Lengthy Arctic blasts in late January and early February produced many daily low-temperature records and extended freezing streaks across the Eastern U.S., even as long-term data show winters are warming on average. Scientists say the apparent contradiction reflects complex interactions among a meandering jet stream, the stratospheric polar vortex, rapid Arctic warming, sea-ice loss and warmer oceans—processes still under active study. Climate models and multiple analyses indicate that, despite episodic severe cold events, winters are projected to become milder overall as greenhouse gas concentrations rise.

Icy Outbreaks Renew Questions: How Do Severe Cold Snaps Fit With A Warming World?

Lengthy Arctic blasts and deep freezes across much of the Eastern United States in late January and early February have reignited public confusion about how intense winter weather can occur while the planet warms.

Between Jan. 23 and Jan. 26 a powerful storm and polar air mass affected more than 30 states and was blamed for more than 120 deaths. Many daily temperature records fell in the period from Jan. 23 to Feb. 2, including 38 record low minimums and 45 record low maximums reported by the National Weather Service. Only 15 all-time daily record lows (maximums or minimums) were set, but multiple locations recorded long, unusual freezing streaks: nine consecutive days below freezing at Ronald Reagan National Airport (the second-longest on record), nine days at or below freezing in Central Park (the eighth-longest), and an eight-day tie in Jacksonville, Florida. Lake Erie also recorded its greatest ice coverage in 23 years at the start of February.

Why This Confuses People

Cold, snowy episodes can appear to contradict the longer-term trend of global warming, and social media and political comments have amplified that confusion. Part of the reason is that weather (short-term events) and climate (long-term trends) are different things. Another reason is scientific nuance: researchers are still untangling how multiple changing systems interact to produce cold-air outbreaks in midlatitude regions.

What Scientists Are Studying

Researchers are focused on several interacting elements:

- The Polar Jet Stream: A high-altitude river of air formed by temperature contrasts between the Arctic and lower latitudes. Its meanders can allow Arctic air to plunge southward.

- The Stratospheric Polar Vortex: A separate, higher-altitude circulation that sometimes experiences sudden warming events. When disrupted, it can influence weather patterns and help send Arctic air south.

- Rapid Arctic Warming and Sea Ice Loss: The Arctic is warming faster than most regions, altering temperature gradients and sea-ice extent; how these changes affect atmospheric circulation remains an active area of research.

- Warming Oceans: Warmer seas add moisture to the atmosphere, which can amplify snowfall where cold air and moisture converge.

- Large-Scale Oscillations: Natural patterns such as the Arctic Oscillation and El Niño–Southern Oscillation interact with the jet stream and vortex in complex, sometimes unclear ways.

Scientists quoted in recent studies and webinars emphasize that these systems are layered and interconnected. Some researchers, such as Judah Cohen, argue that interactions between the polar vortex and the jet stream can favor colder midlatitude conditions at times. Others, including Zeke Hausfather and a 2024 Canada–U.K. study, find that the frequency and intensity of midlatitude cold extremes have declined since 1990 and are consistent with climate-model predictions.

What The Evidence Shows

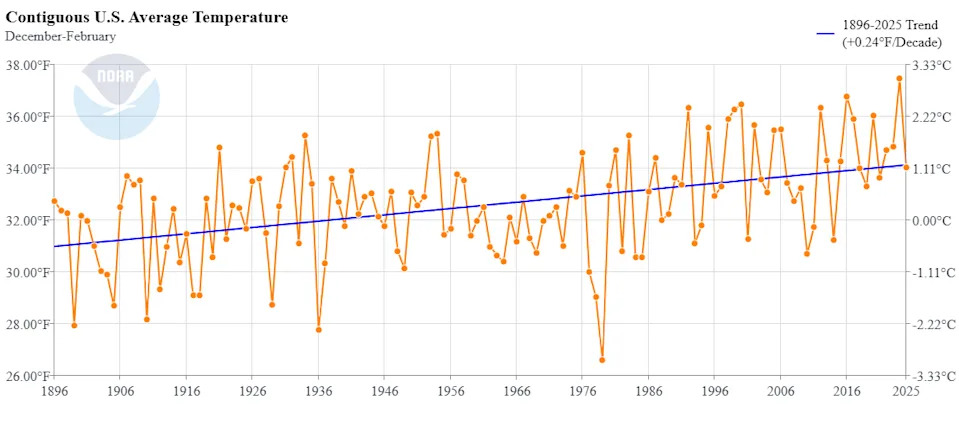

An international 2025 study that included U.S. scientists concluded that, despite ongoing cold outbreaks, abundant ice, snow and frigid Arctic winters will persist for decades—and that those cold conditions can still be displaced southward by Arctic heat events. At the same time, long-term climate records and models show winters are warming on average and that extreme cold events are not frequent enough to reverse the overall warming trend.

Experts also point out a social vulnerability: as winters warm on average, populations and infrastructure become less accustomed and less resilient to extreme cold, so occasional severe storms can have disproportionate impacts.

Bottom Line

Short-term cold outbreaks do not contradict the long-term trend of human-driven warming. Instead, they reflect the complexity of an atmosphere and oceans in transition: models overwhelmingly project milder winters over time even as episodic Arctic-driven cold spells continue to occur. Scientists are working to improve understanding of how rapid Arctic change, ocean warming, jet stream dynamics and natural variability combine to produce the winter extremes we experience.

Reporting note: This article synthesizes reporting and recent studies, including NOAA data and analyses from climate researchers and climate centers. For more context, see National Weather Service and NOAA releases on cold-weather records and peer-reviewed studies on Arctic–midlatitude linkages.

Help us improve.