New technologies allowing simultaneous recording of thousands of neurons plus real-time behavioral video are revealing how single cells and networks construct visual perception. Mice—though their eyes sit laterally—show an unexpected sensitivity to frontal visual fields and can be trained to report what they see. Behavioral state, environmental affordances and specific inhibitory neurons powerfully modulate cortical visual responses, and open data-sharing is accelerating discovery with direct relevance to human vision and visual disorders.

Gazing Into the Mind’s Eye: How Mice Reveal Hidden Mechanisms of Human Vision

Despite the old nursery rhyme about three blind mice, mice are far from visually inept. Research on how mice see is revealing precise, cell-level mechanisms of visual processing and showing how networks of neurons construct internal images of the world.

Why Mice Matter to Vision Science

I am a neuroscientist studying how neurons generate visual perception and how those processes break down in conditions such as autism. In my lab we "listen" to the electrical signals of neurons in the cerebral cortex, the brain's outer layer that dedicates a large portion of its circuitry to vision. Damage to the visual cortex can cause blindness and other visual deficits even when the eyes themselves are healthy.

New Tools, New Insights

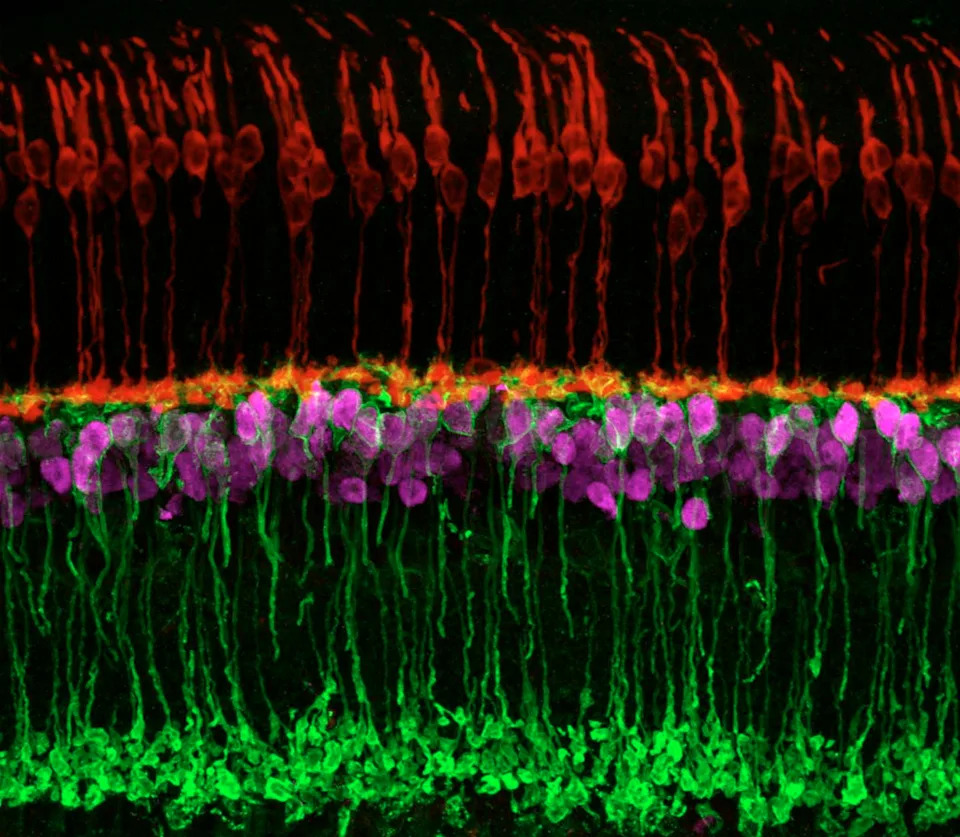

Understanding individual neurons and how they cooperate while the brain actively processes information has long been a central goal of neuroscience. Recent technological advances — especially in the mouse visual system — have brought us much closer to that goal. Laboratories can now record from thousands of neurons simultaneously and align those recordings with real-time video of a mouse's face, pupil and body movements, revealing how behavior and brain activity interact.

These improvements are like upgrading from a grainy single-microphone recording of a symphony to a pristine multi-track mix where every musician and every finger movement is audible.

Surprising Capabilities of Mouse Vision

Researchers once assumed mouse vision was coarse and slow. It turns out neurons in mouse visual cortex, like those in humans and other mammals, respond selectively to specific visual features and are especially precise when the animal is alert and awake. My colleagues and I — along with other groups — have shown that mice are particularly sensitive to stimuli appearing directly in front of them. This is striking because mouse eyes are lateral rather than forward-facing, yet mice demonstrate a frontal bias similar to that seen in primates and cats.

This frontal emphasis likely helps mice detect shadows, edges or approaching predators and improves their ability to hunt insects. Importantly, the central visual field is also most affected by aging and many human visual diseases, so mice are valuable models for studying and treating visual impairment.

Behavior, Context and Perception

Vision is not static. Behavioral state, environmental affordances and task demands strongly modulate visual processing. For example, my lab found that the speed at which visual signals reach cortex depends on the actions the environment permits: when a mouse sits on a platform that allows running, visual signals travel to cortex faster than when the same images are shown with the mouse in a stationary tube — even if the mouse remains still in both cases.

To link electrical signals to perception, researchers train mice to report what they see. Over the past decade, long-standing assumptions about rodent cognition have been overturned: mice learn reliably and can communicate perceived visual events through actions. They can release a lever to indicate a pattern has brightened or tilted, rotate a small wheel to center a visual stimulus on a screen, stop running and lick a water spout when a scene changes, or otherwise signal detection in controlled tasks.

Mice can also direct their visual processing to specific regions of the visual field. When they attend to a region, they respond faster and more accurately to stimuli there — but at a cost: unexpected stimuli elsewhere are detected more slowly. These patterns closely resemble human spatial attention.

Cell Types That Gate Perception

Specific classes of inhibitory neurons — cells that suppress activity — exert powerful control over visual signals. Artificially activating particular inhibitory neurons in mouse visual cortex can dramatically reduce or effectively "erase" perception of an image. Such experiments show that perception and action are tightly interwoven and that the same visual stimulus can evoke different neural responses depending on behavioral context (e.g., whether the mouse is moving, thirsty, or likely to detect the stimulus).

Big Data and Open Science

The surge in mouse visual-system research has dramatically increased the volume of high-quality data collected in single experiments. Major national and international centers have pioneered optical, electrical and biological tools to measure large neural ensembles and have made much of the resulting data openly available. This culture of data sharing accelerates replication, comparative analysis and discovery, and it supports development of computational methods needed to disentangle visual signals from behavioral influences.

Looking Forward

Advances in recording technology, behavioral training, cell-type-specific manipulation and open data are converging to provide an unprecedented view of how brains see. If the past decade is any indication, current discoveries are only the beginning. The humble, far-from-blind mouse will remain a leading model for unraveling the neural circuits and computations that underlie human vision.

Author: Bilal Haider, Georgia Institute of Technology.

Funding Disclosure: Research support from NIH and the Simons Foundation.