The article examines how aerial lidar—a fast, high-resolution remote-sensing technology—is transforming archaeological survey while raising ethical concerns when used over Indigenous lands without local consent. It highlights the 2015 La Mosquitia controversy in Honduras as an example of media-driven discovery that ignored Miskitu knowledge and led to artifact removal without consultation. Drawing on collaborative work with the Hach Winik people in Puerto Bello Metzabok, the article outlines a model of culturally sensitive, ongoing informed consent and recommends transparency, shared governance, and adherence to international Indigenous rights frameworks.

Aerial Lidar in Archaeology: Mapping Power vs. Indigenous Rights — How Consent Can Change the Technology's Impact

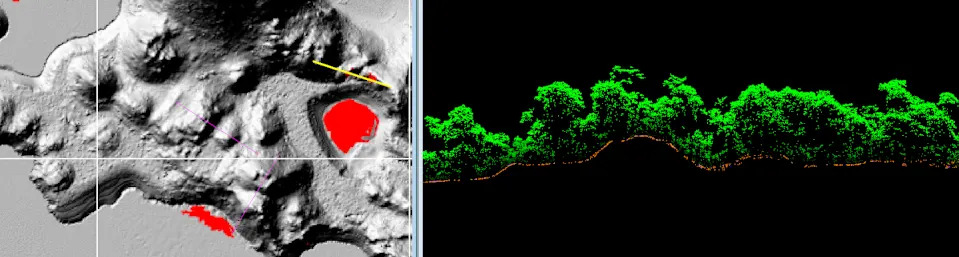

Picture a plane streaking across the sky at high speed, emitting millions of laser pulses into a dense tropical forest. The aim: to map thousands of square miles, including the ground beneath the canopy, with unprecedented detail in a matter of days.

What Lidar Does—and Why It Matters

Aerial lidar (light detection and ranging) is a remote-sensing method that uses laser pulses to measure distance. Airborne systems fire millions of pulses per second from a moving aircraft; when enough pulses find gaps in the canopy and reflect from the ground, software can reconstruct detailed surface models. For archaeologists, lidar has rapidly become a revolutionary way to locate and document landscape-scale features that were previously hidden by vegetation.

Ethical Concerns: Speed, Scale, and Consent

Because lidar surveys can be authorized at the national level, researchers can often scan territory without seeking consent from local communities or descendant groups. That legal permissibility can resemble how companies photograph private property from public airspace: technically permissible but socially fraught.

When lidar is used over Indigenous lands or places containing ancestral remains, it can become a tool of surveillance and extraction. Remote detection can enable outsiders to find sites, publicize them, and—without community approval—remove artifacts or appropriate knowledge. These harms echo longer histories of colonial appropriation and dispossession.

Case Study: La Mosquitia, Honduras

A widely publicized 2015 National Geographic report by Douglas Preston boosted global attention on lidar work in La Mosquitia. The story framed a mapped settlement as a "lost city" — language that painted the landscape as "remote and uninhabited" and ignored the lived knowledge of local Miskitu communities who have long known these places. Media hype subsequently accompanied an expedition that removed artifacts without meaningful consultation with Indigenous groups.

MASTA (Mosquitia Asla Takanka — Unity of La Moskitia) demanded that international standards for prior, free, and informed consultation be applied in the region to protect Indigenous conservation models.

The La Mosquitia episode exemplifies how technological discovery narratives can erase Indigenous presence and accelerate dispossession rather than protect heritage.

A Collaborative Alternative: Puerto Bello Metzabok

Despite these dilemmas, lidar can be deployed responsibly. Through the Mensabak Archaeological Project, the author collaborated with the Hach Winik people (often called Lacandon Maya) in Puerto Bello Metzabok, Chiapas, Mexico, to develop a culturally sensitive, community-centered approach to aerial mapping.

Metzabok lies in a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve and is communally held by the Hach Winik under agreements with Mexico's federal government. From the community’s perspective, the forest is a living entity, not an objectified resource. Guided by that worldview, the project instituted an informed-consent process tailored to local culture and governance.

Key steps included an initial WhatsApp conversation with the community leader (the Comisario), an in-person meeting, and a public asamblea where researchers explained methods, benefits, and risks in Spanish and Hach T'an. Local collaborators helped produce accessible visuals; team members who speak Hach T'an participated in the discussion. The community asked questions about the potential for looting and media attention, weighed benefits such as improved territorial documentation and responsible tourism, and ultimately gave formal consent. Importantly, consent was treated as ongoing and revocable.

Recommendations and Path Forward

To reconcile aerial lidar's scientific benefits with Indigenous rights, researchers and institutions should adopt these practices:

- Prior, Free, and Informed Consent: Seek meaningful, culturally appropriate consent from Indigenous communities and descendant groups before surveying.

- Ongoing Decision-Making: Treat consent as an ongoing process; respect community requests to pause or stop work.

- Transparency and Capacity-Building: Share data access policies, co-develop research goals, and support community stewardship and training.

- Data Governance: Protect sensitive site locations; consult communities on whether, how, and when mapping results are publicized.

- Follow International Standards: Align practice with frameworks such as the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and ILO Convention 169.

When grounded in dialogue, respect, and accountability, aerial lidar can support Indigenous autonomy rather than undermine it. The challenge for archaeology is not only mapping faster or in higher resolution, but doing so in ways that are just, humane, and responsive to the peoples whose lands and ancestors are studied.

Author And Funding

This piece is republished from The Conversation. It was written by Christopher Hernandez, Loyola University Chicago. The lidar work in Puerto Bello Metzabok received support from the National Science Foundation (Grant Number SPRF 1715009).

Help us improve.