Zooplankton blooms—especially dense aggregations of the copepod Calanus finmarchicus—are central to the Gulf of Maine food web and to the feeding behavior of the endangered North Atlantic right whale. Warming waters are pushing these fatty prey northward, replacing them with smaller, less nutritious species. Scientists use satellite mapping of surface copepod concentrations and deep-water monitoring to predict whale movements and to gain early warning of climate-driven ecosystem shifts, improving conservation responses.

Zooplankton Point the Way: Predicting Right Whale Feeding Grounds as the Gulf of Maine Warms

Three years ago, Bigelow Laboratory senior research scientist Karen Stamieszkin watched red plumes pooling beneath the waves of the Gulf of Maine: a large spring bloom of plankton dominated by copepods. "You could see these plumes of this fat, rich copepod population right at the surface," she said. "That is what drives the Gulf of Maine’s iconic fisheries."

Tiny Animals, Big Role

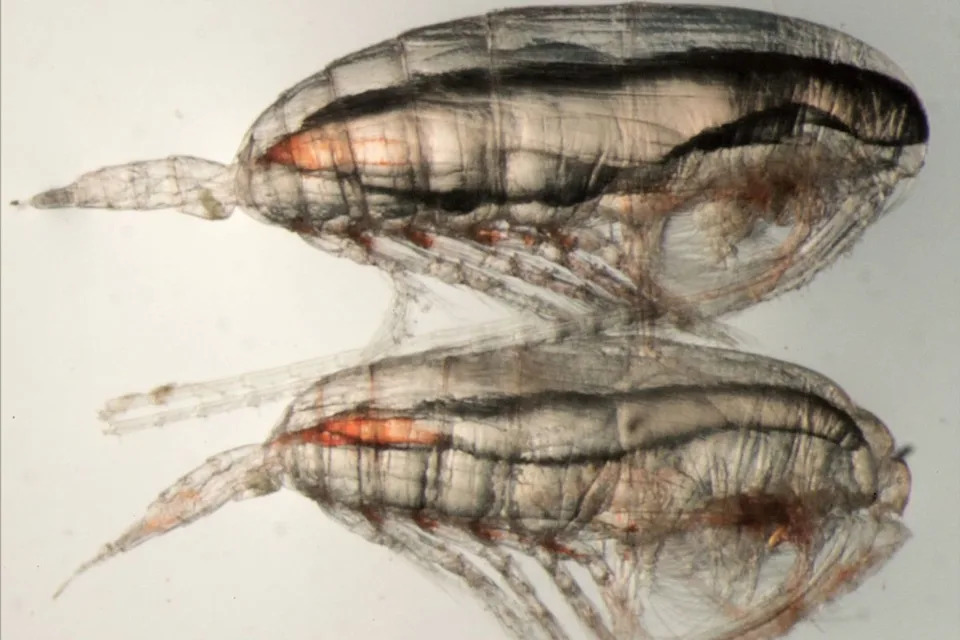

Zooplankton—small, drifting animals such as copepods—graze on phytoplankton and transfer energy up the food chain, sustaining species from herring and cod to tuna. They also play a major role in moving carbon from the ocean surface to depth, helping regulate the global climate.

Food For A Giant: Calanus finmarchicus

One species, Calanus finmarchicus, is especially important in the Gulf of Maine. These fatty copepods are a primary prey item for the endangered North Atlantic right whale, of which scientists estimate roughly 380 individuals remain. As Jérôme Pinti of the Gulf of Maine Research Institute puts it, "Whales go where the food is."

Warming Waters, Shifting Prey

Because the Gulf of Maine is warming rapidly, the distribution of these zooplankton is shifting north into colder waters such as the Gulf of St. Lawrence. In the southern and central Gulf, Calanus is being replaced by smaller, less nutritious zooplankton—changes that alter where and how right whales feed.

Mapping Surface Blooms And Predicting Whale Movements

Researchers at Bigelow and the Gulf of Maine Research Institute combine satellite imagery with surface observations to map where copepods aggregate. Rebekah Shunmugapandi is building models that use these maps to predict where right whales are likely to feed both now and under future warming scenarios. "When the right whale is following something, there's a high chance it should be Calanus, or the food it is trying to eat," she said.

Currents And An Early Warning System

Historically, the cold Labrador Current has delivered subarctic copepods into the Gulf of Maine. During the 2010s, a period of rapid marine warming reduced copepod delivery and changed whale feeding patterns. Nick Record of Bigelow recalls that deep-water measurements, tied to the Labrador Current, signaled the 2010s warming almost two years before surface temperatures reflected the change. "The right whale saw it two years earlier," he said.

"It's warming fast, but there are ups and downs on top of that. So right now, we're in a cold cycle, and probably things will bounce back at some point. It's hard to say when, but we can watch the deep water and get kind of like an early warning of when it's going to flip back." — Nick Record

Conservation Implications

Better predictions of where copepods concentrate can inform dynamic conservation measures—such as temporary speed restrictions or rerouted shipping lanes—to reduce dangerous ship strikes on right whales. Combining satellite data, in-situ sampling, and subsurface monitoring gives managers and researchers tools to anticipate ecosystem shifts and help protect this endangered species.

Bottom line: Tracking zooplankton distribution connects oceanography to on-the-water conservation—revealing where whales will feed and offering early warnings of climate-driven changes in the Gulf of Maine.

Help us improve.