Israeli scientists have sped up natural carbonate weathering—normally a millennia‑long sink—so it locks CO₂ into dissolved bicarbonate within hours using seawater and common carbonate rocks in a transparent reactor. The team found CO₂‑to‑seawater ratio, gentle gas recycling, and rock grain size are key controls, and identified dolomite as especially promising because it avoids forming secondary carbonates. The lab system currently converts about 20% of introduced CO₂ to dissolved carbon; further engineering is needed to scale and optimize the approach for power plants and heavy industries.

Israeli Team Compresses Millennia‑Long Carbonate Weathering Into Hours — A Scalable Nature‑Based CO₂ Capture

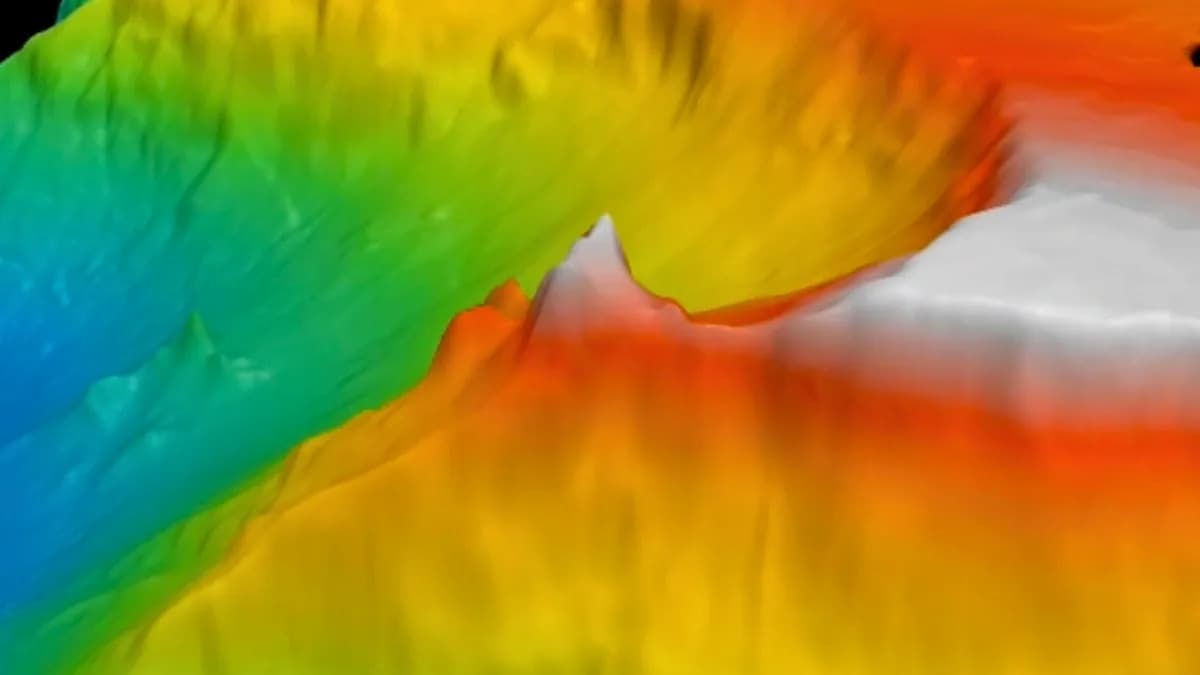

Israeli researchers have developed a laboratory method that dramatically speeds up a natural carbon removal process so that it locks carbon dioxide into dissolved bicarbonate in hours instead of millennia. Using inexpensive, abundant materials — seawater and common carbonate rocks such as limestone and dolomite — the team created a transparent reactor that lets them observe, measure and tune the reactions that normally occur very slowly in the geologic cycle.

The experiment: Researchers from Hebrew University (Noga Moran and Yonaton Goldsmith) and the Open University (Eyal Wargaft) ran CO₂‑saturated seawater through packed beds of carbonate rock inside a transparent flow reactor. This setup mimics natural carbonate weathering, which in the environment occurs when mildly acidic water reacts with carbonate minerals to produce dissolved bicarbonate that rivers carry to the ocean.

Key findings: The team identified several controllable factors that strongly influence conversion efficiency: the CO₂‑to‑seawater ratio, modest recycling of the gas stream to increase contact time, and the grain size of the rock, which affects both reaction rate and total dissolved carbon. Under current laboratory conditions the system converts roughly 20% of introduced CO₂ into dissolved bicarbonate, with substantial opportunity for engineering improvements.

“The goal was to understand what’s really happening when carbonate rocks encounter high levels of carbon dioxide,” said Noga Moran. “Once we identified the conditions that allowed the process to work efficiently, we could measure and tune a natural process that normally takes millennia.”

Why dolomite matters: Dolomite performed particularly well because it is less prone to forming secondary carbonate minerals that could later re‑release CO₂. That lowers the risk that captured carbon would return to the atmosphere during subsequent mineral transformations.

Potential applications: The authors propose that similar reactors could be deployed at power plants and heavy‑emitting industrial sites — such as cement, steel and chemical plants — to intercept a portion of process emissions. Because the method relies on broadly available materials (carbonate rock and seawater) it could offer a relatively low‑cost, nature‑based complement to existing carbon‑capture technologies. However, the approach remains at laboratory scale and currently captures only about one‑fifth of feed CO₂, so scale‑up and system optimization are needed.

Publication and outlook: The results appear in the peer‑reviewed journal Environmental Science & Technology. The study provides an engineering roadmap for translating natural carbonate weathering into controlled, tunable systems and highlights the next steps: boosting conversion efficiency, testing continuous operation, assessing long‑term stability, and evaluating lifecycle and environmental impacts before field deployment.

Limitations and next steps: The laboratory conversion rate (≈20%) leaves room for improvement. Future work must address reactor design, economic and energy costs of CO₂ handling, potential ecological impacts of discharging bicarbonate‑rich solutions, and integration with existing industrial processes to assess real‑world feasibility.

Help us improve.