A small group of researchers and several private start‑ups are pushing a controversial idea: intentionally releasing tiny reflective particles into the atmosphere to reduce incoming sunlight and temporarily cool the planet. Advocates say the approach could buy time while the world cuts greenhouse gas emissions; critics warn it carries environmental risks, governance gaps and the danger of distracting from proven mitigation.

Start-ups, academics, and governments are increasingly interested in using technology to block out sunlight as a way to battle the climate crisis, though increased criticism accompanied this new momentum (Make Sunsets)

What Is Solar Geoengineering?

Solar geoengineering or solar radiation modification seeks to mimic the cooling effect that follows some large volcanic eruptions by scattering sunlight back to space. The concept dates to the 1960s, but only in the last two decades have small field tests and private experiments begun.

Stardust Solutions, a secretive start-up founded by Israeli scientists Yanai Yedvab (right) and Amyad Spector (left), proposes to use a novel (and still undisclosed) particle to help cool the Earth (Roby Yahav, Stardust)

Who Is Working On This—and Why

In October, Stardust Solutions announced it had raised $60 million to advance a technology it says will deploy a non‑sulfate reflective particle into the stratosphere to reduce how much solar energy reaches Earth’s surface. The company, founded in 2023 by Yanai Yedvab, Amyad Spector and Eli Waxman, says its particle is patent‑pending, non‑sulfate (to avoid the known harms of sulfate aerosols) and currently tested in controlled laboratories. Stardust intends to pursue limited, contained outdoor experiments and publish peer‑reviewed results before any operational deployment.

Blocking some of the sun’s radiation from hitting the Earth will not stop the climate crisis — only reducing the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere will do that in the long run — but it could reduce global temperatures and buy the world more time to implement solutions, according to backers

Stardust’s founders argue the climate emergency requires exploring all credible options so governments have validated tools available if a rapid intervention becomes necessary. They compare the effort to past international cooperation on the ozone hole, saying preparedness could prevent rushed, risky choices later.

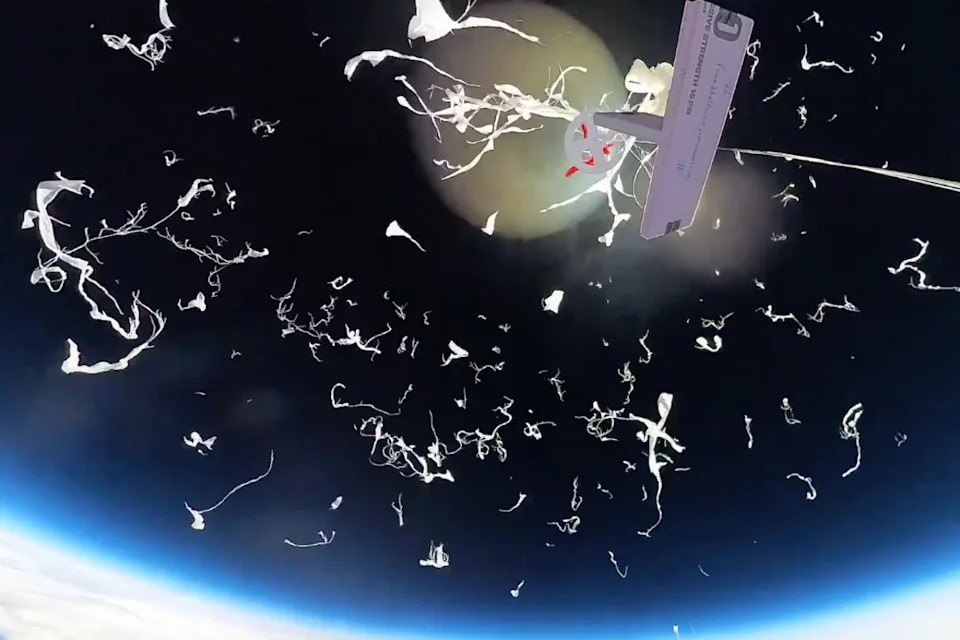

Make Sunsets, a California start-up, is already releasing balloons filled with sun-blocking particles into the atmosphere, though its efforts have attracted criticism from U.S. and Mexican regulators (Make Sunsets)

Private Actors Are Already Testing

Not all efforts are confined to labs. Make Sunsets, a smaller U.S. start‑up founded in 2022, has lofted weather balloons carrying sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere. The company says each gram of sulfur dioxide offsets roughly the warming effect of one metric ton of CO2 for a year and sells so‑called "cooling credits." Make Sunsets reports 213 balloon launches and 207,007 cooling credits issued. Its founders say they comply with applicable U.S. reporting rules and notify relevant agencies.

Geoengineering companies like Make Sunsets hope to mimic the climate-cooling effects of volcanic eruptions like Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines in June 1991, whose plume of aerosols is thought to have temporarily lowered global temperatures by half a degree Celsius (Getty Images)

Those activities have drawn scrutiny. Mexico accused Make Sunsets of launching without local permission. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency requested more information, and scientific advisers have warned against monetizing solar geoengineering without robust review.

