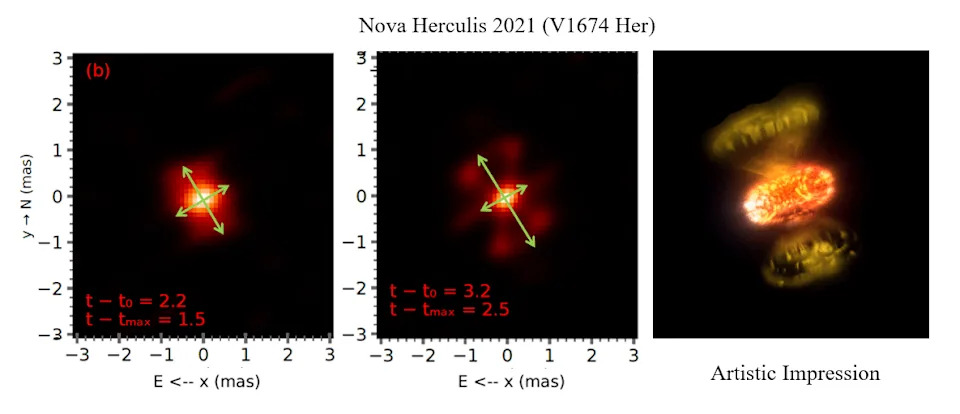

Interferometric images from the CHARA Array, supplemented by Fermi and Gemini observations, captured two novae in unprecedented detail. V1674 Herculis was an extremely fast nova with dual gas outflows and gamma-ray emission, while V1405 Cassiopeiae evolved over ~50 days into a rare common envelope before producing its own gamma-ray flash. Together, the observations link surface nuclear burning, ejecta geometry, and high-energy radiation.

Stunning Interferometric Images Reveal Two Novae Erupting — Gamma Rays and a Rare Common Envelope

A pair of high-resolution interferometric images from the CHARA Array, combined with observations from NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope and the Gemini Observatory, have revealed the earliest and most detailed views yet of two stellar explosions called novae. These observations expose the complex geometry and energetic processes that unfold in the first days and weeks after a thermonuclear surface explosion on a white dwarf.

What Is a Nova? A nova occurs when a white dwarf — the dense remnant of a Sun-like star — accretes hydrogen-rich material from a close companion. As that material piles up on the white dwarf’s surface, it can ignite in a thermonuclear runaway that dramatically brightens the system. Unlike a supernova, the white dwarf typically survives the outburst. The energy released in some novae can be comparable to the Sun’s output over roughly 100,000 years, but emitted in a matter of moments.

Historically, the earliest stages of novae were difficult to resolve because the ejecta appeared as an unresolved point of light. Using interferometry — a technique that combines light from widely separated telescopes to achieve extremely fine angular resolution — astronomers can now reconstruct the shape and evolution of the expanding material.

Two Very Different Novae

V1674 Herculis was one of the fastest novae on record: it rose to peak brightness and faded within just a few days. Interferometric imaging reveals two distinct gas outflows, indicating multiple powerful ejections that interacted with one another. High-energy gamma rays from this event were detected by NASA’s Fermi telescope, showing that even these relatively common stellar explosions can produce some of the most energetic radiation in the universe.

V1405 Cassiopeiae evolved much more slowly. Over a period exceeding fifty days the white dwarf became enshrouded in a dense shell of stripped gas that engulfed both stars, forming a rare structure called a common envelope. When that envelope finally dispersed, the ejection produced a separate gamma-ray flash observed by Fermi.

“These observations allow us to watch a stellar explosion in real time… Instead of seeing just a simple flash of light, we’re now uncovering the true complexity of how these explosions unfold,” said Elias Aydi, lead author of the study published in Nature Astronomy and a professor at Texas Tech University.

Coauthor Laura Chomiuk of Michigan State University added that novae act as “laboratories for extreme physics,” helping researchers connect the nuclear reactions on the white dwarf surface with the three-dimensional geometry of the ejecta and the high-energy radiation we detect from space.

Why This Matters — These combined CHARA, Fermi and Gemini observations demonstrate that novae are not simple, uniform blasts but are diverse in timescale, geometry and energy output. The results improve our understanding of mass transfer in binary systems, shock interactions that produce gamma rays, and the role of complex ejecta shapes in radiative processes. Continued interferometric monitoring promises to reveal more about how novae ignite, evolve and influence their surroundings.

Help us improve.