The skeleton of a 16–18-year-old from Kozareva Mogila in eastern Bulgaria shows puncture and compressive cranial injuries that researchers attribute to a lion attack about 6,200 years ago. Comparative molding and tooth-impression analysis point to Panthera leo as the likely attacker. Signs of healing indicate he survived roughly two to three months and probably received community care, but he appears to have later died from complications. A deep, goods-free burial suggests he may have been feared or socially marginalized after the mauling.

Teen Survived Lion Mauling 6,200 Years Ago, Skull Shows — But Wounds Likely Proved Fatal

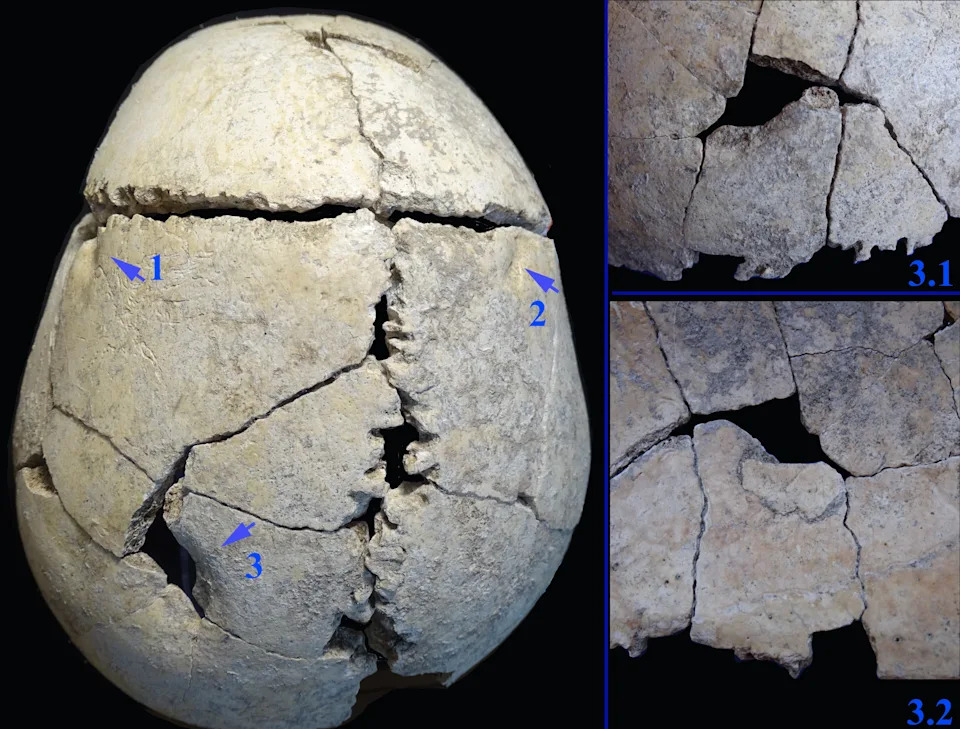

About 6,200 years ago a teenager in what is now eastern Bulgaria endured a brutal attack by a very large carnivore and lived long enough for some wounds to begin healing, a new study reports. Analysis of his skeleton indicates severe puncture and compressive damage to the skull consistent with a big-cat bite rather than human-made weapons or postmortem damage.

How Researchers Identified the Attacker

The remains, recovered near the Copper Age settlement of Kozareva Mogila ("Goat Mound"), belong to an individual estimated at 16–18 years old. To identify the likely attacker, researchers led by archaeozoologist Nadezhda Karastoyanova compared the pattern of damage on the skull with moldings and bite-impression matches made from lion and bear skulls in the National Museum of Natural History of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences collection. Considering tooth spacing, defect size and the known distribution of large carnivores during the Copper Age, the team concluded that a lion (Panthera leo) was the most probable assailant.

"The skull shows a specific pattern of puncture and compressive injuries that are inconsistent with human-made weapons or postmortem damage," Karastoyanova said. "The size, shape, depth, and spacing of the defects are compatible with trauma produced by the bite of a very large carnivore."

Injuries, Survival, and Care

The pattern of wounds suggests the animal knocked the youth down and bit his head repeatedly. Some cranial defects penetrate deeply enough that the researchers believe the meninges — the membranes lining the brain — were likely damaged, leaving brain integrity in a "questionable" state. The teenager's legs and left arm also show deep lesions that probably damaged muscle and tendon attachments, producing lasting disability.

Importantly, the cranial injuries display signs of healing consistent with roughly two to three months of recovery, which indicates he survived the initial attack and may have received care from others. However, the healing is limited, and the team infers he ultimately died from complications related to his wounds.

Burial, Social Consequences, and Local Medical Knowledge

The boy was buried in a deep, crouched grave with his hands held in front of his face and without grave goods. He measured about 175 centimeters (5 feet 9 inches) in height. The unusually deep burial and absence of accompanying items suggest the community may have feared or socially marginalized him after the mauling.

Finds from Kozareva Mogila indicate the community had some medical expertise — including evidence of cranial operations on both living and deceased individuals — which may explain how the teenager survived long enough to show healing. Nevertheless, his disfiguring head, arm and leg injuries would likely have left prominent scars and substantial disability, preventing him from performing strenuous tasks such as farming and possibly causing lasting neurological impairment.

Why This Case Matters

Direct prehistoric evidence of large-carnivore attacks on humans is rare. This skeleton offers a striking, multi-faceted glimpse into Copper Age life on the Black Sea’s inland margin: the dangers people faced from large predators, the community responses that enabled short-term survival, and the social consequences for an injured and disfigured individual.