A study published Nov. 3 in Ñawpa Pacha reports the first documented orofacial cleft in an Andean trophy head. Photographs of a mummified Peruvian specimen examined by Beth Scaffidi (UC Merced) indicate a cleft lip, yet the individual survived into early adulthood. The finding implies attentive caregiving in infancy and supports evidence that congenital differences could carry social or spiritual significance in some ancient Andean communities.

Ancient Peruvian Trophy Head Shows Cleft Lip — Individual Survived Into Adulthood, Study Finds

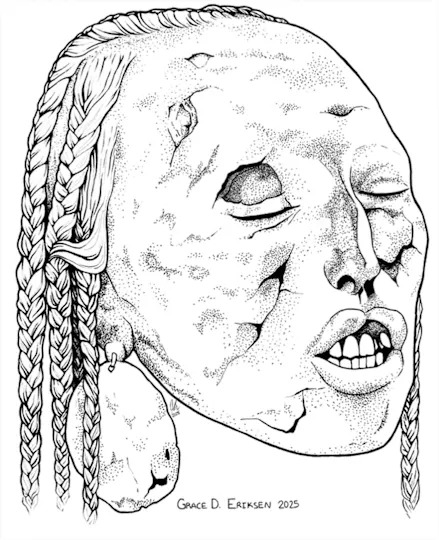

Centuries-old photographs of a mummified Peruvian trophy head reveal that the person had a cleft lip yet lived into early adulthood, according to a new study. The diagnosis — made from museum images by Beth Scaffidi, an assistant professor of anthropology and heritage studies at the University of California, Merced — is the first documented case of an orofacial cleft in an Andean trophy head.

Scaffidi published her findings on Nov. 3 in the journal Ñawpa Pacha after examining a specimen catalogued at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Saint-Étienne, France, which is reportedly from the Ica Department near Nazca on coastal Peru. Based on preserved facial anatomy in the photographs, she judged the individual to be probably male and a young adult at death, and identified an unrepaired cleft lip.

What Is an Orofacial Cleft?

Orofacial clefts — the umbrella term for cleft lip and cleft palate — occur when the lip and/or roof of the mouth fail to fuse during fetal development. Modern data place the global incidence at roughly 1 in 700 live births. Diagnosing these conditions in archaeological remains is uncommon: about 50 archaeological cases have been reported worldwide to date.

Context: Andean Trophy Heads and Social Meaning

For millennia, people in parts of the Andes collected and processed severed heads for preservation and display. Most known trophy heads from the region date to roughly 300 B.C.–A.D. 800. These objects were often naturally mummified in the arid coastal deserts and may have been passed down as heirlooms. Scholars debate whether they represent revered ancestors or spoils of violent conquest; many heads show injuries inflicted near the time of death.

Scaffidi argues that the presence of a congenital facial difference in a trophy head offers a rare window into how ancient Andean communities perceived disability and difference. Drawing on iconographic evidence — particularly ceramic art from the Moche culture (A.D. 200–850) — she notes that orofacial clefts are sometimes depicted on elite, male figures shown with jewelry, wrapped heads, or shamanic and medical roles. This pattern suggests that in some Andean contexts congenital facial differences could carry social or spiritual significance rather than stigma.

Implications for Care and Status

Orofacial clefts can cause early-life challenges, most notably difficulty breastfeeding, as well as respiratory, hearing and speech problems. In the modern era, such defects are often repaired surgically in infancy. In the ancient Andes, survival to adulthood would likely have required attentive caregiving. Scaffidi suggests that the studied individual not only survived but may have been considered special or sacred, possibly enjoying elevated status in life and in death.

“This finding is important because it shows that people survived, and even thrived, with this condition in the ancient Andes,” Scaffidi wrote. “It helps show that what we define as a disability and how we respond to it is culturally, rather than biologically, determined.”

While some trophy heads may have been taken from enemies, previous research indicates many were selected for perceived supernatural power; takers may have believed they could harness such power for community benefit. The cleft lip on this specimen is therefore consistent with the idea that congenital differences were sometimes celebrated rather than shunned.

Further research — including direct examination of remains, contextual archaeological study, and comparison with regional art and iconography — could deepen understanding of how congenital conditions were treated and conceptualized across different Andean societies.

Help us improve.