In June 2024 researchers off Baja California captured the first live photographs and a DNA sample of the ginkgo‑toothed beaked whale (Mesoplodon ginkgodens), linking the species to the long‑recorded BW43 43 kHz acoustic signal. The team used a 492‑foot hydrophone array to triangulate clicks and recovered a biopsy sample — nearly lost to an albatross — that confirmed the acoustic ID. The findings show these whales are deep‑diving, year‑round residents of eastern Pacific canyons, and enable targeted conservation to reduce threats from naval sonar and deep‑sea fishing.

Deep-Sea Ghost No More: First Live Photos and DNA Confirm the Ginkgo‑Toothed Beaked Whale

For more than six decades the ginkgo‑toothed beaked whale (Mesoplodon ginkgodens) was known mainly from battered carcasses that washed ashore — a marine mystery described in 1958 but never seen alive by scientists. In June 2024, an international research team working off Baja California, Mexico, captured the first confirmed live photographs and recovered genetic material that linked the species to a long‑recorded, mysterious underwater call.

How the Discovery Happened

Researchers had been tracking a distinctive high‑frequency echolocation click called BW43 for years. The pulse is an upsweep peaking at about 43 kHz; when slowed for human ears, it resembles a fingernail dragged across a plastic comb. Although acousticians knew BW43 came from a beaked whale, they could not assign it to a species — until the 2024 expedition.

Field Methods: Hydrophones, Binoculars, and a Biopsy

A team led by Dr. Elizabeth Henderson deployed a 492‑foot hydrophone cable from the research vessel Pacific Storm to triangulate clicks in near real‑time. When the hydrophones localized BW43, deck observers scanned the horizon with high‑power binoculars for the brief surface appearances these whales make. Seconds after the clicks were recorded, a small group of whales surfaced near the ship. Crew members captured the first live images while a researcher deployed a biopsy dart to collect a skin sample; the hydrophone record confirmed the animals were the source of BW43.

A Close Call With An Albatross

The precious biopsy nearly drifted away when a curious albatross swooped in to peck at the sample. The team improvised by tossing breakfast rolls and shouting to distract the bird long enough to recover the material. DNA analysis later confirmed that BW43 belongs to the ginkgo‑toothed beaked whale, closing a 60‑year identification gap.

Appearance, Biology, and Behavior

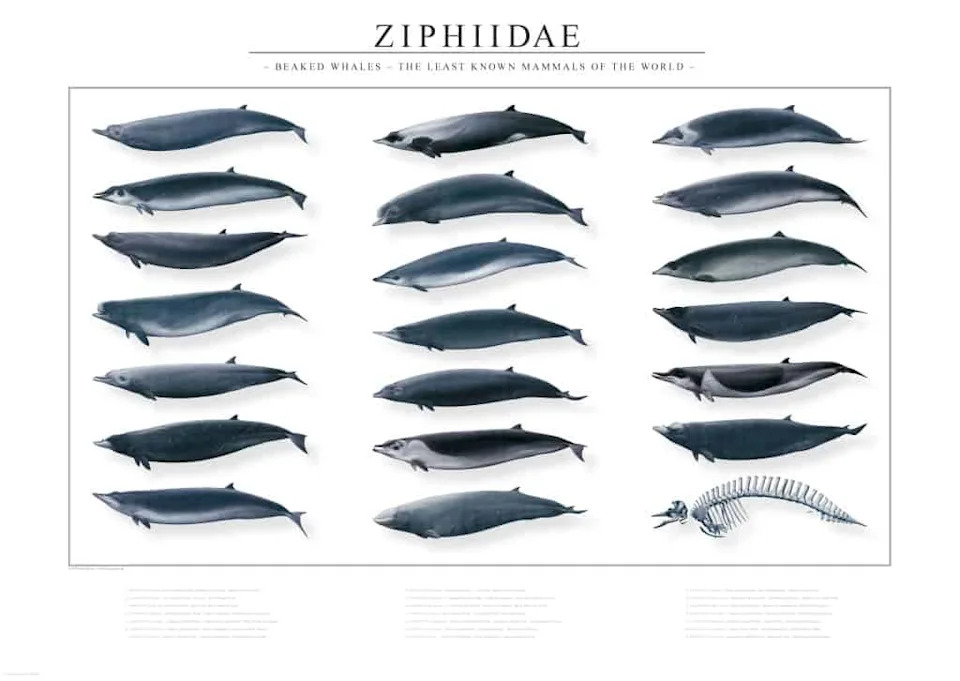

Live photographs revealed striking sexual dimorphism hidden by post‑mortem darkening on stranded carcasses. Adult males reach roughly 17 feet (about 5.2 m) and weigh approximately 4,056 pounds (about 1,840 kg); they are primarily dark blue‑black with white belly blotches and often bear white "rake marks" from male‑to‑male fights. Females are generally a muted mid‑grey with lighter bellies and lack the males’ prominent rake marks. Adult males also have a single pair of erupted, fan‑shaped lower teeth that resemble a ginkgo leaf; females’ teeth remain buried under the gumline.

Despite these teeth, ginkgo‑toothed beaked whales are suction feeders. Powerful throat muscles create a vacuum that pulls deep‑sea fish, squid, and crustaceans into the mouth. These whales are adapted for the ocean’s "midnight zone": they spend roughly 99% of their lives far below the surface, routinely diving beyond 3,000 feet (more than 900 m) with single foraging dives lasting over an hour. Their blubber contains unusually high proportions of wax esters — reported in some studies at very high levels compared with other whales — a trait linked to deep‑water physiology.

Distribution and Conservation Implications

Longstanding finds of carcasses in Japan had left scientists uncertain about the species’ range. However, consistent BW43 recordings off California and northern Baja indicate the ginkgo‑toothed beaked whale is likely a year‑round resident of deep‑water canyons in the eastern Pacific, not merely a rare visitor. Linking BW43 to a confirmed species allows researchers to mine years of acoustic data to map seasonal distributions and hot spots.

That mapping is critical for conservation: beaked whales are among the most acoustically sensitive marine mammals, and Mid‑Frequency Active Sonar (MFAS) from naval exercises can cause displacement, stress, and potentially fatal panic responses that lead to rapid, dangerous ascents. Expanding deep‑sea fishing and increased vessel traffic also raise risks of entanglement and habitat disturbance. With an acoustic signature tied to a species, managers can work with navies, shipping lines, and fisheries to reroute activities away from important habitat and reduce risks without requiring frequent visual encounters.

What This Means

Turning a biological ghost into a photographed, genetically confirmed species transforms how scientists can study and protect a deep‑ocean predator that was once known only from washed‑up remains.

The first live images and DNA confirmation of the ginkgo‑toothed beaked whale mark a major advance in marine biology, opening the door to improved monitoring, habitat mapping, and targeted conservation measures for this secretive deep‑sea species.

Help us improve.