Eric and Wendy Schmidt will privately fund Lazuli, a new space telescope with a 3.1‑meter mirror and instruments including a wide‑field camera, spectrograph and coronagraph, planned to operate from an elliptical orbit between 77,000 km and 275,000 km. Launch is targeted for 2028 with operations expected in 2029. The Schmidts will also back three ground facilities—the Argus Array, a 1,600‑dish radio array, and LFAST—illustrating how private capital and lower launch costs are reshaping space science and easing NASA’s financial burden for successor capabilities.

Eric Schmidt Funds 'Lazuli' Telescope and a Network of Observatories, Accelerating Private Space Science

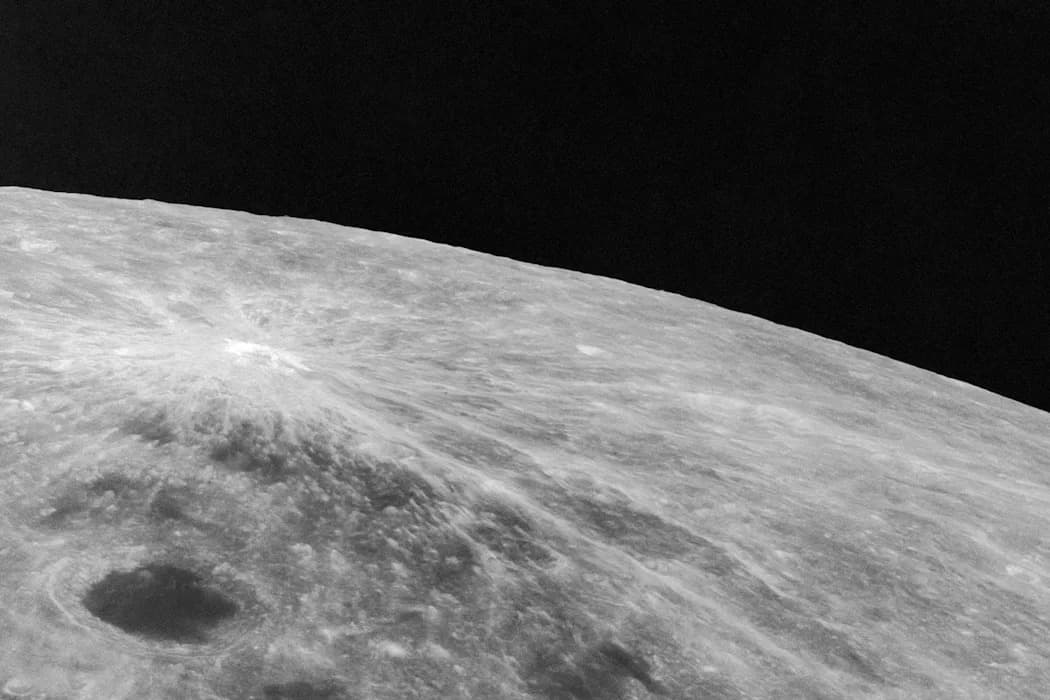

Former Google CEO Eric Schmidt and his wife, Wendy, announced plans to privately finance multiple new observatories, headlined by a space telescope called Lazuli, intended as a successor to the Hubble Space Telescope when it reaches the end of its operational life in the early 2030s.

Lazuli’s Design and Mission: According to reporting, Lazuli will feature a 3.1‑meter primary mirror—larger than Hubble’s 2.4‑meter mirror but smaller than the James Webb Space Telescope’s 6.6‑meter mirror—and will carry a wide‑field camera, a broadband integral‑field spectrograph and a coronagraph. The planned orbital profile is an elliptical orbit with a perigee of about 77,000 km and an apogee near 275,000 km, placing the telescope well above the congested low‑Earth‑orbit region where constellations such as Starlink operate. That orbit should provide a cleaner, near‑continuous view of the sky and allow round‑the‑clock control. The targeted launch year is 2028 with science operations expected to begin in 2029.

Cost Context And NASA’s Position: Schmidt has said Lazuli will cost substantially less than Hubble. For context, NASA reported Hubble’s lifetime cost at roughly $16 billion as of 2021 (a figure that excludes some deployment and servicing mission costs). Comparing historic launch costs, space shuttle flights at their peak were estimated between $500 million and $1.5 billion per flight; modern heavy‑lift rockets such as Falcon Heavy are a fraction of those prices, which bolsters claims that launch costs for a new telescope today could be much lower than past programs. Private financing can relieve NASA of the direct expense of replacing Hubble, though scientific partnerships and data-sharing arrangements remain possible and valuable.

Ground-Based Network: The Schmidts’ plans extend beyond Lazuli to several ground projects: the Argus Array (a proposed network of about 1,200 small telescopes with roughly 11‑inch mirrors, likely sited in Texas), a Digital Stack Array (DSA) style radio telescope consisting of about 1,600 dishes with ~6‑meter antennas to cover roles once filled by Puerto Rico’s Arecibo, and LFAST, a scalable large‑aperture spectroscopy facility likely to be based in Arizona. Together, these installations aim to provide complementary optical and radio capabilities to Lazuli’s space‑based observations.

Private Space Science Trend: Lazuli and the ground projects are part of a broader expansion of privately funded space science. Dramatic reductions in launch costs—driven largely by companies such as SpaceX, and complemented by other commercial launch providers—plus philanthropic capital are enabling new models for building and operating scientific facilities. Recent private and commercial milestones include crewed launches on SpaceX Crew Dragon, private lunar landers such as Firefly Aerospace’s Blue Ghost, and planned commercial space stations such as Vast Space’s Haven‑1.

Not every private mission succeeds: Astroforge’s asteroid prospecting mission Odin underperformed in early 2025, and other missions remain in development, for example Rocket Lab and MIT’s Venus Life Finder, which is scheduled to launch no earlier than summer 2026. Some projects operate with NASA support or under NASA programs like Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS); others proceed without direct agency involvement.

Why Private Funding Matters: The rise of private funding and commercial partners addresses several vulnerabilities in the traditional government‑led model for space science. In 2025, proposed budget cuts to NASA science programs illustrated how political shifts can threaten long‑term research investments. Private capital can provide alternative funding sources, accelerate technology development, and foster new collaborations—though it also raises questions about access, data sharing and long‑term stewardship of scientific facilities.

Looking Ahead: The 21st century is increasingly defined by a hybrid space ecosystem in which government agencies, private companies and philanthropic funders each play roles. Ambitious private goals—such as plans by companies to support human settlements on Mars—will likely involve public‑private partnerships for technologies like advanced propulsion and nuclear power. Lazuli and the Schmidts’ observatory projects are an early example of how philanthropic investment can shape the future of astronomical research.

Author Note: Mark R. Whittington, a frequent commentator on space policy, has written several political studies of space exploration, including "Why Is It So Hard to Go Back to the Moon?", "The Moon, Mars and Beyond" and "Why Is America Going Back to the Moon?" He also blogs at Curmudgeons Corner.

Copyright 2026 Nexstar Media, Inc. All rights reserved.

Help us improve.