Venezuelans in Spain are responding with a mixture of hope and fear after Nicolás Maduro’s removal, reflecting diverse experiences across the expatriate community. Around 600,000 Venezuelans live in Spain, many in Madrid working in health care, hospitality and elder care. Personal accounts — a father seeking justice for a son killed in 2017, a journalist hoping her daughters might return to a democratic Venezuela, and a wife waiting for news of jailed relatives — illustrate the emotional, political and practical stakes for migrants and their families.

After Maduro’s Ouster, Venezuelans in Spain Balance Hope and Fear

MADRID — Venezuelans living in Spain are watching developments back home with a mix of hope, anxiety and cautious skepticism after U.S. forces deposed Nicolás Maduro. An estimated 600,000 Venezuelans now live in Spain — the largest Venezuelan community outside the Americas — many concentrated in Madrid and working in health care, hospitality and elder care.

Some migrants have established long-term lives in Spain; others arrived more recently fleeing political persecution, violence and economic collapse. Below are the personal perspectives of three Venezuelans in Madrid on what Maduro’s removal might mean for their families and for Venezuela’s future.

A Father Seeks Justice For His Son

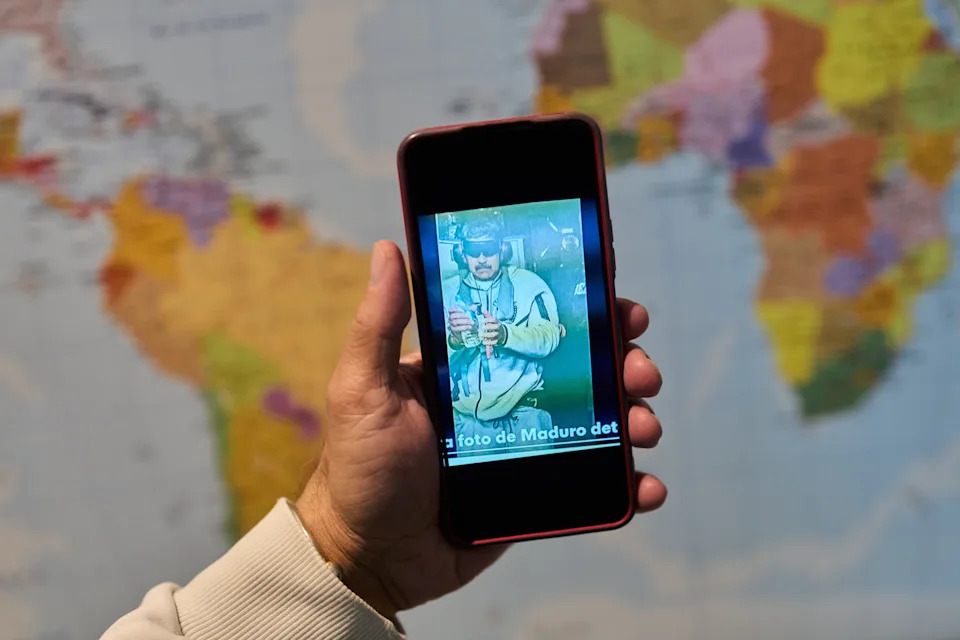

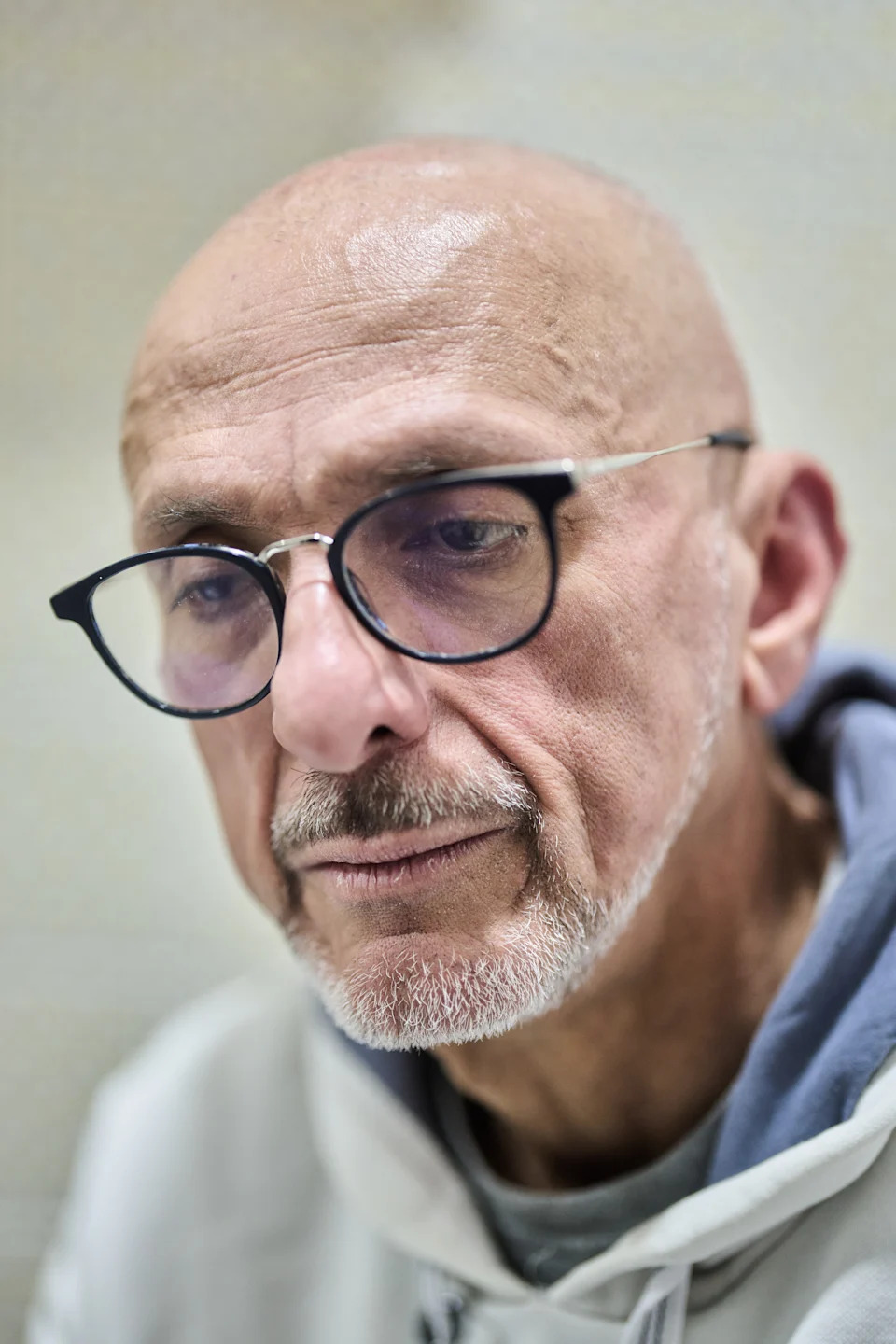

David Vallenilla, 65, woke on Jan. 3 to messages from relatives saying "they invaded Venezuela." Living alone in southern Madrid with two dachshunds and a few birds, he described his first reaction as disbelief and then an overwhelming flood of emotion.

