NASA postponed February launch attempts for Artemis II after a wet dress rehearsal revealed multiple problems, chiefly liquid hydrogen leaks during tanking. Hydrogen’s tiny molecular size and extreme cryogenic storage temperature (about -423°F / -253°C) make seals prone to failure, a problem first seen during Artemis I. SLS uses heritage RS-25 shuttle engines that require liquid hydrogen due to a congressional design mandate, limiting fuel alternatives. Teams will inspect and repair seals on the pad, apply lessons learned, and must complete another wet dress rehearsal before Artemis II can fly.

Artemis II Delayed: Why Liquid Hydrogen Makes Rocket Fueling So Difficult

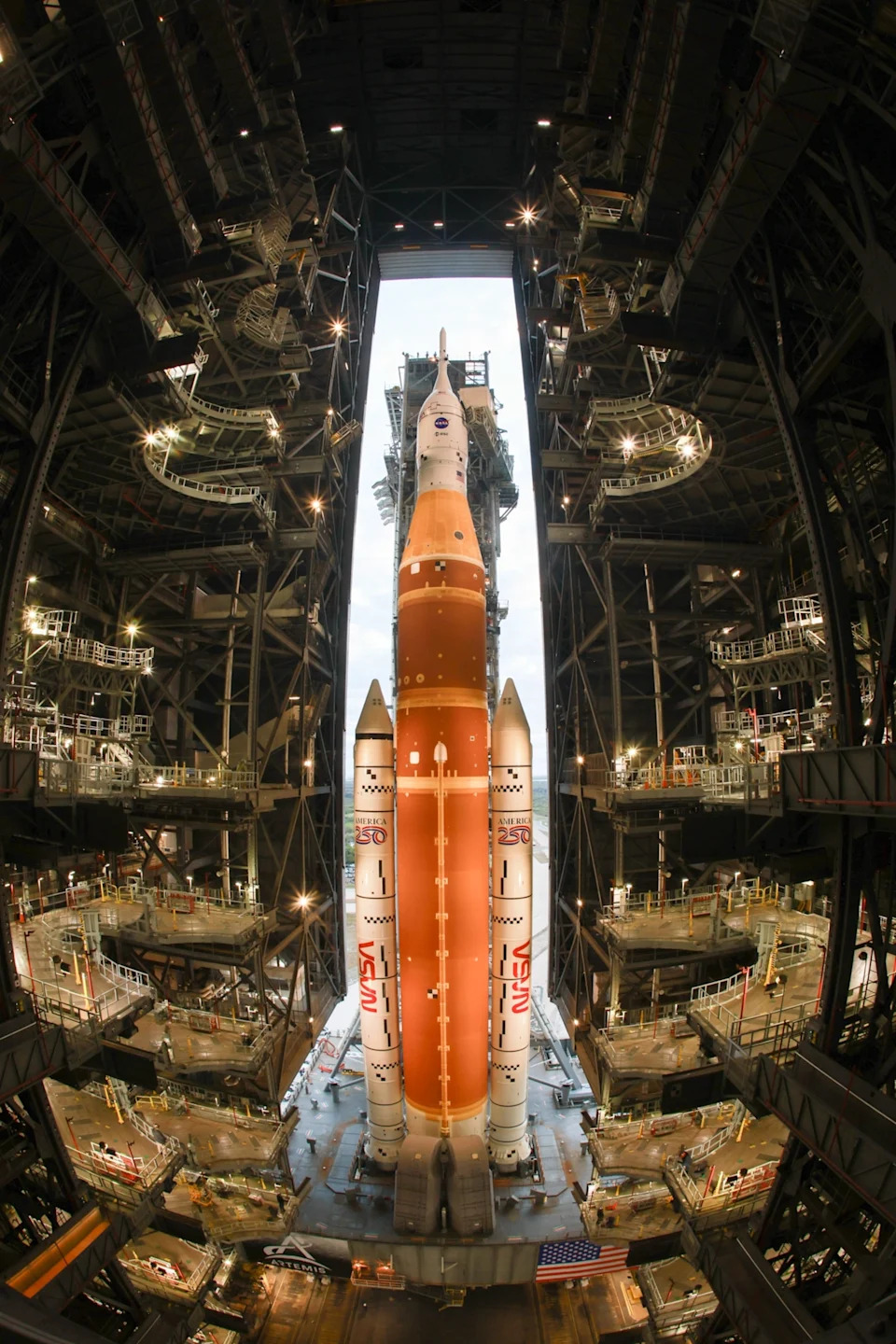

NASA paused February launch attempts for Artemis II after a wet dress rehearsal exposed multiple problems, most notably liquid hydrogen leaks during tanking. Pending repairs, the agency now says the earliest possible launch date for Artemis II is March 6, 2026.

What Happened During the Dress Rehearsal

During the rehearsal teams reported intermittent communications, cameras affected by cold, a pressurization-valve issue on the crew capsule hatch, and—most importantly—liquid hydrogen leaks while loading propellant into the Space Launch System (SLS). Launch director Charlie Blackwell-Thompson said the day was productive overall but that engineers would "figure it out" for the remaining issues.

Why Hydrogen Leaks Keep Reappearing

Hydrogen is a challenging propellant to handle. It is the smallest molecule and can seep through microscopic gaps. It must be stored at extremely low temperatures (about -423°F / -253°C) to remain liquid, and those cryogenic temperatures change material properties and can degrade seals, increasing leak risk. Artemis I experienced similar leaks in 2022, and teams reused mitigation techniques from that campaign during the recent test.

Fueling Dynamics Make It Worse

After fueling, super-cold hydrogen warms and boils off, so ground teams continuously top off the tanks. That replenishment can change pressure and temperature conditions and sometimes increases leak rates, as happened when the rehearsal was called off at T−5 minutes.

Legacy Design Choices and Costs

SLS uses RS-25 engines derived from the Space Shuttle program, which run on liquid hydrogen. When Congress authorized SLS in 2010 it required use of shuttle-era technology, which constrained engine and propellant choices. Three of Artemis II's four RS-25 engines are previously flown shuttle engines and one is new. The NASA Office of the Inspector General has estimated SLS costs at roughly $4.2 billion per launch.

What Comes Next

Teams must locate the leaking seal and perform delicate repairs while the rocket remains on the pad, using pad-side procedures refined during Artemis I to avoid rolling SLS back to the assembly building. After repairs, NASA will run another wet dress rehearsal and must complete it successfully before clearing Artemis II to fly.

Bottom line: Even though SLS is built from legacy shuttle components, it has flown only once. The program is still learning operational details—especially how to manage cryogenic hydrogen reliably at scale.

Help us improve.