The Stanford study identifies the enzyme 15-PGDH as a driver of age-related cartilage loss and shows that inhibiting it restores cartilage thickness in older mice and prevents osteoarthritis after simulated ACL injury in young mice. Human knee cartilage samples exposed to the inhibitor also showed signs of regeneration. The treatment appears to work by reprogramming resident chondrocytes rather than relying on stem cells; clinical trials are the next step.

Blocking One Protein Restores Cartilage in Mice — A Promising Path Toward Osteoarthritis Treatments

A Stanford University team has traced age-related cartilage loss to a single protein and shown in mice that blocking it can restore cartilage and protect joints after injury. The findings, published in the journal Science, point to a potential new strategy for treating osteoarthritis and age-related joint degeneration.

What the researchers found

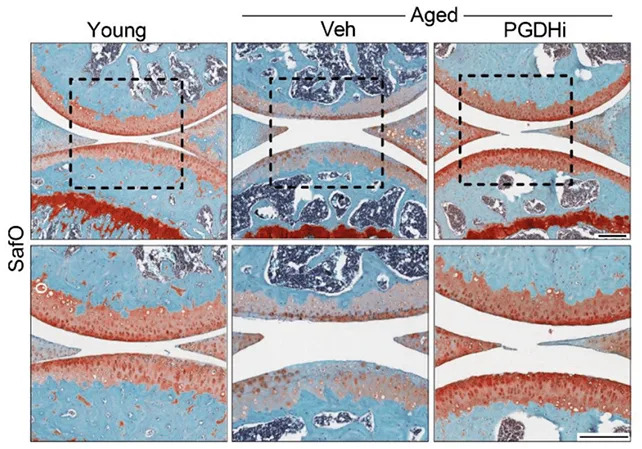

The protein 15-PGDH increases with age and interferes with molecules that normally repair tissue and control inflammation. In experiments, older mice that received a 15-PGDH inhibitor regained knee cartilage thickness. In young mice with surgically induced injuries that mimic an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture, the same treatment prevented the development of osteoarthritis that would otherwise occur in this model.

How regeneration appears to work

Earlier approaches to cartilage repair often focused on stem cells. In these experiments, regeneration occurred without adding stem cells: resident chondrocytes — the cells that make and maintain cartilage — changed their gene-expression patterns and shifted into a healthier, more reparative state when 15-PGDH was inhibited.

“This is a new way of regenerating adult tissue, and it has significant clinical promise for treating arthritis due to aging or injury,” said microbiologist Helen Blau, noting that the team found resident cells — not stem cells — were responsible for the effect.

Functional effects and human tissue tests

Treated mice showed functional improvement: a steadier gait and greater weight-bearing on previously injured legs, consistent with reduced pain and better joint function. The team also exposed human cartilage samples taken during knee replacement surgery to the inhibitor; those samples showed signs of regeneration, including increased stiffness and reduced inflammatory markers.

“The mechanism is quite striking and really shifted our perspective about how tissue regeneration can occur,” said orthopaedic scientist Nidhi Bhutani. “A large pool of existing cartilage cells appear capable of changing their gene expression and supporting repair.”

What this means and next steps

Although results in mice and ex vivo human tissue are promising, translation to safe and effective therapies for people will require clinical trials. A prior human study of a 15-PGDH blocker aimed at treating muscle weakness reported no major safety concerns, which could help accelerate testing for joint repair. Researchers emphasize the need to determine optimal dosing, delivery method, long-term effects and whether the benefits seen in mice replicate in humans.

Bottom line: Blocking 15-PGDH offers a compelling new approach that reprograms existing cartilage cells to repair tissue, reduce inflammation and improve function in preclinical models. If confirmed in clinical trials, the strategy could eventually reduce pain and the need for hip and knee replacements, but human efficacy and safety remain to be demonstrated.

Help us improve.