The Supreme Court decision in Egbert v. Boule, authored by Justice Clarence Thomas, has significantly narrowed the ability to bring Bivens-style constitutional claims against federal officers, limiting accountability for ICE and Border Patrol. Since July, DHS agents have reportedly shot at least 16 people, and Alex Pretti suffered prior abuse before his fatal shooting. Advocates urge Congress to restore a private right of action—often called the Bivens fix—so federal officers can be sued under rules similar to state officers under 42 U.S.C. § 1983. Linking that reform to DHS funding could be an effective political lever to force meaningful change.

Take the Fight With ICE Out of the Streets and Into the Courts: Restore Accountability After Egbert v. Boule

There is only one place to take the fight over federal immigration enforcement: the courts. The deaths of Renee Good and Alex Pretti, and a wider pattern of forceful federal interventions, show how urgently Americans need a clear legal pathway to hold federal officers accountable.

Egbert v. Boule dramatically narrowed the circumstances in which people can seek a federal constitutional remedy against federal officers. The Supreme Court's decision, written by Justice Clarence Thomas, has had the practical effect of limiting Bivens-style claims and making it far harder for victims of excessive force by federal immigration agents to vindicate constitutional rights in court.

As a consequence, many actions by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Border Patrol that would give rise to suits against state officers under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 no longer produce a comparable remedy when federal officers are involved. Instead, victims are often left with internal agency grievance processes that are closed to meaningful public participation and offer limited, if any, independent review.

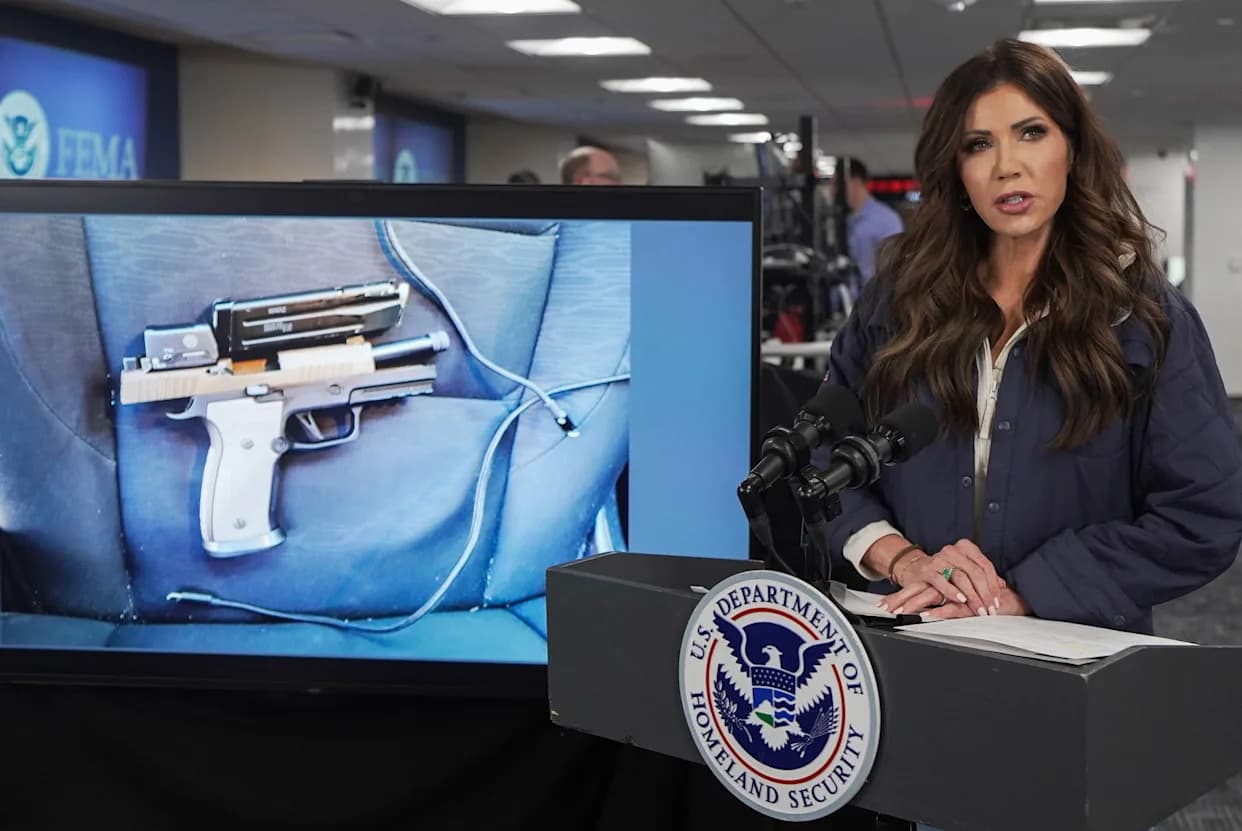

The human cost is real. Since July, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has reportedly shot at least 16 people. The cases of Good and Pretti stand out: Pretti suffered a broken rib following an encounter with ICE agents a week before he was fatally shot, and both deaths have raised questions about whether the current accountability framework is adequate.

Accountability does more than punish wrongdoing — it deters it. A robust private right of action encourages transparency: officers who know their conduct may be examined in an open court are more likely to follow constitutional limits. By contrast, anonymity and internal-only reviews can foster impunity. Masks, withheld identities, and agency-controlled investigations erode public trust and deny victims a meaningful forum for redress.

A legislative fix is straightforward in concept: restore a private cause of action for constitutional violations by federal officers. Advocates describe this approach as adding a short textual fix — colloquially referred to as the "Bivens Act" — to place federal officers under the same rules that have governed state officers under § 1983 since 1871. That change would not be about retribution; it would be about restoring parity, transparency, and judicial oversight.

Politically, passage will be difficult. Executive and political defenders of aggressive federal deployments oppose expanding litigation exposure for agents. But legislative leverage exists: Congress must regularly act to fund DHS, and that appropriations process offers a potential route for insisting on meaningful structural reform rather than only technical, operational changes like requiring body cameras or removing masks.

The Constitution does not enforce itself. If Congress restores or creates a clear statutory remedy to allow victims to bring claims in court, federal officers would be brought under judicial review more consistently — and the public would regain an essential tool for holding power to account.

About the author: Chris Truax is an appellate attorney and charter member of the Society for the Rule of Law.

Copyright 2026 Nexstar Media, Inc. All rights reserved.

Help us improve.