Modern microbialites—rocklike structures built by mineralizing microbes—are alive and productive. Fossils date back 3.7–3.5 billion years, and new measurements from South Africa show these formations can sequester up to ~3 lb (≈1.4 kg) of CO2 per square foot per year. Researchers also observed substantial nighttime carbon uptake, indicating nonphotosynthetic metabolisms. The findings, published in Nature Communications, highlight microbialites’ role in Earth’s early oxygenation and their potential relevance to natural carbon sequestration today.

These 'Living Rocks' Are Thriving — Ancient Microbialites Rapidly Lock Away Carbon

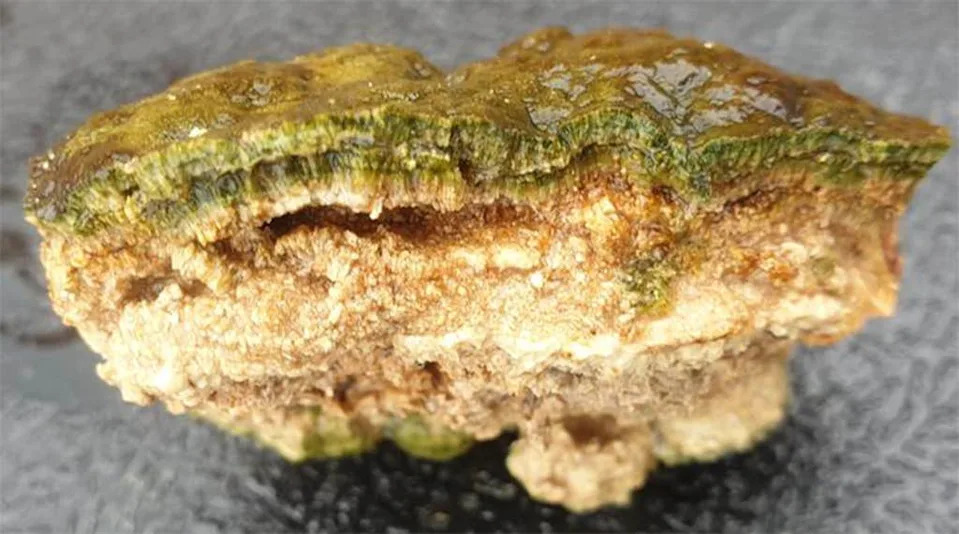

You might think you're looking at patches of mossy stone, but these mounds are actually living communities—some of the planet’s oldest organisms—and they’re thriving in harsh coastal waters.

What Are Microbialites?

Microbialites are rocklike structures formed when communities of microbes extract dissolved minerals from water and precipitate them into hard, layered formations. Fossil microbialites have been dated to roughly 3.7–3.5 billion years ago, making them strong candidates for some of Earth’s earliest life.

Why They Matter

About a billion years after those earliest microbialites appeared, photosynthesizing cyanobacteria that built similar structures are thought to have injected oxygen into Earth’s oceans and atmosphere, a fundamental shift that enabled the later rise of oxygen-adapted life. Today, living microbialites persist in diverse aquatic settings—from the hypersaline Shark Bay in Australia to freshwater lakes in Canada and calcium-rich coastal seep zones in South Africa.

New Findings From South Africa

An international team studied modern microbialites along South Africa’s southeastern coast, where calcium-rich water seeps from coastal sand dunes and creates demanding conditions for life. Their work, published in Nature Communications, shows these formations are far from inert fossils: they grow rapidly in hostile environments and capture substantial carbon.

The researchers measured carbon uptake equivalent to up to about 3 pounds (≈1.4 kg) of CO2 per square foot per year. To visualize that rate, an area the size of a tennis court could sequester as much CO2 annually as roughly three acres of forest, according to the study's comparisons.

"These ancient formations that the textbooks say are nearly extinct are alive and, in some cases, thriving in places you would not expect organisms to survive," said Rachel Sipler, a marine biogeochemist at the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences.

Surprising Nighttime Activity

Unexpectedly, the team found microbialites absorbed roughly as much carbon at night as during daylight hours. That pattern indicates microbes in the structures use metabolic pathways beyond photosynthesis—processes that allow carbon uptake in the dark, analogous to metabolisms observed in deep-sea vent communities.

Implications

These living rocks illuminate both Earth's early biological and geochemical history and present-day natural mechanisms for carbon sequestration. While more research is needed to quantify global potential, microbialites offer a model for robust, low-tech carbon capture that operates in extreme environments.

Bottom line: Microbialites are not only ancient relics but active, productive ecosystems that can rapidly mineralize carbon—even at night—making them important to studies of early life, long-term carbon cycling, and potential natural carbon sinks.