Leaders and researchers are pushing to reduce ultraprocessed foods in school meals and expand scratch cooking—preparing meals from whole, minimally processed ingredients—to improve child health. Major barriers include outdated kitchen infrastructure, staffing and training gaps, procurement rules, and tight federal reimbursement rates (about $4.60 per free lunch). Experts recommend higher reimbursements, capital and workforce investments, local purchasing support, and gradual transitions to scale scratch cooking while building student acceptance.

Getting Ultraprocessed Food Out of School Meals: What It Takes To Start Scratch Cooking

In April, U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. put school food at the center of his Make American Healthy Again agenda, promising “major, dramatic changes” to the federal school nutrition programs that serve nearly 30 million students each year. Kennedy warned that roughly 70% of foods served in those programs are ultraprocessed and urged urgent action to improve childhood nutrition.

Policymakers, researchers and practitioners are now debating what it would take for districts to shift from packaged, industrially produced items to scratch cooking — preparing meals from whole, raw or minimally processed ingredients — while meeting federal requirements and staying within tight budgets.

What Are Ultraprocessed Foods and Why Does It Matter?

Ultraprocessed foods are generally industrially manufactured, ready-to-eat or heat products that often contain high levels of added sugar, salt, refined fats and additives. Examples include chips, sodas, frozen packaged meals and many convenience breakfast items. Global and U.S. consumption has risen rapidly: a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analysis found children and teens get more than 60% of their daily calories from ultraprocessed products.

Mounting research links high intake of ultraprocessed foods to worse health outcomes. A three-part series in The Lancet concluded that increased consumption of ultraprocessed foods is a key driver of rising diet-related chronic disease and recommended that governments restrict ultraprocessed foods in school meals.

Why Federal Nutrition Rules Alone Aren't Enough

Federal efforts have focused on stricter nutrient standards (limits on added sugars, sodium and saturated fat), but manufacturers often reformulate products to meet new thresholds without reducing overall ultraprocessing. Faced with constrained budgets and limited staff capacity, many school nutrition programs still rely on ready-made items such as frozen pizzas, prepackaged sandwiches and packaged breakfast pastries.

What It Takes To Scratch Cook

School districts that want to increase scratch-cooked meals must address four practical constraints: kitchen equipment, trained staff, ingredient procurement, and meal planning that complies with USDA meal patterns.

Equipment

Many kitchens lack essential infrastructure — coolers, freezers, running water, prep space and updated electrical systems. Replacing or renovating equipment is costly. School nutrition programs operate as largely self-sustaining nonprofit enterprises, and federal reimbursements (about $4.60 per free lunch) must cover food, labor, supplies, equipment and overhead. That often leaves little capital for major upgrades. Even when districts buy equipment, older buildings can lack the power or utilities to use it effectively.

Staffing and Training

Recruitment and retention are major challenges. In a 2024 School Nutrition Association (SNA) survey, nearly 89% of directors reported staffing problems and the vacancy rate was 8.7%. Scratch cooking demands culinary skills, food-safety knowledge and familiarity with equipment. Many employees are not paid or scheduled to attend training, which slows skill development and makes transitions harder.

"It’s about valuing food — valuing what they contribute to the school day and to the students’ life. We don’t value them, and that’s why they’re many times the lowest paid," said Dr. Katie Wilson, executive director of the Urban School Food Alliance.

Ingredients and Procurement

Moving to whole ingredients often requires new vendor relationships and new contracting practices. Schools that receive federal funds must follow procurement rules that vary by purchase size and sometimes by state or locality; more restrictive local thresholds override federal rules. Inconsistent interpretations of procurement rules make local sourcing difficult and slow to implement.

Menu Planning and Federal Meal Patterns

The USDA enforces meal patterns that specify required meal components (for example, vegetable cup equivalents) and place limits on calories, added sugar, sodium and saturated fat. Scratch recipes can meet these standards, but they require more planning and create greater variability than prepackaged items, which can be counted reliably. Small measurement deviations can disqualify a scratch item from counting as a reimbursable component, creating practical barriers for districts.

