New study links Hawaii’s “Sharktober” spike in unprovoked bites to tiger shark pupping season. Researchers analyzed 30 years (1995–2024) of records and found 165 incidents, with tiger sharks accounting for 47% overall and at least 63% of October bites. Large pregnant females migrate nearshore to give birth, and the energetic demands of reproduction — plus seasonal prey patterns — likely increase encounters, though the overall bite risk remains very low.

‘Sharktober’ In Hawaii Tied To Tiger Shark Pupping Season, Study Finds

New research finds a clear October spike in unprovoked shark bites off Hawaii — a pattern commonly called “Sharktober” — and links it to the seasonal movement and reproductive biology of tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier).

Carl Meyer, a marine biologist at the University of Hawai'i at Manoa’s Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology, reviewed 30 years of shark-bite records (1995–2024). He identified 165 unprovoked bites in Hawaiian waters during that period and found tiger sharks were responsible for 47% of those incidents, while 33% involved unidentified species and 16% were attributed to requiem sharks (Carcharhinus spp.).

About 20% of all recorded bites occurred in October — a rate two to four times higher than in other months — even though there is no evidence that more people are entering the water for recreation at that time. During October specifically, tiger sharks accounted for at least 63% of documented bites; another 28% involved unidentified sharks that could include tiger sharks, Meyer reported in a study published Jan. 6 in Frontiers in Marine Science.

“The October spike appears to be driven by tiger shark biology rather than changes in human ocean use,” Meyer told Live Science via email.

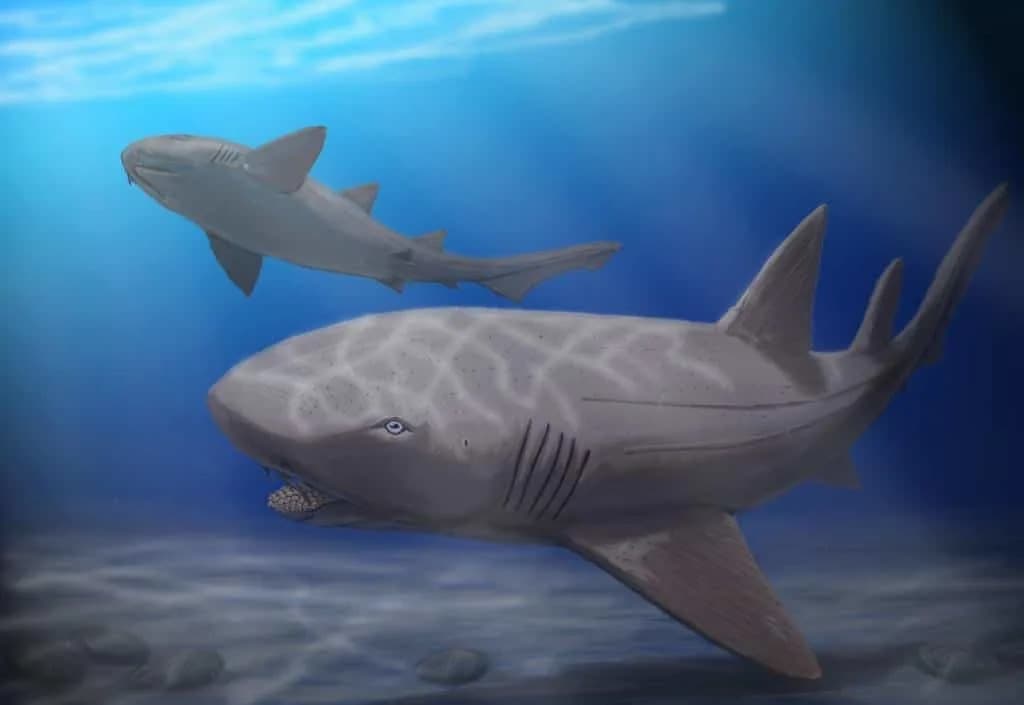

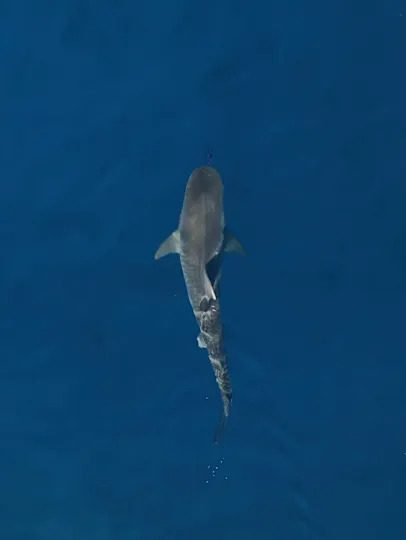

Ecotourism operators and Meyer’s data both indicate tiger shark numbers near Hawaii peak in October. This period coincides with a seasonal migration in which large, mature female tiger sharks move from islands in the northwest Pacific toward nearshore waters around the main Hawaiian Islands to give birth. The increased presence of large adult females in coastal areas likely increases the chance of human–shark encounters.

Why Pupping Season May Increase Bite Risk

- Migration to Nearshore Waters: Many large females move into coastal areas to pup, raising local shark abundance.

- Energetic Demands: Tiger sharks are ovoviviparous; females typically give birth to about 30 pups after a 15–16 month gestation. Pregnancy and post-birth recovery increase their need to forage actively.

- Prey Availability: Seasonal increases in preferred prey, such as large reef fish, may further concentrate sharks near shore.

Meyer noted that maternal protection of pups is unlikely to explain the spike: tiger shark pups are independent at birth and often remain in shallow areas to reduce predation by larger sharks, including adults of their own species.

Daryl McPhee, an environmental scientist at Bond University (not involved in the study), said the data are consistent with a broader principle: any seasonal change that increases overlap between large coastal sharks and people can raise the likelihood of a bite. He emphasized that, despite these patterns, the overall risk of being bitten remains very low.

Similar seasonal patterns appear elsewhere. For example, bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas) are suspected in a recent cluster of bites near Sydney, Australia; those events coincided with local breeding season and environmental conditions — heavy rain, runoff and murky water — that concentrated sharks and their prey near shore.

Long-term datasets also show an upward trend in recorded unprovoked bites in many regions. The Florida Museum’s records indicate global increases across decades (157 attacks in the 1970s; ~500 in the 1990s; 803 between 2010 and 2019). Regionally, New South Wales recorded four bites between 1980 and 1999 but 63 between 2000 and 2019.

Takeaway

Meyer’s main message is caution, not alarm: the October spike in Hawaii appears linked to tiger shark reproductive movements and biology, and people should exercise extra care during this month — especially when undertaking solitary ocean activities like surfing or swimming nearshore. The absolute risk of a shark bite remains very low.

Help us improve.