Bangladesh’s general election on February 12, 2026 has become a two-way contest after the interim government banned Sheikh Hasina’s Awami League. Jamaat-e-Islami — long marginalised and harshly repressed under Hasina — has re-emerged in a coalition with the National Citizen Party and is closing the gap with the BNP in recent polls. Critics warn Jamaat’s wartime record and Islamist roots remain major liabilities, while the party says it will govern within the secular constitution and focus on reform. Analysts expect Jamaat to improve its showing but doubt it can win an outright majority; the result will also influence Dhaka’s ties with India and Pakistan.

Jamaat-e-Islami’s Comeback: Could Bangladesh’s Islamist Party Lead the Country After Feb. 12?

Dhaka, Bangladesh — For the first time in his life, Abdur Razzak, a 45-year-old banker from Faridpur, believes the political party he supports could realistically lead a governing coalition. Campaigning with Jamaat-e-Islami’s “scales” emblem, Razzak told reporters that many voters he met were "united in voting" for Jamaat — a sign of the party’s growing momentum ahead of Bangladesh’s national election on February 12, 2026.

Why This Election Matters

The February vote is the first national election since a student-led uprising toppled long-time former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina in August 2024. The interim government led by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus has banned Hasina’s Awami League, transforming the contest into a largely bipolar race between the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and an electoral coalition led by Jamaat-e-Islami together with the National Citizen Party (NCP) and other allies.

Polls, Momentum and Organization

Recent surveys suggest Jamaat is closing the gap with the BNP. A December poll by the International Republican Institute put BNP support at 33% and Jamaat at 29%. A later joint poll by Bangladeshi agencies — NarratiV, Projection BD, the International Institute of Law and Diplomacy (IILD) and the Jagoron Foundation — found BNP at about 34.7% and Jamaat at 33.6%. Party officials say Jamaat has around 20 million sympathizers and roughly 250,000 registered members ("rukon").

From Marginalisation to Revival

Jamaat-e-Islami’s rise would be a dramatic reversal. Under Hasina’s 15-year government the party was banned, senior leaders were tried by the International Crimes Tribunal, and several were executed. Thousands of members were reportedly detained, disappeared, or died in custody. The tribunal itself has been controversial, with human rights groups raising due-process concerns. In an ironic twist, the tribunal later sentenced Hasina to death in November over the 2024 crackdown; she fled to India and New Delhi has so far refused to extradite her.

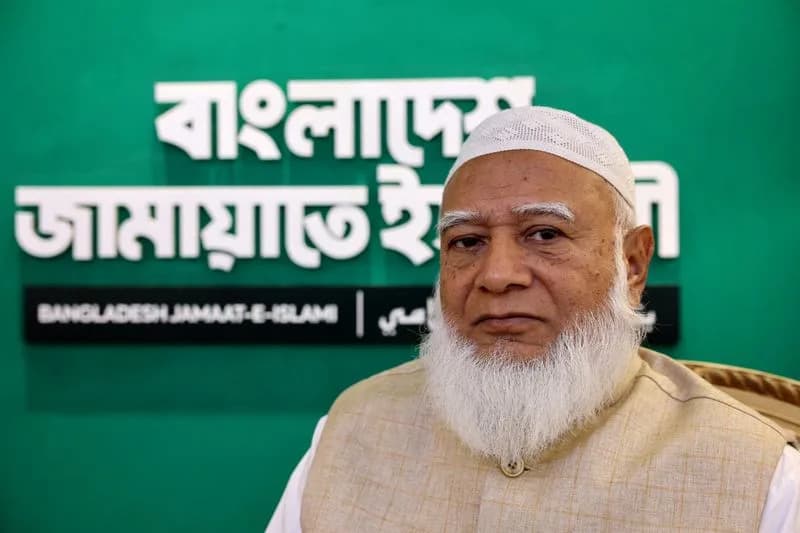

After the 2024 uprising and the lifting of Jamaat’s ban, the party — led by Shafiqur Rahman (chief), Syed Abdullah Mohammed Taher (deputy chief) and Mia Golam Porwar (secretary-general) — reorganized quickly, emphasizing discipline, grassroots mobilization and a platform of reform and good governance.

“Over the last 55 years, Bangladesh has mainly been ruled by two parties: the Awami League and the BNP,” Jamaat deputy chief Taher told Al Jazeera. “People have long experience with both, and many feel frustrated. They want a new political force to govern.”

History And Political Liability

Jamaat’s historical record remains a major liability. Founded by Syed Abul Ala Maududi in 1941, the party opposed Bangladesh’s 1971 independence and supported Pakistan during the war. Senior Jamaat figures were implicated in organizing paramilitary units that committed mass atrocities — a legacy that continues to provoke deep public anger and political controversy. The party was banned after independence in 1972 and reinstated in 1979, later partnering with the BNP in successive coalitions during the 1990s and 2000s.

Policy Positioning and Outreach

Jamaat leaders insist they will govern within Bangladesh’s secular constitution and focus on tackling corruption and improving governance rather than enforcing religious law. Taher rejects labels such as "conservative" and describes the party as a "moderate Islamist force" committed to constitutional reforms. The party has also sought to broaden its electoral appeal: for the first time it fielded a Hindu candidate, Krishna Nandi, in Khulna and has emphasized minority rights in some campaign messages.

Analysts’ Views And Regional Implications

External analysts urge caution. Asif Bin Ali, a geopolitical analyst, noted that many Bangladeshi voters are increasingly religious yet pragmatically prefer politicians to clerics — meaning religiosity does not automatically translate into support for a hardline Islamist administration. Thomas Kean of the International Crisis Group argued Jamaat’s strongest appeal may be its image as a cleaner, more disciplined alternative to the established parties, but he remains skeptical Jamaat can win an outright majority given its poor historical electoral record.

A Jamaat-led government could also affect Bangladesh’s foreign relations. Observers warn that ties with India might be harder to reset under Jamaat than under a BNP-led administration, given domestic politics in both capitals. At the same time, Dhaka has already begun rebuilding ties with Pakistan since Hasina’s fall, engaging in renewed diplomacy and talks on trade and transport.

What’s At Stake

For Jamaat supporters the election is a test of whether a party long defined by exclusion and controversy can convert organizational resilience into mainstream legitimacy. For critics, it is a moment to assess whether Bangladesh is willing to entrust a party with a divisive past with national leadership. As one academic put it, the contest may ultimately be decided less by ideology and more by competing promises of reform and stability.

Help us improve.