U.S. housing scarcity is driven not only by exclusionary zoning but also by a web of building codes, fire-safety rules and technical standards that disproportionately burden small multifamily construction. Requirements such as sprinkler mandates, two-stair rules, oversized elevator standards and bespoke engineering reviews can make triplexes and fourplexes uneconomical. State-level tweaks and precedents show progress, but broader, more transparent and performance-based reforms are needed to expand safe, affordable housing supply.

How Hidden Building Rules Are Fueling America’s Housing Crisis

For more than a century, U.S. planning and regulatory practices have built up layers of rules that, in practice, discourage apartments and other modest multifamily homes. Policymakers are now discovering that changing zoning is only the first step: a second, less visible set of building codes, safety regulations, utility rules and tax policies often makes small apartment buildings financially infeasible.

Two Problems: Zoning And Code

Zoning frequently prevents denser housing by reserving most residential land for detached single-family homes. But even when cities legalize duplexes, triplexes and fourplexes, model building codes and other rules often treat anything with three or more units as a commercial structure. That classification triggers a jump to more stringent, costlier requirements.

How Technical Rules Block The 'Missing Middle'

Several specific regulations have outsized effects on small multifamily projects:

Sprinkler Mandates

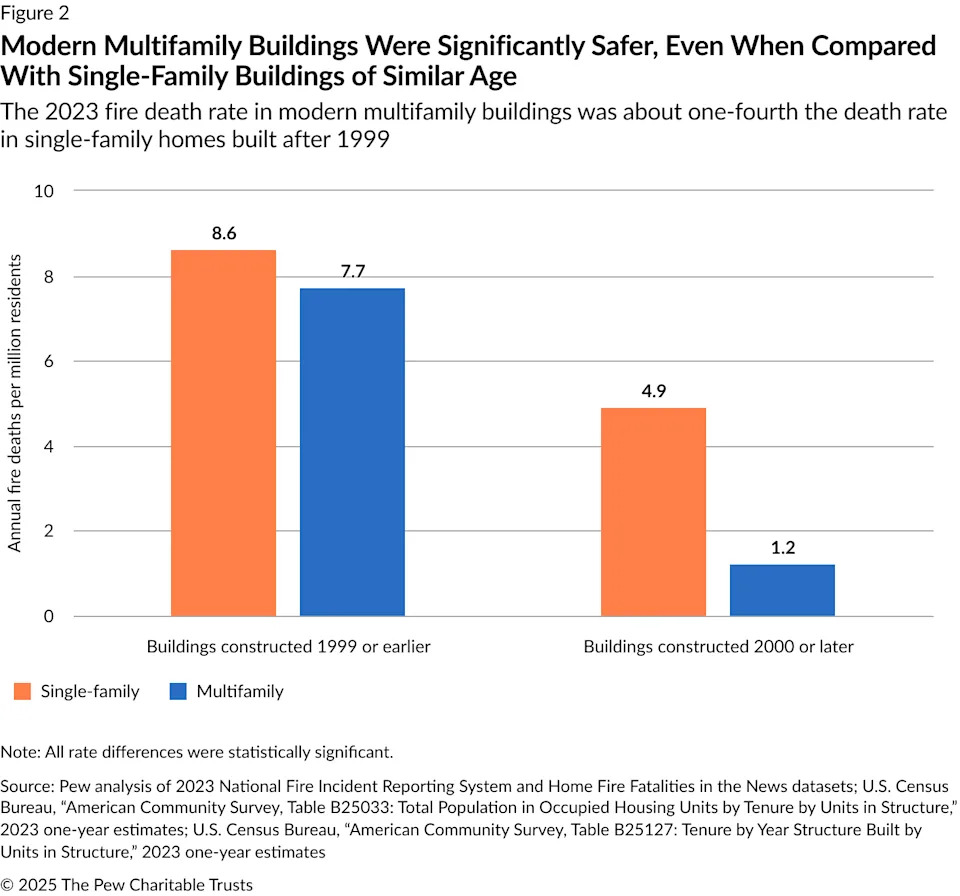

Most jurisdictions require extensive automatic sprinkler systems in buildings classified under the commercial code. While sprinklers save lives in large complexes, their high upfront installation and ongoing maintenance costs can make a small triplex or fourplex economically impossible. Some reformers argue that alternative, evidence-based fire protections could be allowed for modest buildings.

