Gregor Johann Mendel, an Augustinian monk near present-day Brno, conducted controlled pea-plant experiments from 1856 to 1863 and studied roughly 28,000 plants. By tracking seven clear traits, he inferred three fundamental principles of inheritance: dominance, segregation, and independent assortment. His 1866 paper was largely overlooked during his life but was rediscovered in 1900, catalyzing the modern field of genetics.

How Gregor Mendel’s Pea Experiments Laid the Groundwork for Modern Genetics

Hidden for much of his life in a rural monastery near today’s Brno in the Czech Republic, Gregor Johann Mendel performed experiments that became the foundation of modern genetics.

Known today as the “father of modern genetics,” Mendel — an Augustinian monk of Austrian origin — did not begin his religious career in triumph. His mentor, Abbot Cyrill Napp, noted that Mendel had been judged unfit for parish duties because of “unconquerable timidity.” Still, Mendel’s practical experience on his family farm and coursework in science and mathematics at the University of Vienna made him an excellent choice to tend the monastery garden.

Why Peas?

Between 1856 and 1863 Mendel conducted carefully controlled hybridization experiments on the garden pea, Pisum sativum. He raised roughly 28,000 plants over eight years because peas offered ideal conditions for breeding experiments: they are inexpensive, produce many offspring, have easily observed traits, and can be self- or cross-pollinated in a controlled way. These features made it possible to identify clear statistical patterns across many individuals.

Methodical Observations

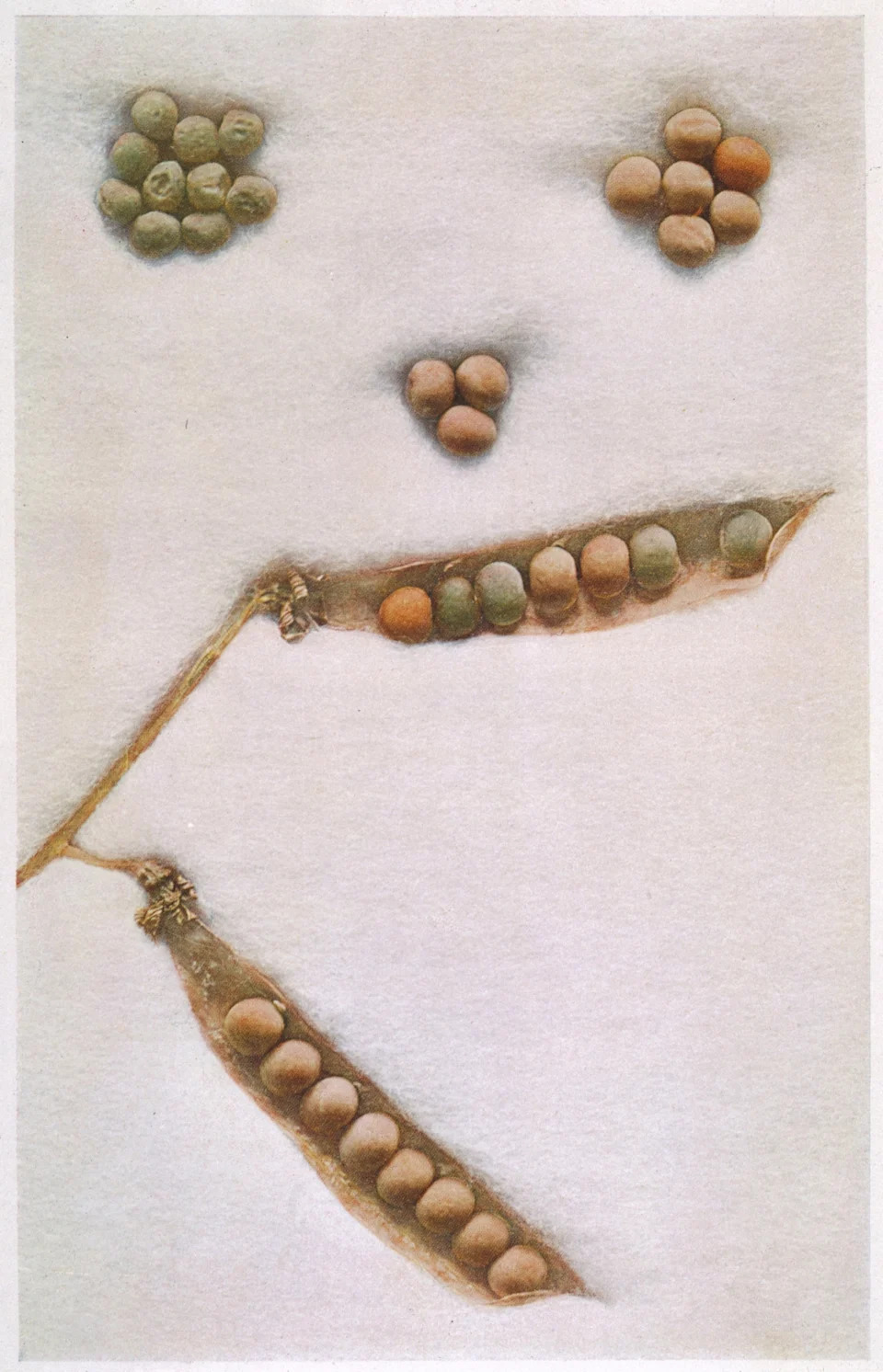

Mendel tracked seven discrete traits: seed shape; seed interior (cotyledon) color; seed coat color; pod shape; unripe pod color; flower position; and stem length. He recorded how these traits appeared when plants self-pollinated and when they were cross-pollinated. No detail was too small; his counts and ratios provided the empirical foundation for general principles.

Three Principles of Inheritance

He presented his results in two talks to the Natural Science Society of Brünn (Brno) on February 8 and March 8, 1865, and published a paper in 1866. That work described three principles that later became known as Mendel’s laws:

- Law of Dominance: Some variants (dominant traits) mask others (recessive traits) in hybrids.

- Law of Segregation: Two copies of a heritable factor separate so each gamete receives one copy.

- Law of Independent Assortment: Different traits are transmitted independently from one another (with some exceptions discovered later).

Although Mendel used terms like "factors" rather than "genes," his experimental evidence showed that heritable units behave as discrete entities rather than blending together.

Delayed Recognition

Mendel’s paper attracted little attention during his lifetime. He was relatively isolated from the wider scientific networks of the era and did not correspond with prominent figures such as Charles Darwin. In addition, heredity was not then a fashionable focus; evolutionary questions dominated mid-19th-century science.

After his death in 1884, interest in heredity and plant breeding grew. In 1900 three researchers working independently — Carl Correns, Hugo de Vries, and Erich von Tschermak — rediscovered Mendel’s findings, and the modern field of genetics began to form. The word "genetics" was proposed by William Bateson in 1905 and adopted at a 1906 conference; the term "gene" was coined by Wilhelm Johannsen in 1909.

Legacy

Mendel’s approach — controlled crosses, careful counting, and statistical reasoning — remains central to genetics and to understanding how traits pass through generations in plants, animals, and humans. His laws addressed a gap in Darwin’s theory by explaining how inheritance works at a basic level.

Months before he died, Mendel told a fellow monk: “My scientific work has brought me great joy and satisfaction; and I am convinced that it won't take long that the entire world will appreciate the results and meaning of my work.”

Help us improve.