USAID's effective dismantling threatens global lives and American interests. The agency, operating for 63 years on less than 1% of the federal budget, funded seed research, disease surveillance and famine forecasting that protected U.S. food supplies and public health. Estimates link aid disruptions to hundreds of thousands of deaths and project millions more by 2030. The authors urge Congress to re-establish an independent, cabinet-level Department for International Aid to restore these security-critical functions.

What the U.S. Lost When USAID Was Dismantled: Food, Health Surveillance and National Security at Risk

The start of a new year is an opportunity to reflect — and to correct the mistakes of the past. Few recent decisions may carry greater long-term consequences for American health, safety and prosperity than the effective dismantling of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).

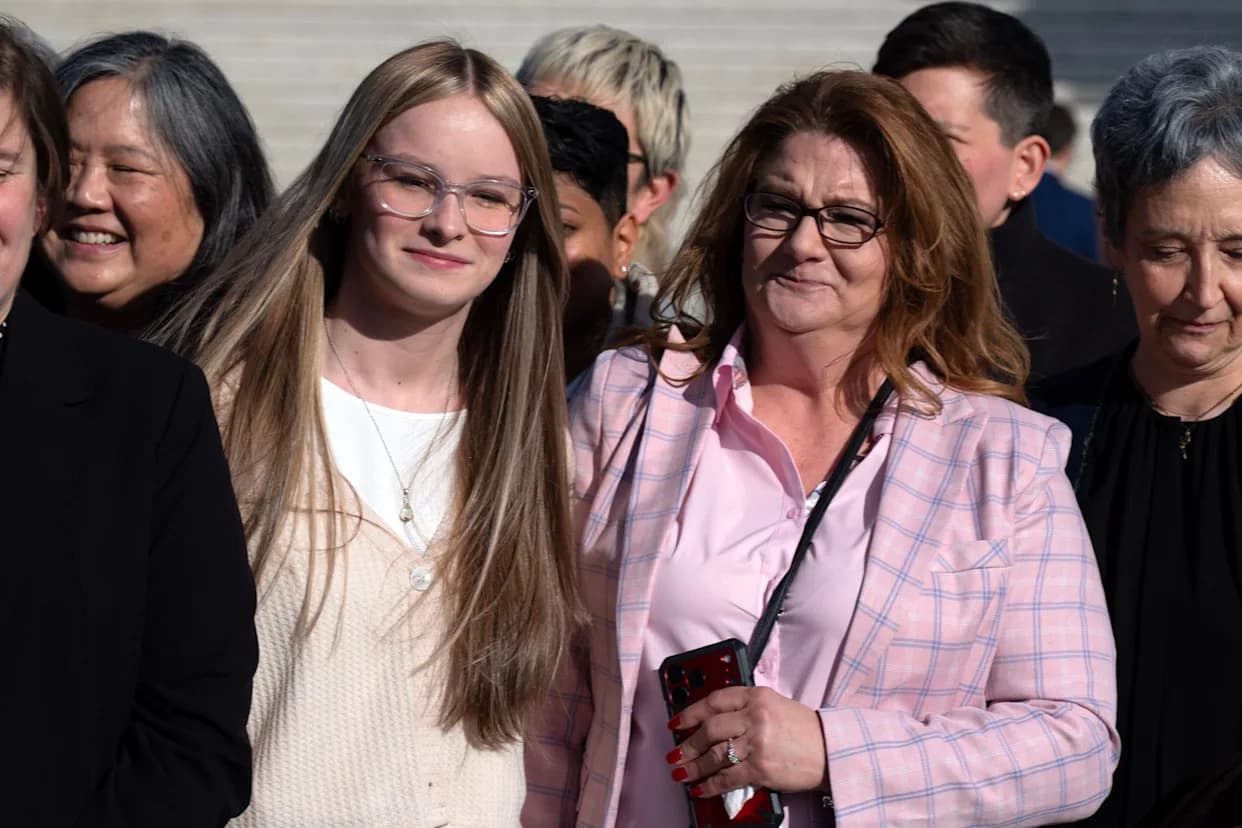

The Trump administration took many contentious actions, but the erosion of USAID stands out for its potential to inflict lasting harm. As White House Chief of Staff Susan Wiles observed, "I think anybody that pays attention to government and has ever paid attention to USAID believed, as I did, that they do very good work." We write from direct experience: one of us led USAID under a Democratic administration and the other under a Republican administration.

