Researchers reviewed eight ocean-focused climate interventions and found that while some approaches can increase carbon uptake or briefly cool the planet, none are without ecological risk. Biological methods like iron fertilization and seaweed cultivation can sequester carbon but may re-emit it and disrupt nutrient flows, harming fisheries. Chemical options such as alkalinity enhancement — particularly electrochemical approaches — may pose lower direct biological risk but carry disposal and trace-contaminant uncertainties. The authors call for transparent, urgent research and careful governance before any large-scale deployment.

How Ocean Geoengineering Could Reshape Marine Life — A New Risk Assessment

Climate change is intensifying heat waves, raising sea levels and transforming ocean conditions. Even if nations meet current emissions pledges, warming is likely to exceed what many marine ecosystems can safely tolerate. That reality has driven scientists, governments and startups to explore ways to remove atmospheric carbon dioxide or temporarily cool the planet — but these interventions could have profound, sometimes unexpected, effects on the ocean, Earth’s largest carbon sink.

What We Reviewed

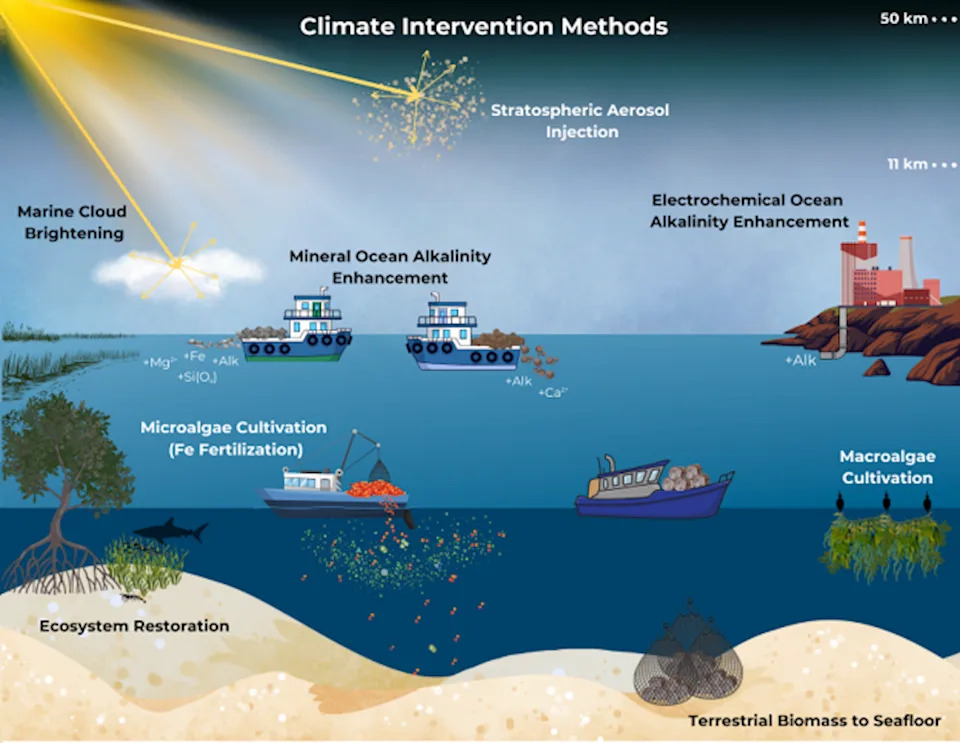

Our research team reviewed eight ocean-focused climate interventions to evaluate their potential benefits and ecological risks. These approaches fall into two broad categories: Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR), which aims to remove CO2 from the atmosphere, and Solar Radiation Modification (SRM), which seeks to reduce incoming solar energy to cool the planet temporarily.

Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR)

CDR methods alter ocean biology or chemistry to increase the ocean’s natural uptake and storage of carbon. Major approaches include:

