ESA has approved the Draco mission to record, in situ, what happens when a spacecraft breaks up during atmospheric reentry. The 150–200 kg, 40 cm capsule will carry ~200 sensors and four cameras and is planned to reenter deliberately over an uninhabited ocean about 12 hours after orbit insertion. Data downlink is expected during a roughly 20-minute window after parachute deployment before splashdown. Results will validate reentry models, inform 'design for demise' spacecraft, and help assess safety and upper-atmosphere pollution impacts.

What Really Happens When a Satellite Burns Up? ESA's Draco Mission Will Find Out

The European Space Agency (ESA) has approved a new mission, Draco (Destructive Reentry Assessment Container Object), to directly measure what happens when a spacecraft breaks up during reentry into Earth's atmosphere. Draco is purpose-built to produce a controlled, highly instrumented destructive reentry so scientists can gather measurements that are impossible to obtain on the ground.

Mission Overview

Planned for launch in 2027, Draco is a compact capsule roughly the size of a washing machine — about 40 cm (1.3 ft) in diameter — and expected to weigh 150–200 kg (330–440 lb). The capsule will be inserted into orbit and deliberately made to reenter over an uninhabited ocean region roughly 12 hours after orbit insertion.

What Draco Will Measure

Draco will carry roughly 200 sensors and four high-speed cameras. Instruments will record temperatures, mechanical strain on components, and ambient pressure as the vehicle encounters progressively denser air and extreme heating. The cameras will capture the breakup sequence to provide visual context for the instrument data.

Data Handling and Downlink

During the high-heat phase measurements will be recorded onboard. In the final stage a parachute will deploy and the capsule will attempt to connect to a geostationary relay to downlink stored data. ESA planners expect about a 20-minute telemetry window to transmit the measurements before the capsule splashes down in the ocean and the mission ends.

Why This Matters

Draco supports ESA's broader Zero Debris objective and the agency's 'design for demise' efforts, which aim to reduce long-lived debris in orbit by encouraging spacecraft designs that fully disintegrate on reentry. In-situ measurements from an actual destructive reentry will validate and improve reentry and ablation models that are today constrained to wind-tunnel tests and computer simulations.

Holger Krag, Head of Space Safety at ESA: 'We need to gain more insight into what happens when satellites burn up in the atmosphere as well as validate our re-entry models. The unique data collected by Draco will help guide the development of new technologies to build more demisable satellites by 2030.'

Safety and Atmospheric Impact

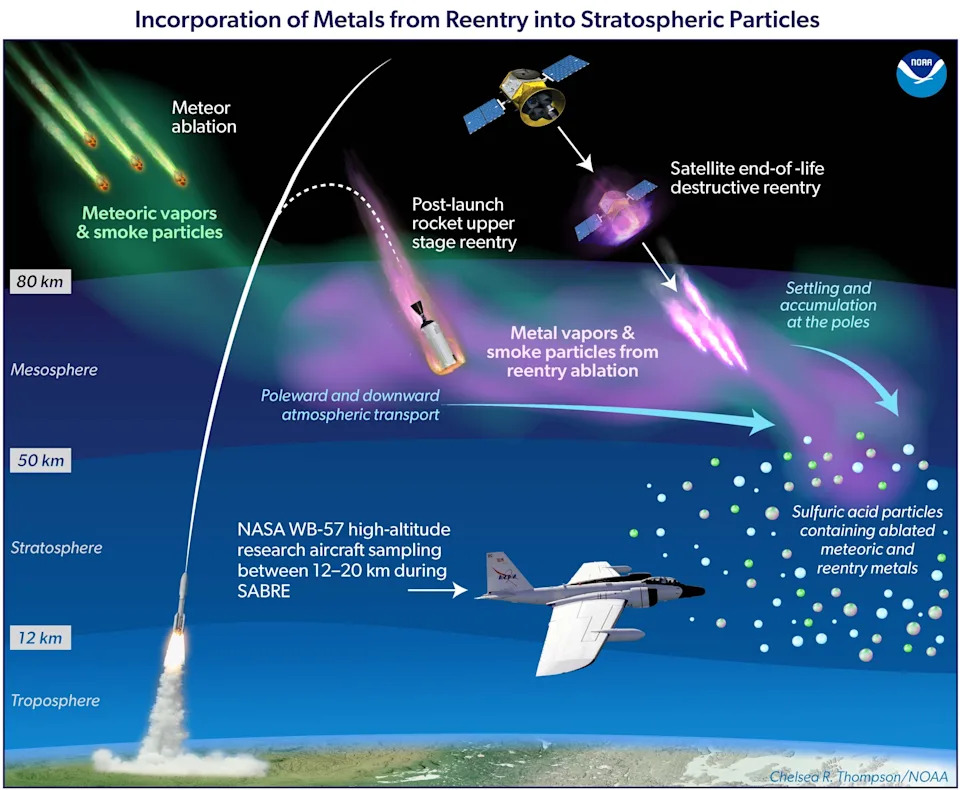

Experts stress two linked concerns: casualty and air-traffic risks on one hand, and atmospheric pollution on the other. Uncontrolled reentries can pose a small but real risk to people and aircraft and may trigger disruptive airspace closures. On the atmospheric side, ablation products — the particles and gases produced as materials burn and vaporize — are deposited directly into the upper atmosphere, where they can affect aerosol chemistry, ozone, and climate-related processes.

Aaron Boley, Professor (University of British Columbia): 'Direct experiments that observe satellite breakup in situ and characterize the emission products produced during reentry are very valuable for tackling the linked challenges of safety and atmospheric pollution.'

Community Reaction

Independent researchers welcome the mission. Leonard Schulz (Technische Universität Braunschweig) called in-situ measurements 'an important piece of the puzzle' and a potential pathfinder for future fragmentation studies. Luciano Anselmo (National Research Council, Italy) noted that although Draco will represent a single, well-characterized reentry scenario, a successful experiment could yield broadly applicable insights and reveal unexpected phenomena.

What Success Would Mean

If Draco performs as planned, its 'real-world' dataset will help engineers design satellites that reliably disintegrate on reentry, reduce the creation of hazardous debris in orbit, and better quantify how reentry emissions interact with the upper atmosphere. Those advances would aid space sustainability, reduce ground and air safety risks, and inform environmental impact assessments for future missions.

Key mission facts: planned launch 2027; mass ~150–200 kg; ~40 cm capsule; ~200 sensors + 4 cameras; deliberate reentry ~12 hours after orbit insertion; ~20-minute telemetry window after parachute deployment; targeted splashdown in an uninhabited ocean area.

Help us improve.