Small Budget, Large Returns

For 63 years USAID enjoyed bipartisan backing and operated on less than 1% of the federal budget, yet it delivered substantial, often unseen benefits. Conservative estimates suggest that more than 700,000 people in developing countries died last year following aid disruptions, about two-thirds of them children. A widely cited Lancet analysis projects that nearly 14 million people could die by 2030 if current trends continue — figures that should alarm any nation that depends on global stability and public-health surveillance.

Protecting Food Supplies

One underappreciated service USAID provided was funding agricultural research that protected global — and American — food supplies. Two decades ago, wheat rust threatened nearly 90% of wheat cultivars worldwide. USAID funding, alongside other donors, supported the development of rust-resistant wheat varieties.

USAID historically provided nearly 40% of the budget for the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center, the research hub that produced these resistant seeds and helped institutionalize the Green Revolution. Those seed advances helped safeguard the global wheat harvest and also benefited American farmers. When USAID funding was disrupted, that support ended — with tangible risks to future crop resilience.

Sorghum, Striga, and American Ranchers

USAID-backed research also tackled Striga ("witchweed"), a parasitic plant that once threatened the world’s sorghum crop. Sorghum is an important human food in parts of Africa and Asia and a critical cattle feed in drier regions of the United States; the U.S. is the world’s largest sorghum producer (valued at over $1 billion annually).

Dr. Gebisa Ejeta, whose work was financed by USAID and who now teaches at Purdue University, developed a Striga-resistant sorghum variety that halted the weed’s spread. His breakthrough was significant enough that American cattle ranchers traveled to Washington to thank USAID — a clear example of how foreign agricultural research can yield domestic dividends.

Early Warning For Disease And Famine

Beginning in the Reagan administration and for roughly 40 years, USAID designed and managed the Demographic and Health Surveys Program, a statistics and surveillance system operating in about 90 developing countries. The program tracked death rates, birth rates, disease incidence and emerging outbreaks — functioning as an early-warning network for novel pathogens.

The dismantling of USAID weakened that global surveillance capability. Once a pathogen is widespread internationally, border controls are insufficient; early detection and response abroad matter for U.S. health security. Similarly, USAID created the Famine Early Warning System, which combined satellite monitoring and ground reporting to forecast food crises. When that system signaled a drought in East Africa threatening roughly 20 million people, it enabled a coordinated global response under President Clinton that averted mass starvation and saved millions of lives.

Why Absorption Into State Is Not The Answer

Like any agency, USAID needed constructive reform: it faced heavy congressional earmarks and operational constraints. But moving the remaining foreign-assistance functions into the State Department risks mission conflict and shorter planning horizons. The State Department is primarily a policy and diplomatic organization focused on near-term decisions, while USAID was structured as a program-management agency that executes multi-year development projects and sustains international supply chains with five- to ten-year time horizons.

A Way Forward

Recent shifts in congressional dynamics may create an opening for corrective action. Congress should consider reconstituting USAID as a cabinet-level U.S. Department for International Aid, consolidating foreign-assistance programs currently scattered across roughly a dozen departments and agencies. An independent department would restore development assistance to its rightful place in the U.S. national-security architecture and revive vital functions that protect American food supplies, public health and global stability.

Authors: J. Brian Atwood served as USAID administrator during the Clinton administration. Andrew S. Natsios served as USAID administrator during the George W. Bush administration and is the author of the forthcoming book "Guns Are Not Enough: Foreign Aid in the National Interest."

Help us improve.