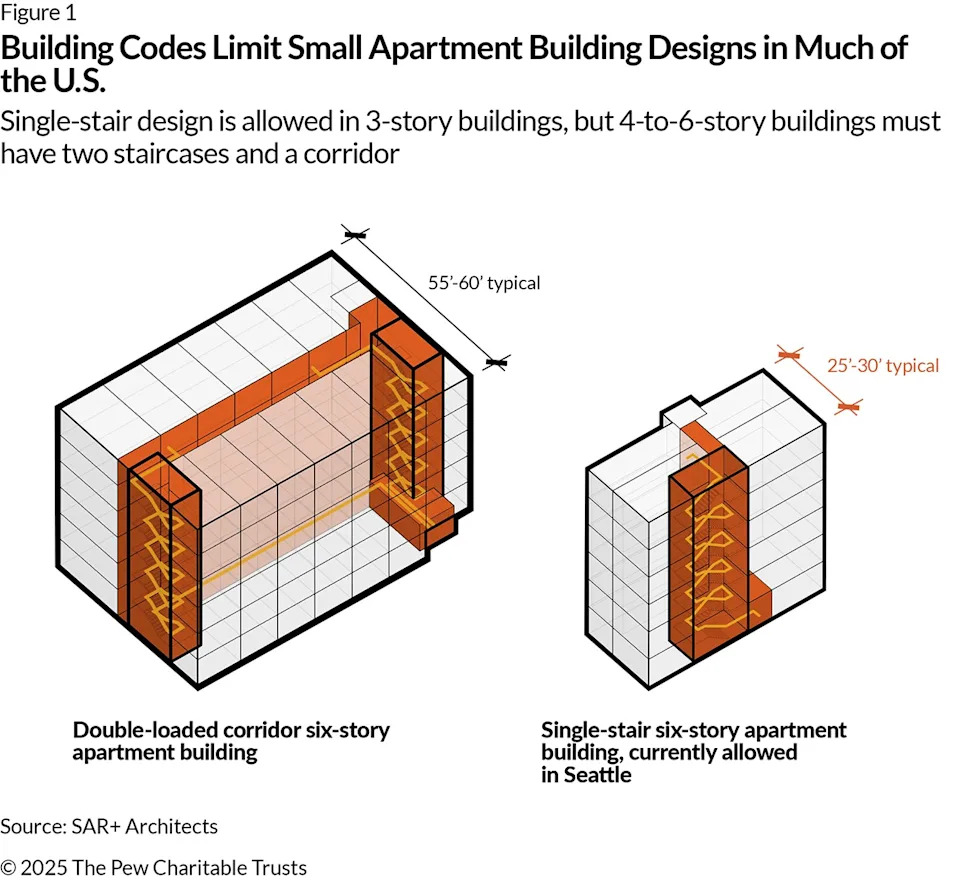

Mandatory Two Staircases

Many new apartment buildings taller than three stories must include two separate staircases. Providing a second stair adds substantial construction cost, reduces usable floor area, and often forces designs toward long central corridors and larger footprints. By contrast, single-stair designs — used safely in many European countries and in some U.S. cities — allow more flexible, family-friendly unit layouts.

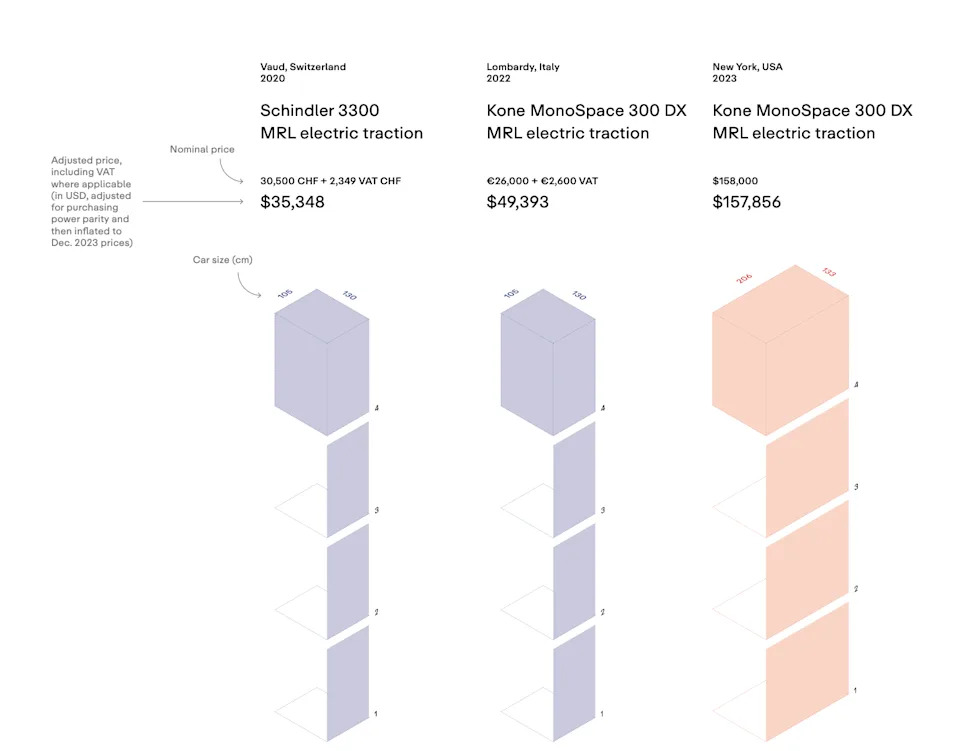

Elevator Requirements

U.S. elevator specifications — such as car sizes sized to fit a seven-foot stretcher and a wheelchair turning radius — make elevators substantially more expensive than their European equivalents. Other factors, including technical standards incompatible with the global market and limits on factory preassembly, further raise costs and delay installation, discouraging mid-rise construction.

