Stone tools are rocks chosen or intentionally modified by hominins; they leave consistent physical traces. Flintknapping—the controlled removal of flakes from a core—produces diagnostic features such as flake scars and a bulb of percussion. Material properties like conchoidal fracture (seen in obsidian) make predictable flakes possible, and archaeological context (many similar flakes or exotic raw materials) helps confirm human manufacture.

Stone Tool or Just a Rock? How Archaeologists Tell the Difference

Have you ever stood in a museum’s human origins gallery, peered into a case of stones labeled “stone tools,” and wondered how curators know those objects aren’t just ordinary rocks? At first glance the distinction can seem impossible. As an experimental archaeologist who has spent more than a decade making and studying stone tools, I can say there are consistent, diagnostic traces that reveal deliberate human—or hominin—modification.

What Is Flintknapping?

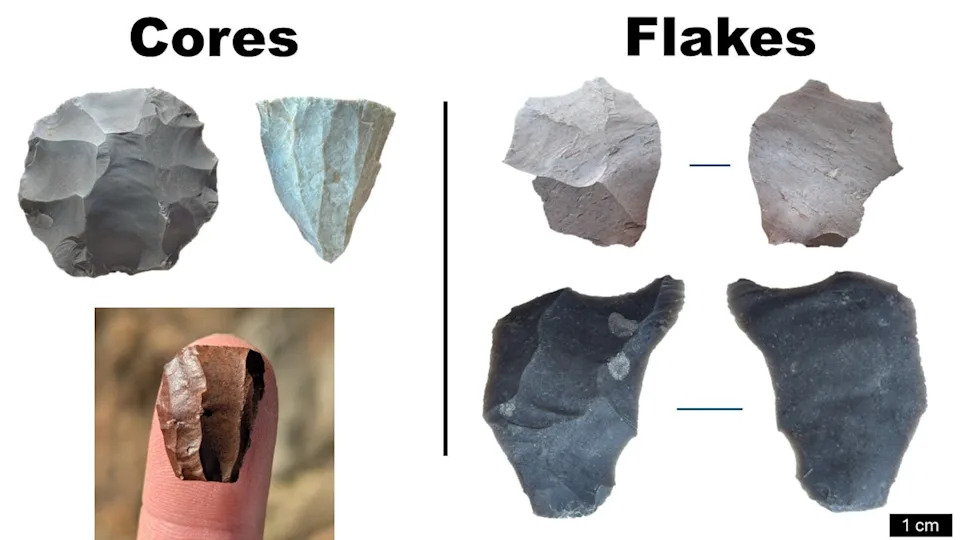

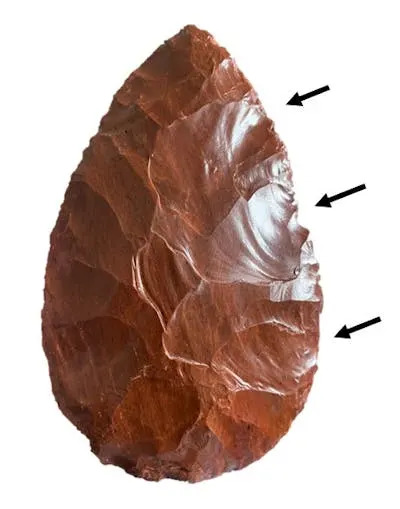

Flintknapping is the intentional shaping of stone by removing flakes from a larger piece (a core) using controlled force and angle. Makers use percussion (striking with a hammerstone or antler billet) or pressure to detach flakes, and the removed flakes themselves can be useful as cutting edges or further shaped into implements such as hand axes.

Why Some Rocks Work Better Than Others

Not every rock is suitable for predictable flaking. The best materials exhibit conchoidal fracture—a smooth, curved break with ripple-like waves, similar to how glass shatters. Volcanic glass (obsidian) is a classic example. Knowing how a material breaks lets an experienced knapper predict flake size and shape.

Diagnostic Features of Worked Stone

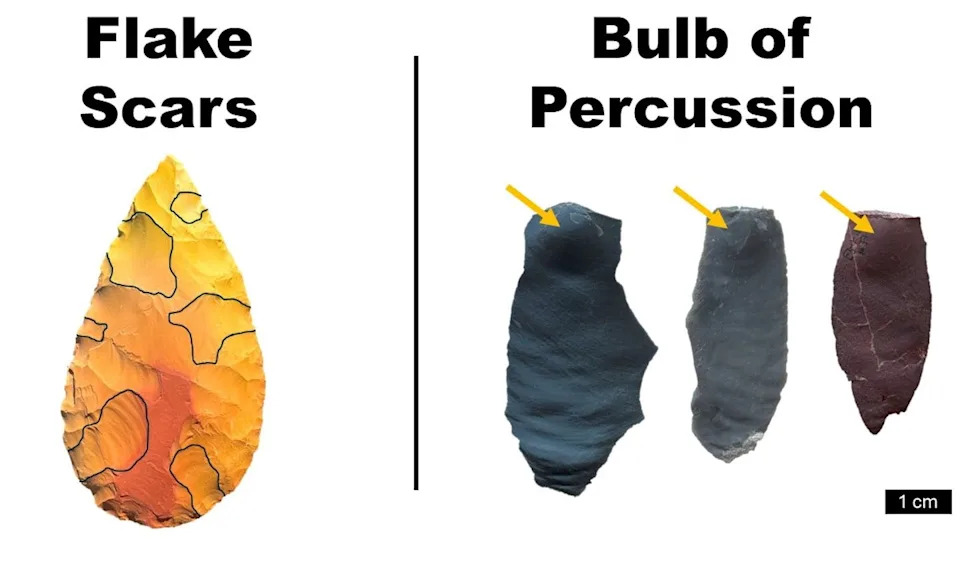

Archaeologists distinguish worked stone from natural fragments by looking for features produced during controlled fracture. Key traces include:

- Flake Scars: Negative removals on a core or on larger flakes. Repeated, consistently oriented scars signal deliberate reduction rather than random breakage.

- Bulb of Percussion: A rounded bulge on the flake just below the former striking platform caused by force concentration when the flake detached. Producing a bulb requires hitting a platform at a particular angle with sufficient force.

- Striking Platform: The prepared edge on the core where force was applied; when removed, it remains visible on the detached flake.

Although natural processes can produce sharp fragments (sometimes called naturaliths), a single sharp flake is less convincing than a pattern of flakes showing the same diagnostic features.

Context Matters

Archaeologists place great weight on context. A concentration of flakes with consistent attributes—often made from the same raw material—can indicate a knapping workshop. Conversely, a single object made from a non-local stone might indicate long-distance transport or trade. Questions to ask include: Are many similar flakes found together? Does the material match nearby geology, or is it exotic?

Learning By Doing

The best way to appreciate these clues is to try flintknapping. I have taught more than 100 students of all ages, and almost everyone is surprised at how difficult controlled flaking is. Hands-on practice reveals the choices and constraints our hominin ancestors faced when they first solved the technological challenge of producing sharp edges from raw rock.

Takeaway: Stone tools first appear in the archaeological record around 3.3 million years ago. Look for patterned flake scars, bulbs of percussion, predictable fracture surfaces, and contextual concentration of material to distinguish deliberate manufacture from natural fragments.

Article originally written by John K. Murray, Arizona State University, and republished from The Conversation.

Help us improve.