Aerial lidar — airborne laser mapping — can rapidly reveal archaeological features beneath dense forest canopy, but its use over Indigenous lands raises ethical concerns when local consent is bypassed. A high-profile lidar-driven “discovery” in Honduras sidelined Miskitu presence and led to calls for prior, free and informed consultation. In contrast, a collaborative project in Metzabok, Chiapas shows how researchers can secure ongoing, culturally sensitive consent through community deliberation. The author urges lidar projects to prioritize transparency, Indigenous agency and the right to withdraw consent.

Aerial Lidar Reveals Hidden Archaeology — But Risks Erasing Indigenous Rights and Knowledge

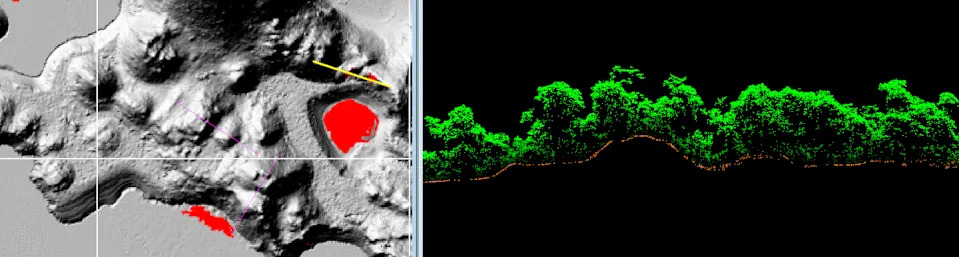

Picture a plane roaring over a tropical forest, firing millions of laser pulses per second to map the ground beneath a dense canopy. In days, researchers can produce highly detailed models across thousands of square miles. What once sounded like science fiction is now routine: aerial lidar (light detection and ranging) is transforming archaeological survey.

The Promise of Aerial Lidar

Lidar measures distance by timing laser pulses as they bounce back from the Earth’s surface. When enough pulses penetrate canopy gaps and return with measurable energy, analysts can reconstruct the ground in fine detail. That capability has generated a surge of research and even proposals to laser-map much of Earth’s landmass.

Ethical Concerns: Speed Versus Consent

Rapid mapping raises urgent ethical questions. To conduct an aerial survey researchers often need permissions at the national level — not from local communities or descendant groups. That means scans can proceed without the knowledge or consent of people who live on or claim the land, much like a satellite or mapping plane can photograph private property without each resident’s approval.

When lidar is used over Indigenous territories and ancestral burial grounds, it can function as a form of surveillance that enables outsiders to extract artifacts, cultural information and knowledge about the dead. These dynamics echo long-standing colonial patterns of dispossession and objectification.

La Mosquitia: A High-Profile Controversy

A 2015 National Geographic report by Douglas Preston publicized lidar work in Honduras’s La Mosquitia and framed it as a “discovery” of a so-called "lost city" often called Ciudad Blanca. The coverage described the mapped region as “remote and uninhabited,” language that many argued erased the longstanding presence and expertise of the Miskitu people, who have always known about sites in their territory.

“We [MASTA] demand the application of international agreements/documents related to the prior, free, and informed consultation process in the Muskitia, in order to formalize the protection and conservation model proposed by the Indigenous People.” — MASTA (translation)

After the media attention, the expedition — which the research team says held required permits — removed artifacts from the area. Miskitu representatives called for prior, free and informed consultation under international standards; their demands appear to have been largely unheeded. The episode underscores how discovery narratives and aerial surveys can facilitate dispossession even when operating within national permit systems.

A Collaborative Example: Metzabok, Chiapas

Contrast that controversy with a collaborative approach taken in Puerto Bello Metzabok, Chiapas. As part of the Mensabak Archaeological Project, researchers partnered with the Hach Winik people (commonly called Lacandon Maya) to design a culturally sensitive process of informed consent before any aerial lidar survey.

The team began with remote conversations, then met in person when the community convened an asamblea — a public forum where residents deliberate on matters affecting the community. Presentations used accessible images and a mix of Spanish and Hach T’an. The researchers explained potential benefits (territory documentation, possible sustainable tourism) and risks (increased looting or unwanted attention if data are publicized).

Community members debated the trade-offs and ultimately granted formal, ongoing consent while retaining the right to withdraw permission at any time. The project was built on long-term relationship-building, local language engagement and respect for communal land governance (Metzabok is part of a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve and is communally held under agreements with the Mexican government).

A Path Forward

Lidar need not be inherently extractive. When projects prioritize transparency, cultural sensitivity and meaningful consultation, Indigenous communities can become active collaborators rather than passive subjects. Researchers should adopt informed-consent protocols that are culturally appropriate, include clear discussions of risks and benefits, and recognize the right to refuse or retract consent.

International frameworks — including the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and ILO Convention 169 — already call for prior, free and informed consultation. Incorporating these principles into lidar research standards would align cutting-edge science with Indigenous rights and priorities.

Conclusion

The real challenge is not whether we can map faster or at higher resolution, but whether researchers will do so justly — with accountability to the peoples whose lands and ancestors are studied. Done right, aerial lidar can help document and protect heritage; done poorly, it risks reproducing colonial harms.

Editor’s note: This story was updated to reflect that the La Mosquitia team said it received all required permits.

Author: Christopher Hernandez, Loyola University Chicago. Funding for lidar work in Puerto Bello Metzabok was provided by the National Science Foundation (grant SPRF 1715009). This article was first published by The Conversation.

Help us improve.