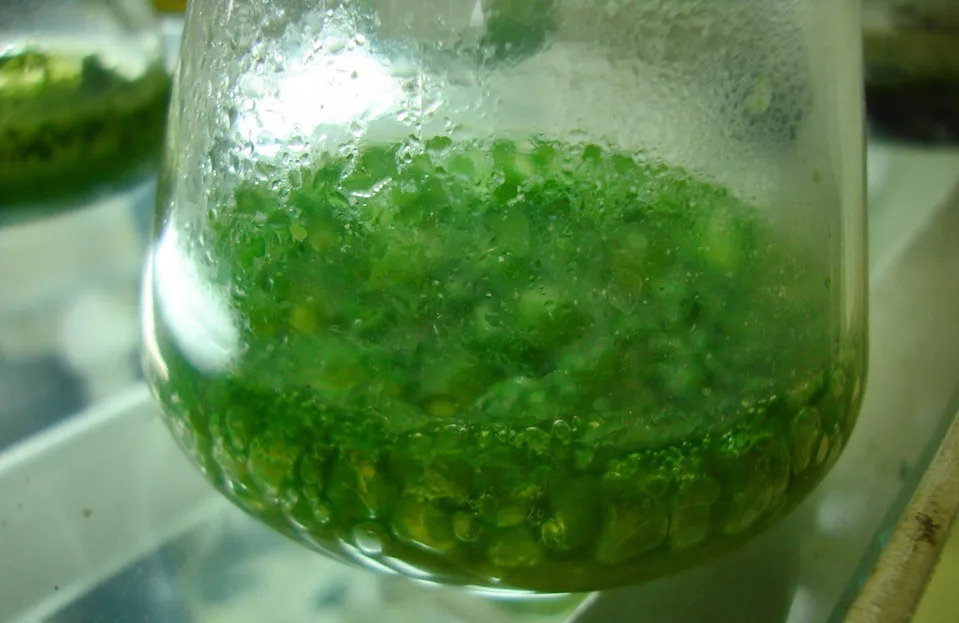

- Biological Methods — e.g., iron fertilization and seaweed cultivation, which stimulate photosynthesis so algae or plants capture more CO2. Some carbon can be stored long-term, but much may return to the atmosphere when biomass decomposes.

- Anoxic Storage of Terrestrial Biomass — sinking land-grown plants into deep, low-oxygen waters where decomposition is slower.

- Ocean Alkalinity Enhancement (OAE) — adding alkaline minerals (pulverized carbonate or silicate rocks like limestone or basalt) or producing alkaline compounds electrochemically to convert dissolved CO2 into less reactive forms and increase ocean uptake.

- Electrochemical OAE — uses electricity to split seawater into an alkaline stream and an acidic stream; the alkaline product has relatively simple chemistry and limited direct biological effects but requires safe handling of acidic by-products.

Solar Radiation Modification (SRM)

SRM does not remove CO2. Instead, it seeks to cool the planet quickly — for example, by brightening clouds or injecting reflective particles into the atmosphere — mimicking the temporary cooling after large volcanic eruptions. SRM could reduce heat extremes and coral bleaching fast, but it only masks warming while CO2 continues to accumulate.

Shared Risks and Ecological Concerns

Each method carries distinct benefits and hazards. Key risks to marine ecosystems include:

- Ocean Acidification: CO2 dissolving in seawater increases acidity, which weakens shell-forming organisms and harms corals and plankton. How an intervention affects acidification depends on where CO2 is taken up and where biomass decays.

- Nutrient Redistribution: Biological fertilization can boost surface productivity locally but may suffocate deeper waters or deplete nutrients that currents supply to distant fisheries, disrupting food webs.

- Trace Contaminants: Some mineral alkalinity sources (for example, certain basalts) and manufactured compounds can introduce trace metals or other contaminants not currently represented in many models.

- Food-Web Reorganization: Shifts in acidification and nutrients will favor some phytoplankton species over others, cascading up the food chain and potentially altering fisheries relied on by millions.

- Operational and Disposal Challenges: Electrochemical methods generate an acidic stream that must be neutralized or disposed of safely; large-scale mining and transport of minerals have additional environmental footprints.

Modeling, Knowledge Gaps and the Need for Careful Research

Scientists commonly use computer models to explore outcomes before ocean-scale experiments. However, models are limited by gaps in empirical data: many biological responses, trace-metal effects, and ecosystem reorganizations around new habitats (such as seaweed farms) are not yet well represented. Carefully designed laboratory studies and small, monitored field trials are necessary to improve model realism and reduce uncertainty.

Governance, Commercial Pressure and Why Research Should Continue

Some argue the risks are too high and that research should stop to avoid distraction from emissions reductions. We disagree. Private companies are already commercializing marine CDR and selling carbon credits, and political pressure may drive governments toward rapid deployment before risks are fully understood. Transparent, independent research is urgent: to rule out harmful options, verify promising approaches, and ensure deployments stop if unacceptable impacts emerge.

Conclusion

No ocean-focused climate intervention is risk-free. Some approaches — notably electrochemical alkalinity enhancement and carefully sourced carbonate additions — appear to pose lower direct biological risks, but uncertainties remain. Decisions about researching or deploying these technologies should be guided by rigorous science, transparent governance and precaution, not by market pressure or ideology.

Note: These findings summarize a multidisciplinary scientific assessment. Further laboratory experiments, controlled field trials and improved models are essential before considering large-scale ocean interventions.

Help us improve.