Venezuelans across Latin America expressed mixed reactions after their president’s removal: relief for some, deep caution for many. Nearly 7 million Venezuelan migrants and refugees live in Latin America (about 2.8 million in Colombia and 1.5 million in Peru), with roughly 1 million more in the U.S.; most are unwilling to return while Venezuela’s economy and institutions remain unstable. Political shifts in host countries and looming deportations heighten legal uncertainty and risks of criminal exploitation, making large-scale returns unlikely without clear improvements at home.

Venezuelan Diaspora Cautious After President’s Removal — Millions Remain Reluctant to Return

Almost immediately after reports that Venezuela’s president had been removed from power, officials from Washington to Lima urged some of the roughly 8 million Venezuelans who have dispersed across the Americas over the past decade to consider returning home. For many, however, the idea remains distant.

Voices From the Diaspora

In Lima’s largest textile market, 22-year-old graphic designer Yanelis Torres was busy printing T-shirts bearing images of the captured former president Nicolás Maduro with slogans such as “Game Over.” Customers snapped them up within hours of the news. But Torres, like many others, said she would not rush back: “You’ve got a lot of things here,” she said, adding that meaningful change in Venezuela would take time. “You’ve got to keep an eye on it, know what’s going on, but not lose hope.”

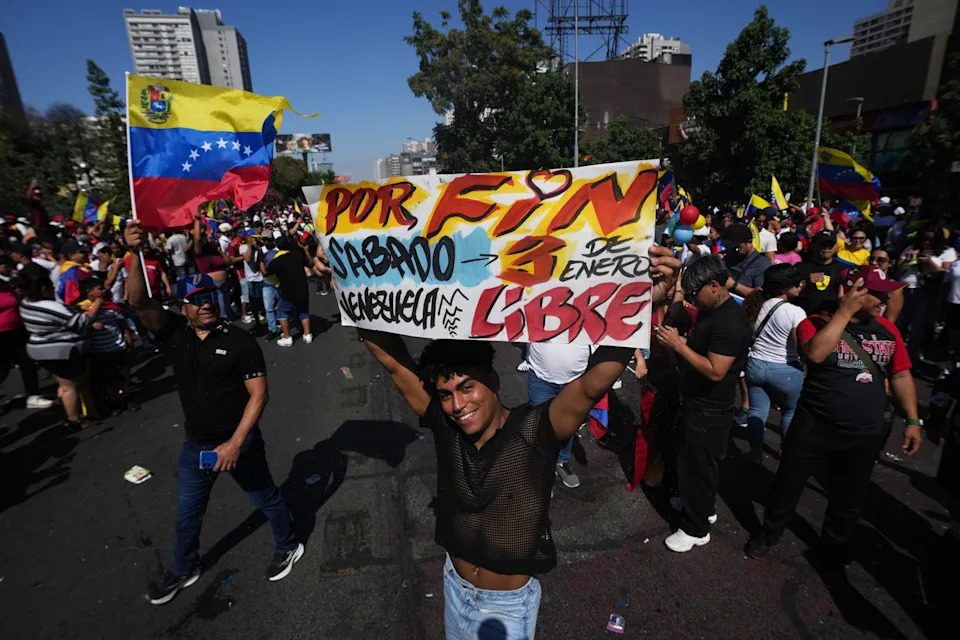

Others shared similar, guarded reactions. Some greeted the news with joy; others with skepticism or fear for family still in Venezuela. The capture prompted celebrations in neighborhoods such as Santiago’s “little Caracas,” but many Venezuelans abroad weighed the risks of returning against the reality of persistent economic collapse and a government apparatus that, apart from Maduro and his wife, remains largely intact.

Why People Fled

Venezuelans left their country in large numbers during years of deepening political and economic crises. According to R4V, nearly 7 million Venezuelan migrants and refugees live in Latin America today, with Colombia hosting about 2.8 million and Peru about 1.5 million; roughly 1 million are estimated to be in the United States. Once one of the region’s wealthiest countries, Venezuela now faces rampant poverty — an estimated eight in 10 people live below the poverty line — despite sitting on the world’s largest proven oil reserves.

Life Abroad Is Mixed

Experiences among the diaspora vary. Some migrants have found work or started small businesses; others remain undocumented, move repeatedly, or attempt perilous routes to reach the United States. Many face legal uncertainty: thousands have been deported in the past year and others may soon lose protected status in host countries.

“We’re nowhere near where we’re going to have a country where people that fled … feel that they could be comfortable returning.” — Maureen Meyer, WOLA

Stories from the field reflect this reality. Eduardo Constante, 36, described an interrupted journey across multiple countries and through the Darién Gap before reaching the U.S. border. Yohanisleska de Nazareth Márquez, traveling with her 3-year-old, was deported to Mexico and now hopes to apply for asylum there while worrying about safety and shelter conditions.

Political Headwinds in Host Countries

Political changes in destination countries are shaping migrants’ prospects. In Chile, President-elect José Antonio Kast has prioritized deporting undocumented immigrants and recently gave migrants a short window to leave or regularize their status. Peru and Colombia will also elect new leaders, and migration policy is expected to be a central debate.

Some leaders have discussed creating humanitarian corridors through Chile, Peru and Ecuador to facilitate voluntary returns, but experts caution that returns will depend on security, economic rebuilding, and credible guarantees for safe reintegration.

Risks If Returns Are Forced

Analysts warn that forced returns or mass deportations could leave migrants vulnerable to criminal networks and exploitation, especially as the smuggling business and migration routes change. Many who are returned could face food scarcity, surveillance, and repression at home.

What Would Encourage Returns?

Most Venezuelans interviewed said they need clear improvements in safety, economic opportunity, and rule of law before considering permanent return. For now, many plan to stay where they have rebuilt lives — opening businesses, working, and supporting families back home — while monitoring developments closely.

“It won’t be this year, but maybe it will be next year,” said Alexander Leal, 66, who sells homemade ice cream in Chile and hopes to return when the country is “fixed.” Others, like Uber driver Yessica Mendoza, are determined to stay: “Returning is not an option.”

Reported contributions to this story came from correspondents in Mexico City, Santiago and Quito.

Help us improve.