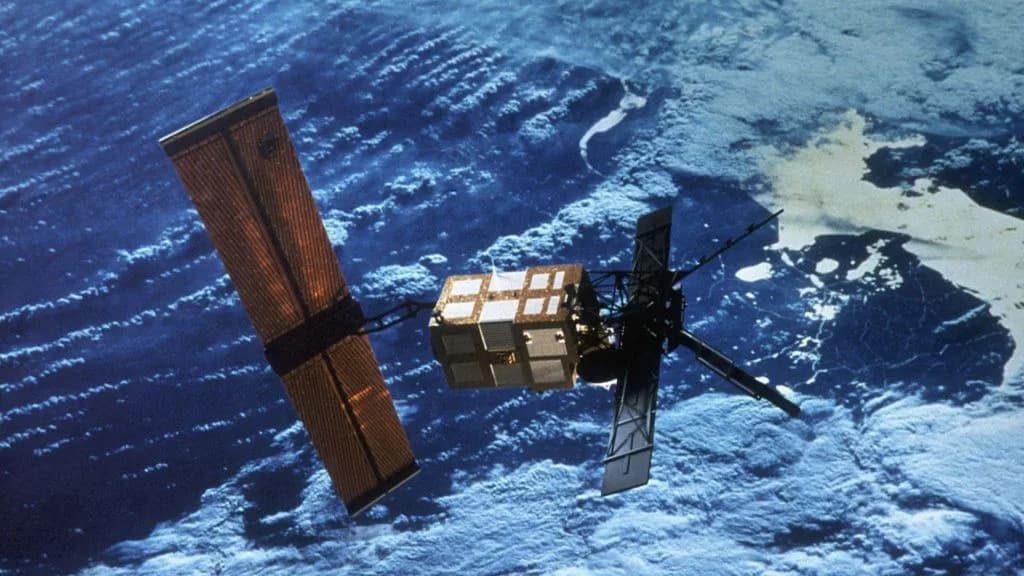

There are no binding global agreements on solar geoengineering, though experts warn coordinated global planning and monitoring should be a part of any proposed solution (Copyright 2018 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.)

Public Reaction, Regulation And Research Funding

Public opposition has already halted several proposed field tests. Indigenous communities and local residents have objected to releases they say violate cultural values or occurred without meaningful consultation. At least 19 U.S. states have seen bills to ban parts of geoengineering, and Tennessee, Louisiana and Florida have existing weather‑modification restrictions that reflect broader unease and conspiracy narratives about "chemtrails."

Beyond using particles, some scientists have proposed deploying huge mirrors to space to reflect away some of the sun’s light before it hits the Earth (SPL)

Governments and public agencies are also funding research. The UK’s Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA) launched a geoengineering program backed by roughly $75 million for controlled, small‑scale outdoor experiments and academic studies. Proposed lines of inquiry include cloud brightening, Arctic ice stabilization and other targeted interventions. More speculative proposals—such as tethering a reflective structure to an asteroid—have been floated in academic settings, demonstrating the breadth of thinking in the field.

Critics of geoengineering say that beyond just being insufficient to stop the climate crisis, the technology is untested, could have adverse climate impacts, and is being deployed in a world without the legal structures or international cooperation to guide such a novel strategy (UK MOD © Crown copyright 2024)

Scientific And Ethical Concerns

Many scientists and advocacy groups remain skeptical. Key risks raised include:

Private companies are the wrong institutions to carry out geoengineering, according to critics, because they are drive by a profit-motive in addition to concerns for the public wellbeing (iStock/ Getty Images)

• Ozone depletion, acid deposition and other chemical side effects from some aerosols;

• Regional shifts in precipitation patterns and extreme weather intensity;

• A "termination shock" if geoengineering is abruptly halted—rapid warming could follow if temperatures were artificially suppressed for years and then the measure stopped;

• The risk that research and investment divert political will and funding away from rapid decarbonization.

Critics argue private companies are ill‑suited to lead such interventions because profit motives could bias deployment decisions or reduce transparency and accountability. Noted climate engineer David Keith and others have publicly questioned rapid claims about new, supposedly neutral particles that could avoid environmental harms in a short span of development.

Where We Stand

Solar geoengineering remains a contested, high‑stakes field. Some researchers argue limited, transparent, internationally coordinated research is warranted to understand risks and options. Others say the focus must remain on cutting emissions, the only proven way to address the root cause of climate change.

As experiments continue and private actors increasingly test technologies outside traditional academic settings, urgent questions persist: Who decides whether to test or deploy these techniques? How are risks assessed and compensated? What governance structures will guarantee transparency, independent review and global accountability?

Bottom line: Solar geoengineering could buy time if it works as intended, but it carries significant environmental and political risks. Robust, inclusive governance and strong scientific validation are essential before any wide‑scale deployment is considered.