Researchers detected Yersinia pestis DNA in a 4,000-year-old domesticated sheep from Arkaim, Russia, providing the first robust evidence of the Late Neolithic Bronze Age (LNBA) plague lineage in a non-human animal. The ancient strain lacked genetic changes that later enabled flea transmission, suggesting alternative routes or reservoirs helped spread the pathogen across the Eurasian steppe. The discovery—published in Cell—links livestock mobility and human expansion to prehistoric disease dispersal but cautions that more genomes are needed to identify the reservoir and full ecology of this early plague lineage.

4,000-Year-Old Sheep DNA Links Livestock To The World's Earliest Plague

A strain of Yersinia pestis—the bacterium that causes plague—has been identified in the DNA of a domesticated sheep buried at Arkaim, a Bronze Age settlement in the Southern Ural Mountains. The animal lived about 4,000 years ago and carried a member of the Late Neolithic Bronze Age (LNBA) lineage of the pathogen. This lineage predates the medieval Black Death by millennia and lacked the genetic adaptations later required for flea-mediated transmission.

What Researchers Did

As part of a large archaeogenetic project tracking how livestock accompanied human migrations from the Fertile Crescent across Eurasia, scientists sequenced highly degraded DNA from Bronze Age cattle, goats and sheep. Ancient animal DNA is typically fragmented and contaminated by microbes, but that "genetic soup" can also reveal pathogens that once infected herds and their handlers.

Key Discovery

The team detected Yersinia pestis DNA in a tooth from a sheep found at Arkaim. The recovered genome belongs to the LNBA lineage, which lacked the later flea-transmission adaptations. Because that early form of the bacterium could not spread efficiently via fleas, archaeologists have debated how it traveled long distances and infected people across wide areas of Eurasia.

"It had to be more than people moving. Our plague sheep gave us a breakthrough," says University of Arkansas archaeologist Taylor Hermes, a lead author on the study.

Implications

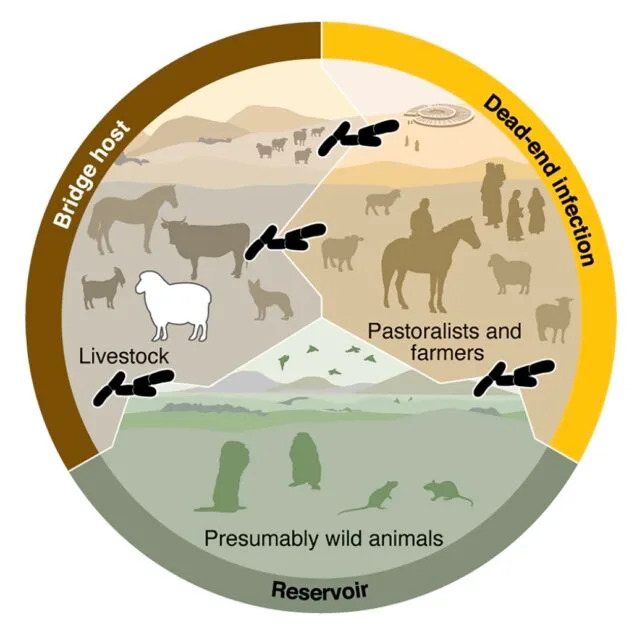

This is the first robust detection of the LNBA Y. pestis lineage in a non-human animal. The finding suggests domestic sheep—moving across the vast Eurasian steppe—may have acquired the bacterium from a wild reservoir (for example, steppe rodents or possibly migratory birds) and then helped disperse it between flocks and to humans. The Arkaim site is associated with the Sintashta culture, a mobile, horse-riding Bronze Age society whose expanding herds and increased territorial range could have amplified contacts with wildlife reservoirs.

Challenges And Cautions

Recovering pathogen genomes from ancient faunal remains is difficult: animal bones are often poorly preserved, commonly represent consumption waste (which may have been cooked), and assemblages are biased toward apparently healthy specimens. As the authors — including biologist Ian Light-Maka of the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology — note, a single infected carcass that survives to be found and sequenced is rare. Previous claims of Y. pestis in ancient animals (a medieval rat and a Neolithic dog) produced highly fragmented DNA that did not allow robust genomes; the Arkaim sheep provides stronger evidence.

Conclusions

Although this discovery strengthens the hypothesis that livestock helped move the LNBA plague across large distances, it does not yet identify the natural reservoir or fully reconstruct the pathogen's ecology. The study, published in the journal Cell, highlights the dynamic interplay among people, their animals, and wildlife in prehistoric disease spread and underscores the need for more ancient genomes to clarify transmission pathways.