Project Suncatcher proposes running data centers from fleets of solar-powered satellites to meet AI’s growing energy needs. While space-based TPUs could deliver large amounts of compute, the plan risks increasing orbital debris, worsening light pollution, and triggering geopolitical competition for space. The piece calls for stronger international rules — akin to an Antarctic Treaty or targeted licensing and debris mitigation — to protect orbital commons and reduce long-term hazards.

Google’s Project Suncatcher: Powering AI from Solar Satellites — But at What Cost?

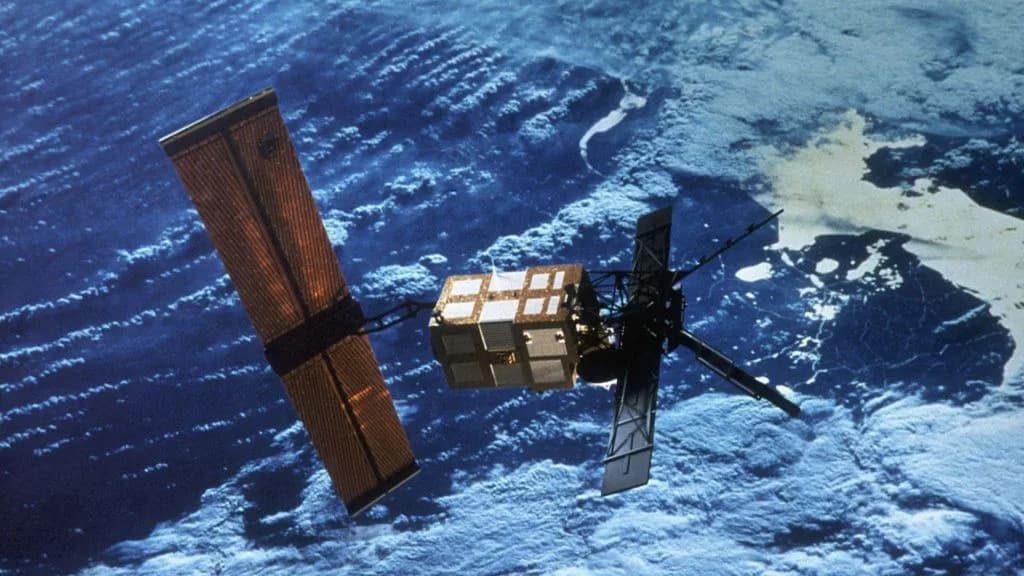

Earlier this month, Google researchers published a paper outlining “Project Suncatcher,” a speculative concept to build data centers in orbit to meet the soaring energy demands of advanced artificial intelligence. The proposal envisions a constellation of solar-powered satellites carrying tensor processing units (TPUs) — the specialized chips that run many of Google’s AI models — and suggests this fleet could be “significantly larger … than any previous or current satellite constellations.”

The paper frames the project as a response to the rapidly rising electricity needs of large-scale AI systems. In space, satellites could harvest uninterrupted sunlight and potentially deliver huge amounts of energy for compute-heavy workloads. But the plan raises immediate technical, environmental, and geopolitical questions.

What Project Suncatcher Would Mean

Rather than a single monolithic structure, Project Suncatcher imagines many satellites working together as distributed data centers. Because on-orbit repair would be difficult or impractical, the researchers propose redundancy — extra processors and spare satellites stacked into the constellation so failures are tolerated without human intervention.

Google is far from the only group exploring this idea. The paper and public reporting note interest from private companies, former executives, and state-backed programs. That competition could accelerate launches and deployment, raising the possibility of large-scale orbital build-outs by multiple actors.

Key Concerns

Orbital debris and long-term congestion: Millions of additional satellites or spare units increase collision risk and create lasting debris that can endanger other spacecraft.

Astronomy and light pollution: Large constellations already interfere with telescopes and sky surveys; many more satellites would exacerbate these problems.

Geopolitical competition: If low Earth orbit becomes a contested resource, nations and corporations may race to dominate access and control, concentrating power.

The Suncatcher team’s redundancy approach — leaving many spare units in orbit to replace failed ones — could multiply hardware mass in space. Multiply Google-scale numbers of TPUs by several competing actors, and the result could be a dense ring of functioning and defunct hardware around Earth. That scenario is reminiscent of fictional depictions of cluttered orbits, but the underlying risk is real: collisions create more debris, and cleanup in space today is technically and politically complex.

On the Claim That AI Is “Foundational”

The Suncatcher paper describes AI as a “foundational general-purpose technology — akin to electricity or the steam engine.” That comparison is provocative but debatable. Current AI systems deliver powerful tools in many domains, yet they remain imperfect: they can hallucinate, produce erroneous outputs, and require considerable energy and data to scale. Even technology leaders have cautioned against overtrusting present-day models.

It’s reasonable to plan for future infrastructure needs, but it’s also appropriate to scrutinize whether moving vast computing capacity into orbit is the right or only solution — especially when it involves new environmental and ethical trade-offs.

Policy Options and Practical Remedies

Project Suncatcher highlights the need for international governance and technical safeguards. Possible approaches include:

- International agreements limiting commercial launches into specific orbital bands for non-scientific uses or requiring stricter licensing and environmental review.

- Mandatory debris mitigation: deorbiting plans, lifetime caps, and enforceable end-of-life requirements for satellites and spare hardware.

- Greater transparency: open registries of orbital assets, data-sharing about failure rates, and coordinated traffic-management systems.

- Investment in on-orbit servicing and recycling technologies that reduce the need for disposable redundancy.

An “Antarctic Treaty”–style framework for space has merit as a starting idea: it would require broad international buy-in and would have to be practical enough to enforce. Even without a sweeping treaty, targeted rules and global coordination could reduce the risk that orbital expansion becomes an unregulated arms race.

Conclusion

Project Suncatcher sketches an audacious solution to a real problem: the energy appetite of modern AI. But the proposal also underscores how infrastructure choices can create new environmental and political hazards. If companies and nations move toward orbit-based computing, policymakers, scientists, and the public should demand clear safeguards: debris mitigation, transparent licensing, and cooperative governance. Without those protections, the drive to power AI from space risks trading one set of planetary problems for a new and more permanent one above our heads.

Help us improve.