Police in Srinagar have circulated a four-page "profiling of mosques" form that requests institutional details and extensive personal data on imams and mosque staff. Residents and religious bodies say the exercise is intrusive and risks undermining privacy and religious freedom, while officials defend it as necessary for accountability and security. Critics urge transparency, judicial oversight and community involvement, warning the move may deepen distrust in a region already affected by restrictions since the 2019 revocation of Article 370.

India’s Mosque 'Profiling' in Kashmir Sparks Privacy and Religious-Freedom Fears

Mohammad Nawaz Khan says he regrets the day his father, Sanaullah Khan, agreed to chair the managing committee of their neighbourhood mosque in Srinagar, the main city of Indian-administered Kashmir. Nawaz’s concerns mounted after police began distributing a four-page document literally titled "profiling of mosques" to field staff across the city — a move residents and religious leaders say amounts to intrusive surveillance.

One page of the form collects institutional details about a mosque: its declared "ideological sect," year of establishment, sources of funding, monthly expenditure, capacity for worshippers, and land ownership. The other three pages request extensive personal information about imams, muezzins, khatibs and other mosque staff — including mobile numbers, email addresses, passport numbers, credit‑card and bank-account details.

What the Form Asks

Alongside routine identifying information, the form includes more sensitive fields: whether staff have relatives abroad, what "outfit" they are associated with, the model of their mobile phone and social-media handles. An almost identical questionnaire has been circulated among madrasa administrators in the region.

"This is not a place where you can live in peace. Every now and then, we are asked to fill out one form or another," Nawaz, 41, told Al Jazeera from his grocery shop in Jawahar Nagar. "Keeping such detailed records is not safe for families like mine. In a conflict area like Kashmir, this can have serious consequences."

"If this were just paperwork, the police would not have been asking for so many personal details again and again," said Hafiz Nasir Mir, an imam in Lal Bazar who has led daily prayers for 15 years. "They want information about relatives who live outside Kashmir or even outside India. These are private family matters, not things meant for police records."

Official Responses and Local Reaction

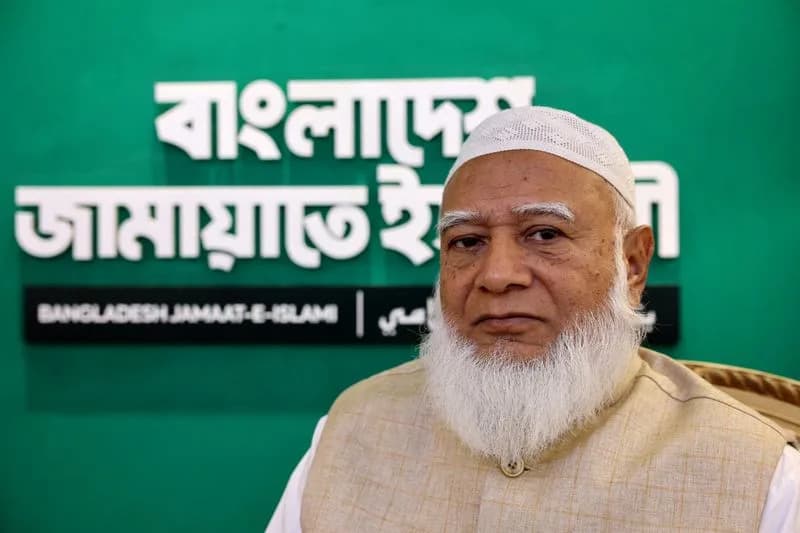

The Mutahida Majlis-e-Ulema (MMU), the largest umbrella body of Islamic religious groups in Kashmir, demanded an immediate halt to the exercise, calling it an attempt to control religious institutions. Local politicians — including Mehbooba Mufti, a former chief minister — criticised the profiling as discriminatory and said it creates fear among Muslims.

Imran Nabi Dar, spokesman for the governing National Conference, said the party would raise the issue with the New Delhi‑appointed lieutenant governor and called the additional survey unnecessary. The region regained an elected government in 2024, but many executive powers remain with the union territory administration.

Defending the profiling, Altaf Thakur, a BJP spokesman in Kashmir, argued that such information is needed for accountability and to prevent mosques from being exploited as platforms for political mobilisation. He pointed to past instances where religious platforms were used to encourage public demonstrations he described as "pro‑Pakistan" in character.

Context And Concerns

The Himalayan region of Kashmir is disputed between India and Pakistan, and a small portion is administered by China. In 2019, the Indian government revoked Article 370 — which had granted special autonomy to Indian‑administered Kashmir — and reorganised the area into two federally administered union territories: Jammu and Kashmir, and Ladakh. Since then, critics say the central government has increased its control over many aspects of daily life in the valley, including religious activities.

Srinagar’s Jamia Masjid — the valley’s principal mosque — was closed for almost two years after the 2019 decision and has faced periodic closures and limits on congregational numbers during major religious holidays. Residents say repeated data collection drives, now including the mosque profiling form, feel less like routine record‑keeping and more like an effort to monitor and control Muslim religious life.

Analysts and community leaders have called for a balanced approach that ensures security while protecting privacy and religious freedom: clear rules, transparency, judicial oversight and meaningful involvement of local communities in any data‑collection exercise. Many observers also voiced concern that the profiling appears to single out Muslim institutions without similar scrutiny of other faiths, which could deepen perceptions of discrimination.

Why It Matters: In a sensitive, contested region with a long history of political and social tensions, the gathering and storage of detailed personal and institutional data by law‑enforcement agencies raises acute questions about civil liberties, the potential for misuse, and the trust between citizens and authorities.

Help us improve.