The Halaf culture's painted pottery from northern Mesopotamia (c. 6000 BCE) contains the oldest known botanical art and hints at early abstract thinking. Researchers Yosef Garfinkel and Sarah Krulwich analyzed motifs from 29 sites and found plant images that likely reflect aesthetic appreciation rather than depictions of crops. Many bowls show petal counts following a geometric progression (4, 8, 16, 32, and occasional 64), suggesting visualized mathematical reasoning centuries before written numbers. The findings are published in the Journal of World Prehistory.

6,000‑BCE Halaf Pottery Shows Botanical Art — Evidence of Early Mathematical Thought

New research finds that the earliest known botanical decorations — painted on pottery made by the Halaf culture in northern Mesopotamia around 6000 BCE — conceal cultural and cognitive shifts beneath deceptively simple designs. Archaeologists Yosef Garfinkel and Sarah Krulwich of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem argue that these decorated vessels mark an early turn toward seeing plants as subjects of artistic value and that the counting visible in flower petals points to an unexpectedly sophisticated numerical sensibility.

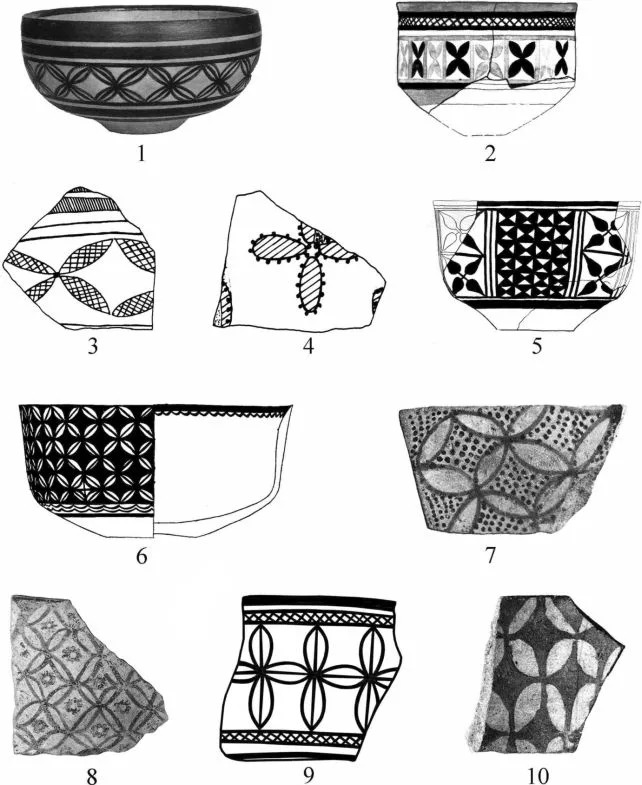

The team systematically cataloged, compared and analyzed plant-like motifs on Halaf pottery from 29 archaeological sites. They note that recognizing such motifs often requires interpretation and that many sherds they classify as plant-decorated were not identified as such in earlier publications.

What the researchers found: The figures — including stylized flowers, seedlings, shrubs, branches and tall tree forms — appear not to represent agricultural crops, since the species depicted are not food plants. Instead, the images seem rooted in an aesthetic appreciation of plant form and symmetry, and in a visual awareness of numerical patterns.

Garfinkel suggests the ability to divide space evenly, visible in the floral designs, could have practical origins in everyday communal tasks such as dividing harvests or allocating fields. This practical impulse, he argues, is expressed visually through motifs that are evenly distributed across vessel surfaces and repeated in strict, ordered sequences.

Most striking is the numerical detail in many floral motifs: petal counts that follow a geometric progression — 4, 8, 16 and 32 — with some vessels showing groupings consistent with 64. The authors interpret this deliberate progression as strong evidence that people used visual art to express concepts of division, sequence and balance long before numeric signs appeared in writing.

"These vessels represent the first moment in history when people chose to portray the botanical world as a subject worthy of artistic attention," say Yosef Garfinkel and Sarah Krulwich of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

"It reflects a cognitive shift tied to village life and a growing awareness of symmetry and aesthetics."

The study, published in the Journal of World Prehistory, emphasizes interpretive caution: motif identification involves judgment, and alternative explanations (ritual symbolism, cosmological meanings, or unpreserved plant varieties) cannot be ruled out. Nonetheless, the consistent numeric patterns across many vessels provide compelling evidence that early villagers visualized and applied mathematical ideas centuries — in some cases millennia — before the appearance of written numerals such as the proto-cuneiform signs of southern Mesopotamia (c. 3300–3000 BCE).

Implications: If borne out by further research, these findings expand our understanding of how early communities combined artistic expression, daily practical needs and abstract thinking. The Halaf pottery suggests that mathematical concepts such as division, sequence and geometric growth may have been part of visual and social practices long before they were encoded in writing.

Help us improve.