His son, 22-year-old nursing student David José, was shot at close range by a soldier during a June 2017 protest near a Caracas military air base and later died of his injuries. Video of the shooting circulated widely, turning the killing into a symbol of the government’s repression at the time. After repeatedly demanding answers, Vallenilla received threats and relocated to Spain two years later with help from an NGO.

“Nothing will bring back my son. But the fact that some justice has begun to be served for those responsible helps me see a light at the end of the tunnel,” Vallenilla said. “I also hope for a free Venezuela.”

He says he fears renewed violence but has guarded hope that international pressure and new authorities could achieve changes Venezuelans sought through protests and institutions.

A Mother Hopes Her Daughters Can Return To A Democratic Venezuela

Journalist Carleth Morales moved to Madrid about 25 years ago, around the time Hugo Chávez won reelection under a new constitution. She originally intended to study and return home, but Venezuela’s political and economic collapse changed those plans.

In 2015 she founded an association for Venezuelan journalists in Spain, now counting hundreds of members. When Maduro was captured, Morales awoke to a stream of missed calls from friends and family.

“Of course, we hope to recover a democratic country, a free country, a country where human rights are respected,” she said. “But it’s difficult to think that as a Venezuelan when we’ve lived through so many things and suffered so much.”

Morales says she is unlikely to return permanently after more than two decades in Spain, but she hopes the next generation — her daughters — might one day see Venezuela as a viable place to live and work.

