Ancient Mesopotamia recognized gender-diverse people in formal religious and political roles as early as 4,500 years ago. The assinnu served Ištar and were described in texts as gender-fluid, with ritual, healing and political authority. The ša rēši were beardless royal courtiers who supervised women’s quarters, commanded troops and received governorships. Evidence shows these roles were powerful because they crossed the gender binary, not because they fit reductive labels like "eunuch."

How Gender-Fluid Roles Gave People Power in Ancient Mesopotamia (4,500 Years Ago)

Today, transgender and gender-diverse lives are often politicized and attacked. Yet some of the world’s earliest civilizations recognized and even rewarded people who crossed gender boundaries. In ancient Mesopotamia — roughly modern Iraq and parts of Syria, Turkey and Iran — gender-ambiguous individuals held formal religious and political offices as early as 4,500 years ago.

Mesopotamia: A Brief Context

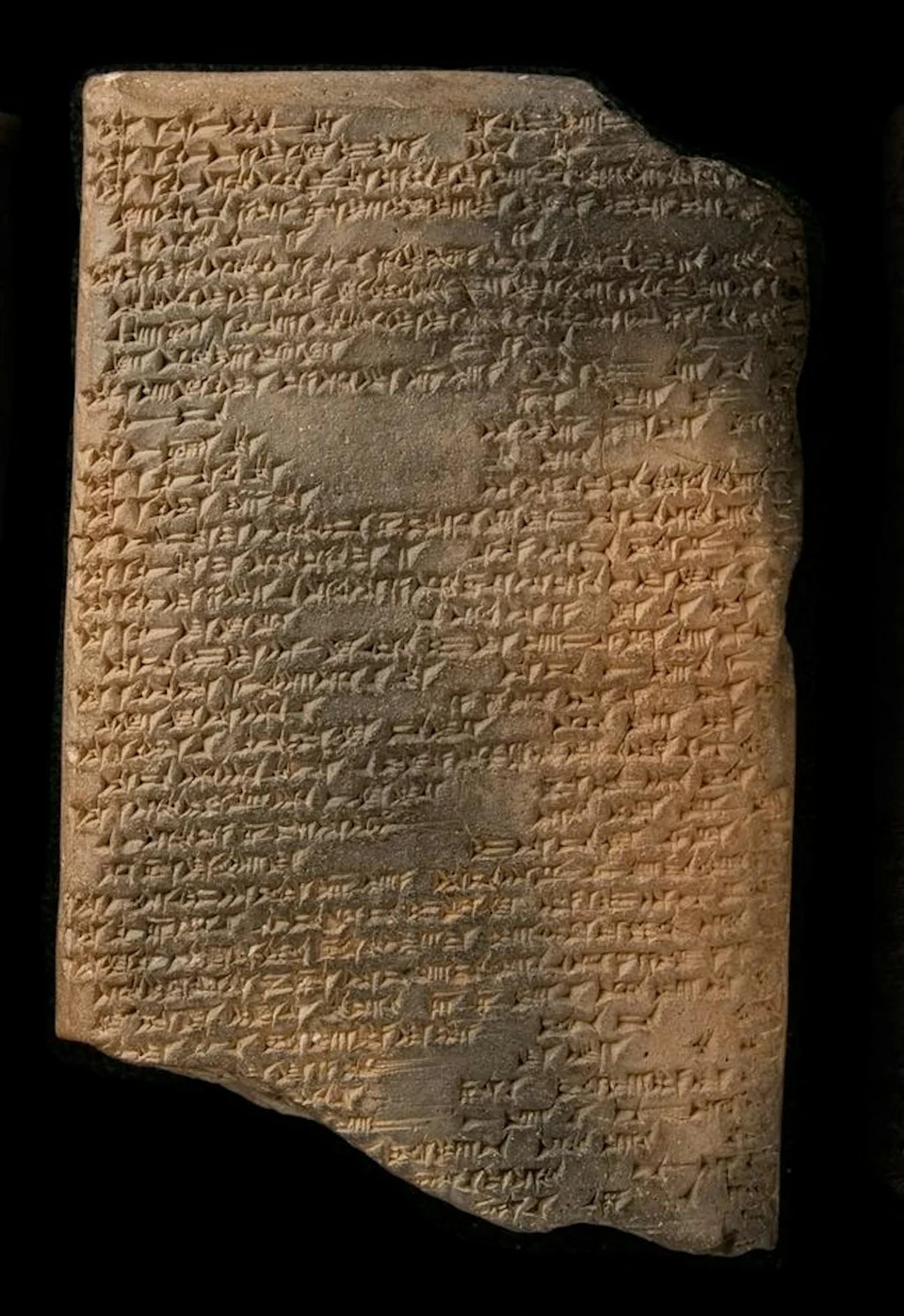

Mesopotamia, the "land between two rivers" (the Euphrates and Tigris), was home to successive cultures including the Sumerians, Akkadians, Assyrians and Babylonians. The Sumerians invented cuneiform writing — wedge-shaped impressions on clay — a system later used to record Akkadian dialects and the administrative, religious and literary texts that inform our knowledge of social roles in the region.

Assinnu: Devotees of Ištar

The assinnu served the major Mesopotamian goddess Ištar (Sumerian Inanna), a potent deity of love, sexuality, fertility and war who also legitimized kingship. The Akkadian term assinnu relates to words meaning "woman-like" and "man-woman," and can carry connotations of "hero" or "priestess." Texts present their gender fluidity as bestowed by Ištar herself, allowing them to operate between divine and human spheres.

turn a man into a woman and a woman into a man

to change one into the other

to dress women in clothes for men

to dress men in clothes for women

to put spindles into the hands of men

and to give weapons to women.

Earlier scholars sometimes labeled assinnu as cultic sex workers or eunuchs, but the evidence does not clearly support those narrow classifications. Texts attest to both male- and female-designated assinnu, and many sources show they resisted a rigid gender binary. Their ritual position conferred perceived magical and healing powers — for example, an incantation requests that an assinnu remove illness — and they could also exert political influence. A Neo-Babylonian almanac even links royal ritual contact with an assinnu to military success and political obedience.

Ša Rēši: Beardless Courtiers and Trusted Agents of the King

The title ša rēši (literally "one of the head") designated close royal attendants who served in varied senior capacities. Although older scholarship often calls them "eunuchs," Mesopotamia had its own distinct office and vocabulary. Textual and visual evidence suggests ša rēši were portrayed as beardless and sometimes described as infertile, distinguishing them from bearded courtiers (ša ziqnī) whose beard signaled masculine adulthood.

Ša rēši commonly supervised the palace women's quarters — a restricted, gendered space accessible only to the king. Their intimate access and trust allowed them to serve as guards, charioteers and military leaders; successful ša rēši could receive land, governorships and even erect royal inscriptions in their own name. By occupying roles that crossed standard gendered boundaries, they could bridge social divisions between ruler and subject.

Evidence Versus Misconception

Both assinnu and ša rēši appear in administrative texts, hymns, omens and reliefs. These sources show that Mesopotamians recognized nonbinary or gender-fluid identities and attached public authority to them. Interpreting these roles simply as "eunuchs" or "cultic sex workers" reflects modern biases and the limits of early scholarship rather than the full nuance of the ancient record.

Legacy and Relevance

Understanding assinnu and ša rēši helps correct misconceptions about ancient gender systems and highlights a historical continuity: communities across time have recognized people who do not conform to a strict gender binary, and sometimes entrusted them with significant religious and political responsibilities. Recognizing this complexity enriches both historical scholarship and modern conversations about gender diversity.

Adapted from research first published in The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Help us improve.