Design And Approval Burdens

One- and two-family homes can often be built using prescriptive, pre-approved plans. But in many places, triplexes and fourplexes require custom-engineered plans signed off by licensed architects or engineers, increasing upfront fees and approval time for projects that are often similar in scale to large single-family houses.

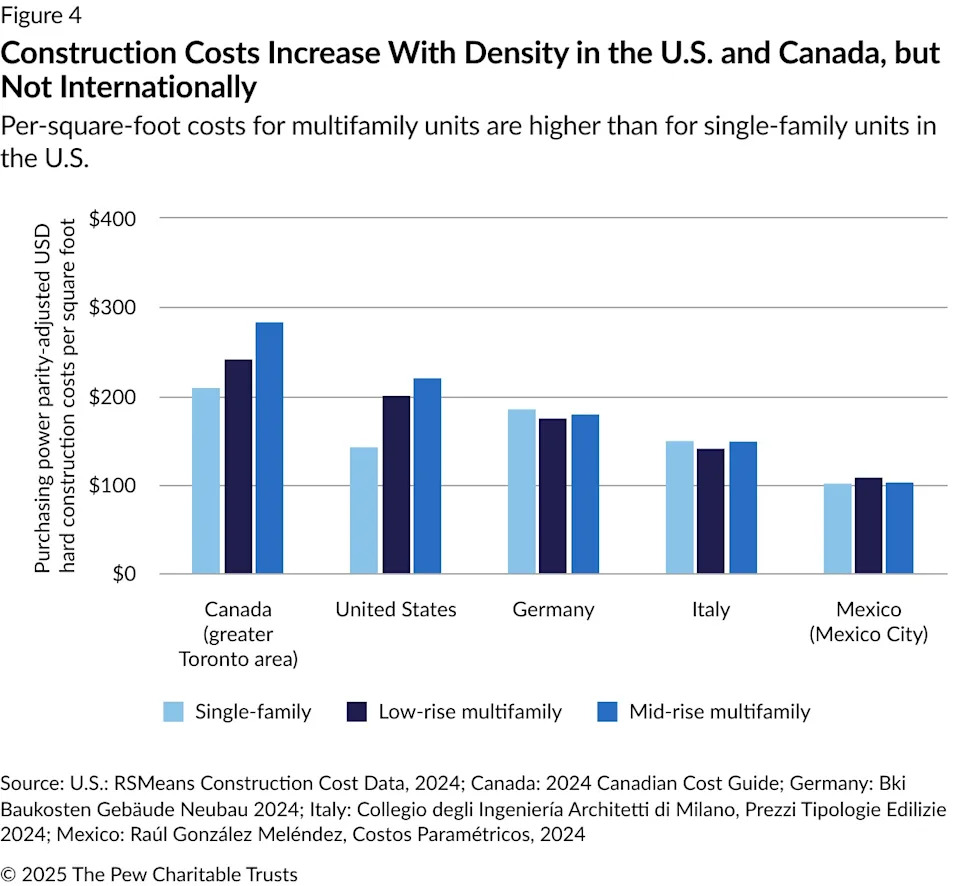

Evidence And Consequences

Reports from Pew Charitable Trusts and the Center for Building in North America find that multifamily construction costs more per square foot in the U.S. than in peer countries — a reversal of expected economies of scale. Research from Purdue University estimates that recent code-driven cost increases can raise the break-even rent for a two-bedroom unit in a new three-story building by roughly $169 to $279 per month.

"Simply allowing a fourplex on paper does not guarantee that one will be built." — John Zeanah, Memphis chief of development and infrastructure

There are real-world policy responses. For example, Tennessee passed a law allowing many small buildings up to four units to forgo sprinklers if they meet two-hour fire-resistant separations between walls, floors and ceilings. Seattle and New York permit certain single-stair configurations, and several states are pursuing narrow code exceptions to encourage missing-middle construction.

Politics, Process, And Reform

Model codes in the U.S. are drawn largely from documents created by the International Code Council (ICC), a private organization whose proposals are adopted (or adapted) at state and local levels. Critics contend that the ICC process can be opaque and heavily influenced by industry stakeholders, while defenders say code changes receive expert review and public input. Either way, many advocates call for more transparent, evidence-driven cost-benefit analysis when rules change.

Longer-term reform ideas include broader use of performance-based codes, which set required safety outcomes without mandating specific technologies, and federal support for more consistent, transparent code processes. These approaches aim to preserve safety while reducing unnecessary barriers to building more homes.

Bottom Line

Raising the cost of building housing — intentionally or not — means less housing gets built. To restore supply and affordability, policymakers must look past zoning to the many technical rules that silently shape whether small multifamily homes are feasible. Targeted, evidence-based reforms can make missing-middle housing practical without compromising safety.

Help us improve.