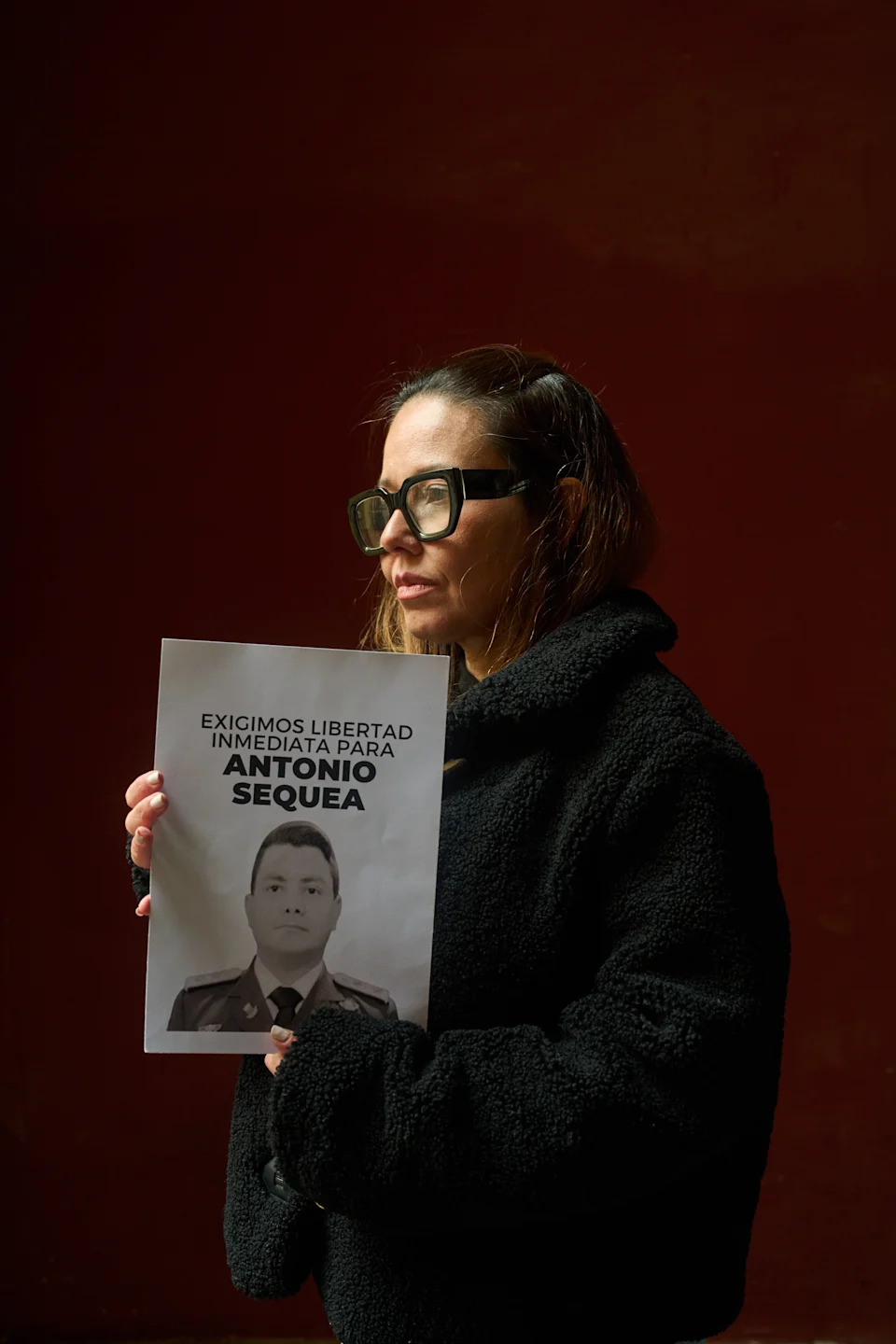

A Wife Waits For News Of Jailed Relatives

Verónica Noya has spent weeks waiting for a phone call to say that her husband and her brother have been freed. Her husband, Capt. Antonio Sequea, was imprisoned in 2020 after taking part in a military incursion aimed at ousting Maduro, and Noya says he has been held in solitary confinement at El Rodeo prison in Caracas. She also has had no contact with her brother, arrested in the same plot.

Venezuelan authorities said hundreds of political prisoners were released after Maduro’s capture, but human rights groups dispute that figure and argue the true number is far lower. Noya is anguished as she waits for news about four detained relatives, including her husband’s mother.

Having fled in haste, her family came to Spain because Noya already held a Spanish passport through family ties. Despite the uncertainty, she said she remains deeply attached to her homeland and dreams of returning to a democratic Venezuela.

Help us improve.