NASA's Parker Solar Probe recorded detailed images of a coronal mass ejection on Dec. 24, 2024, showing portions of the ejected plasma reversing direction and falling back toward the Sun. The footage reveals magnetic field lines snapping and reconnecting into loops that drive these "inflows." For the first time, scientists measured the speed and size of the returning blobs and are using the data to refine space weather models, improving forecasts of CME paths and impacts across the solar system.

Parker Solar Probe Sees Solar Wind 'U‑Turn' — Close‑Up Images Show Plasma Falling Back Toward the Sun

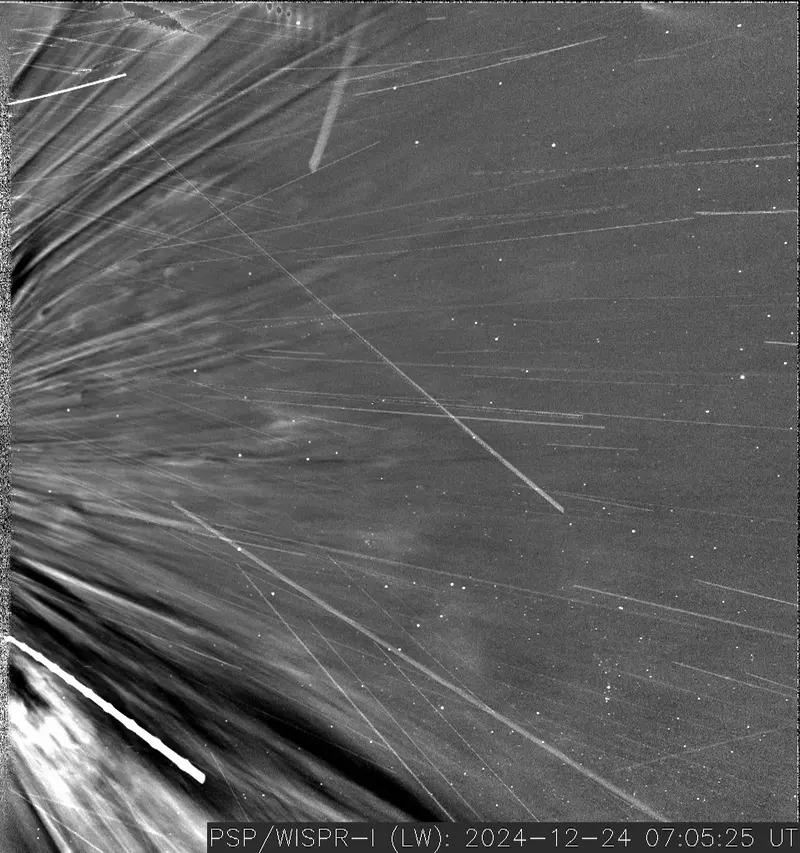

NASA's Parker Solar Probe has captured the clearest close‑up images yet of solar material erupting from the Sun and then reversing course to fall back along reconnected magnetic loops. The observations — taken during Parker's record close approach on Christmas Eve 2024 — reveal how the Sun recycles magnetic energy and how those processes can reshape the magnetic environment that guides future solar storms.

What Parker Saw

During the Dec. 24, 2024 flyby, when Parker passed roughly 3.8 million miles (6.1 million kilometers) above the solar surface, its WISPR camera recorded a coronal mass ejection (CME): a bright, superheated blob of plasma blasting outward. In a stitched sequence of images, the ejected cloud is seen coasting away before thinning and, in places, curling back toward the Sun.

Magnetic Reconnection and Inflows

Scientists say nearby magnetic field lines, stretched by the eruption, snapped and rapidly reconnected into giant loops. Some of those loops continued outward, while others contracted and pulled streams of plasma back toward the Sun in a process called inflows. As this returning material falls, it interacts with and reshapes magnetic fields near the solar surface — changes that can alter the trajectories of subsequent CMEs.

"We've previously seen hints that material can fall back into the Sun this way, but to see it with this clarity is amazing," said Nour Rawafi, Parker Solar Probe project scientist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory.

"That's enough to be the difference between a CME crashing into Mars versus sweeping by the planet with no or little effects," said Angelos Vourlidas, the WISPR project scientist and a researcher at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory.

Measurements and Space Weather Impact

Because Parker was unusually close, scientists were able to directly measure the speed and size of the blobs falling back toward the Sun for the first time. Those measurements are already being used to refine models of the Sun's complex magnetic environment and to improve predictions of space weather across the solar system. Better modeling of these reconnection-driven inflows could extend advance warnings for geomagnetic storms that can affect satellites, communications, power grids and produce dramatic auroras.

Why It Matters: Understanding how CMEs and their associated magnetic fields evolve and reconnect helps forecasters predict whether an eruption will hit a planet or pass harmlessly by — a distinction with real operational consequences for spacecraft and ground systems throughout the solar system.