The upcoming Artemis III mission could become the seventh crewed lunar landing, yet claims that Apollo 11 was faked persist. Practical evidence — six separate Apollo landings (1969–1972), the massive workforce involved, and technical explanations for the flag, radiation exposure, and the absence of stars — undercut hoax theories. Persistent conspiratorial belief is driven largely by long-standing mistrust in government, so rebuilding public confidence is as important as clarifying the technical facts.

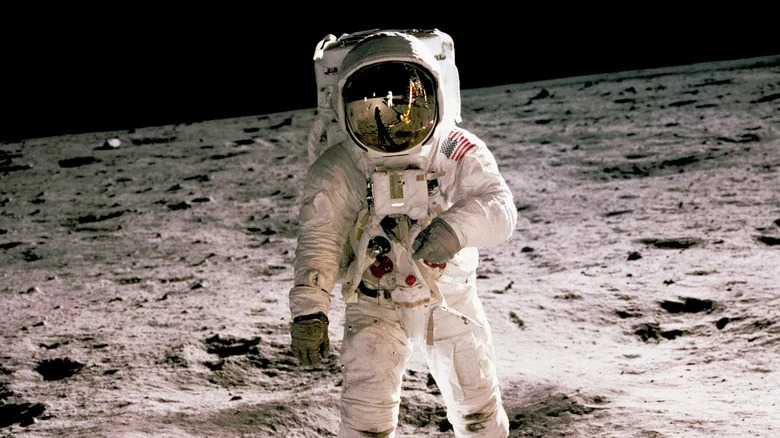

Were the Apollo Moon Photos Faked? Evidence, Myths, and Why Conspiracies Persist

If plans hold, NASA's Artemis III could land astronauts on the Moon in as little as a year, becoming only the seventh crewed mission to touch lunar soil. Yet a vocal minority still claims the original Apollo 11 mission in 1969 was staged. This article examines the technical evidence, the scale of the Apollo program, and the social reasons those doubts endure.

Why Multiple Landings Matter

One of the simplest rebuttals to the “one big hoax” idea is that Apollo didn’t stop at a single landing. There were six crewed lunar landings between 1969 and 1972. If the goal had been only a symbolic victory over the Soviet Union, it would be difficult to explain why the United States would fabricate five additional missions in rapid succession.

The Scale Of Apollo: Who Would Keep The Secret?

The Apollo program involved roughly 400,000 employees plus partnerships with more than 20,000 private contractors and university researchers. Claiming the landings were faked implies an implausibly large and sustained conspiracy across thousands of people and institutions. In practice, the logistical and technical challenge of producing convincing fake missions would likely have been greater than actually going to the Moon.

Technical Answers To Common Claims

Flag Appears To Be Waving

Critics point to photographs where the planted U.S. flag looks as if it is waving despite the Moon’s lack of atmosphere. NASA anticipated this perception: the flag had a horizontal crossbar to hold it out, and it was tightly packed for the trip, producing pronounced wrinkles. Those folds, combined with movement as astronauts handled the pole, explain the appearance without invoking wind.

Van Allen Radiation Belts

Some argue astronauts would have been fatally irradiated passing through the Van Allen belts, regions of charged particles trapped by Earth's magnetic field. NASA designed the Apollo command modules with shielding (aluminum shells and specific trajectories) to minimize exposure. The crews did receive elevated doses—roughly an order of magnitude higher than an average medical radiographer’s annual exposure—but not near acutely lethal levels.

No Stars Visible In Photos

Images and footage from the lunar surface rarely show stars. That’s a camera-exposure issue: the lunar surface and the astronauts’ suits reflected intense sunlight during lunar daytime, so cameras used fast exposures and small apertures that rendered stars invisible. This same bright, high-contrast lighting also affects how shadows appear compared with typical Earth photography.

Unusual Shadows And Lighting

Shadows in Apollo photos sometimes look odd to viewers who expect Earthlike lighting. The Moon’s surface is highly reflective, sunlight is the only light source during lunar daytime, and low-angle illumination across a rough surface creates deep, high-contrast shadows and unexpected visual cues. These are optical and environmental effects, not proof of staging.

Why These Conspiracies Persist

Technical explanations alone often fail to persuade those who already distrust official accounts. The Apollo-hoax narrative is rooted in broader public skepticism toward government institutions. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the protracted Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal severely eroded trust in U.S. government actions. Later revelations—such as MKUltra and the Iran–Contra affair—show that governments have at times concealed wrongdoing, which has a lingering impact on public confidence.

More recently, distrust has manifested in harmful behaviors and false claims, from sabotaging infrastructure to rejecting public-health guidance. These trends show how institutional mistrust can amplify and sustain fringe theories, even when strong evidence contradicts them.

Rebuilding Trust Matters

To counter persistent conspiracy theories, experts must combine clear, accessible technical explanations with honest engagement about why people doubt official narratives. Transparency, open data, and public outreach around current and future missions—like Artemis—can help restore confidence. Preserving the record of human achievement in space depends not only on scientific facts but on the public’s willingness to accept them.

Conclusion: The technical and logistical evidence strongly supports the reality of the Apollo lunar landings. Still, understanding and addressing the social and political roots of conspiracy belief is essential if future missions are to be widely accepted and celebrated.

Help us improve.