A University of Tokyo study published in Nature finds that when melanocyte stem cells sustain severe DNA damage they often differentiate and are lost, causing gray hair but removing cells that could become melanoma. Exposure to carcinogens like UVB or DMBA can instead trigger survival pathways and increased KIT ligand release, allowing damaged stem cells to persist and become more likely to turn cancerous. The research reframes graying as a potential anti‑cancer mechanism and warns that preventing gray hair without caution could raise melanoma risk. Future work will test how these findings translate to humans and whether therapies can safely tune stem‑cell responses.

Gray Hair May Be the Body’s Built‑in Defense Against Melanoma, Study Finds

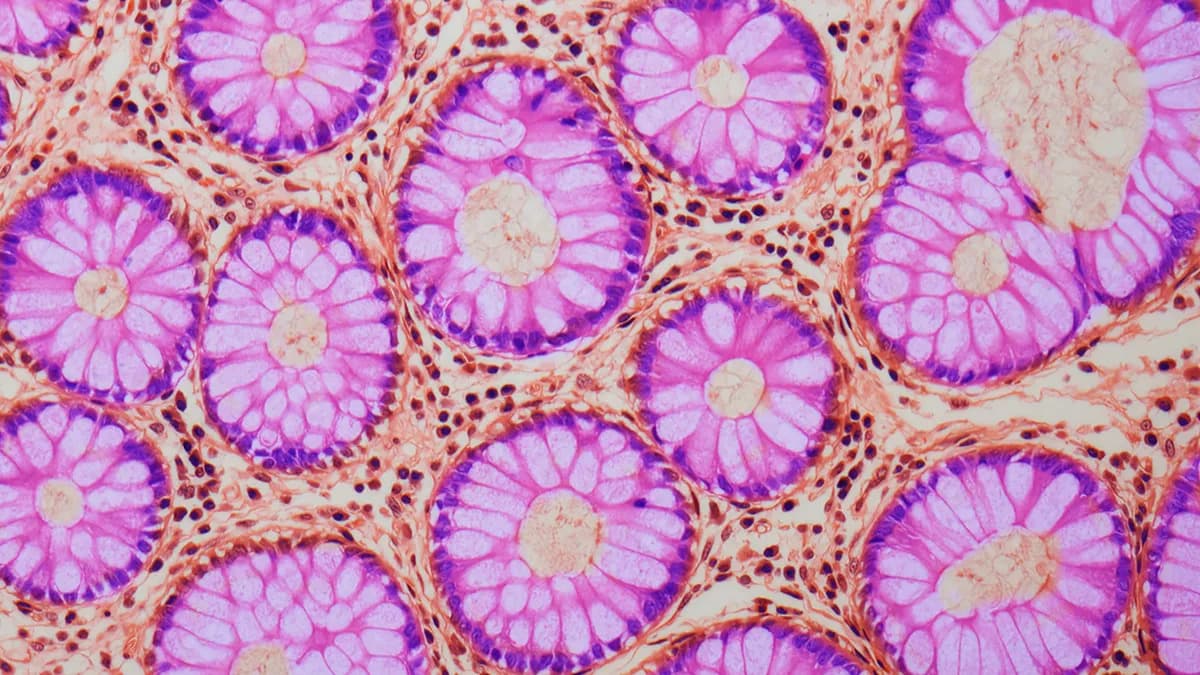

A new study from researchers at the University of Tokyo suggests that graying hair can be an active, protective response that reduces the risk of melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer. The work, led by Professor Emi Nishimura and Assistant Professor Yasuaki Mohri and published in the journal Nature, identifies how pigment-producing stem cells in hair follicles respond differently depending on the type of DNA damage and signals from surrounding tissue.

In mouse experiments, severe genomic injuries such as double‑strand DNA breaks activated a pathway involving p53 and p21 that triggers senescence‑coupled differentiation. Damaged melanocyte stem cells stopped self‑renewing, matured into pigment cells and were ultimately lost. The result: visible graying but a smaller pool of potentially cancerous stem cells.

By contrast, exposure to carcinogens such as UVB light or the chemical DMBA altered that outcome. Injured stem cells engaged survival programs linked to arachidonic acid metabolism, and nearby skin cells released higher levels of the KIT ligand (KITL). Those signals allowed the damaged stem cells to persist and continue dividing, preserving hair color but markedly increasing the likelihood that the cells could progress to melanoma.

Live imaging of mouse hair follicles confirmed this shift: radiation that normally caused rapid stem‑cell loss and premature graying had little effect when carcinogens were present. As Professor Nishimura summarized, "The same stem cell population can follow antagonistic fates — exhaustion or expansion — depending on the type of stress and microenvironmental signals."

Implications

The findings reframe graying as more than cosmetic aging: it can reflect a deliberate cellular decision that removes damaged cells and lowers cancer risk. They also raise important cautions for efforts to prevent or reverse gray hair. Interventions that keep melanocyte stem cells active longer might inadvertently increase melanoma risk if they block protective stem‑cell loss. Conversely, therapies that promote safe, controlled removal of damaged pigment stem cells could offer a novel approach to reducing skin cancer risk.

Caveats and next steps

These results come from animal models and focused molecular studies. While the mechanisms identified are biologically plausible and reported in Nature, further research is needed to confirm how directly these processes translate to humans and to develop safe clinical strategies. The Tokyo team suggests future work could aim to precisely tune stem‑cell responses to damage so that visible signs of aging are addressed without increasing cancer risk.

Study citation: Emi Nishimura and Yasuaki Mohri et al., published in Nature.

Help us improve.