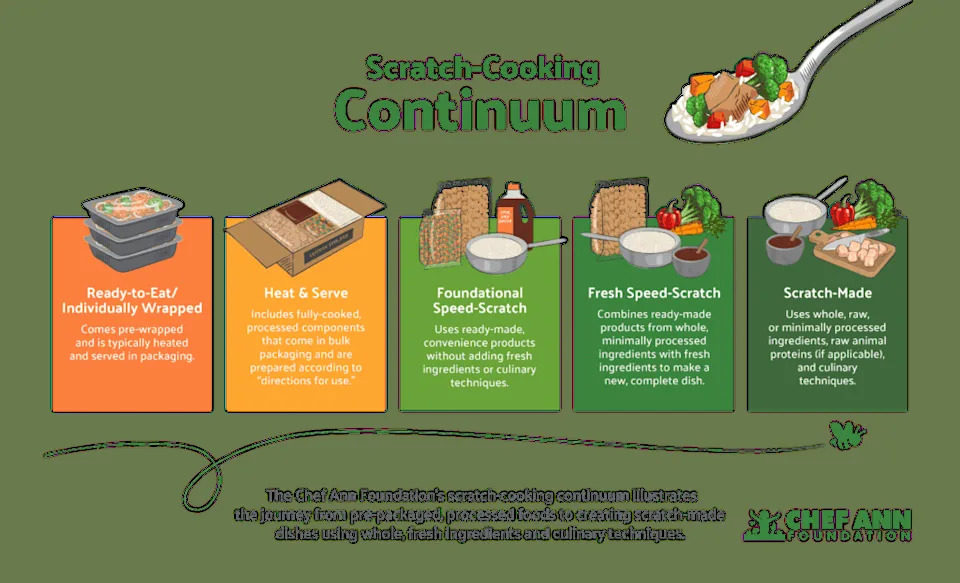

Adaptive Challenges: Culture, Buy-In and Student Tastes

Shifting from ultraprocessed items to scratch cooking is not just technical; it requires changing mindsets and building culture. Leadership commitment, staff buy-in and community engagement are essential. The Chef Ann Foundation recommends a gradual continuum from ready-to-eat to fully scratch-made meals so districts can build capacity step by step.

Practices that help acceptance include hands-on staff training, menu committees that include frontline staff, taste tests for students, and clear communication with families about ingredients and local sourcing. Even with these strategies, experts note a transition period is often needed because ultraprocessed foods can shape strong taste preferences.

The Financial Equation

Scratch cooking is often perceived as more expensive, but it does not always increase per-serving costs. Up-front capital costs for equipment are the biggest barrier; however, strategic menu planning and bulk procurement can lower ongoing costs. For example, Yadkin County and Elkin City schools report a scratch-made spaghetti sauce costing about $0.95 per serving versus $1.10 for a pre-made product. Evaluations of districts in the Chef Ann Foundation’s Get Schools Cooking program showed improved financial health after transitioning to more scratch cooking.

Still, many directors feel squeezed by rising food and labor costs and static federal reimbursements. Operating under constrained budgets, complex regulations and thin staffing can feel like "building a Jenga tower and hoping it doesn’t fall," according to one director.

Policy Solutions and Investment Priorities

Experts and school leaders point to several priorities to enable scale-up of scratch cooking:

- Higher Meal Reimbursements: Federal reimbursements (about $4.60 per free lunch and $2.46 per free breakfast) have not kept pace with costs. The Healthy Meals Help Kids Learn Act of 2025, introduced in Congress, would permanently raise reimbursements by $0.45 per lunch and $0.28 per breakfast.

- Capital Funding For Kitchens: Grants or state investments can fund equipment and retrofits. California has committed more than $700 million from the general fund for kitchen infrastructure and training to expand scratch-made options.

- Workforce Development: Registered apprenticeship and pre-apprenticeship programs (such as those created by the Chef Ann Foundation) can build culinary skills for school food workers and create career pathways.

- Support For Local Purchasing: Funds to buy local foods help districts source fresh ingredients and support regional farmers. The cancellation of $660 million for the USDA Local Food for Schools Cooperative Agreement Program in March 2025 removed a major funding stream that helped states buy local foods for schools.

- Universal Free Meals: Universal free-meal programs increase participation and stable reimbursements, giving programs scale to invest in scratch cooking. Nine states have permanent universal free school meal laws.

Conclusion

Reducing ultraprocessed food in school meals and expanding scratch cooking is feasible but requires coordinated investments in equipment, workforce, procurement reform and reimbursement policy. Districts that have invested strategically report both stronger community support and improved financial outcomes. Advocates say the payoff—healthier children and a stronger connection between schools and local food systems—is worth the effort.

This article first appeared on EdNC and is republished under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.