Researchers from Hebrew University analyzed over 700 Halafian pottery fragments from 29 sites (c. 6200–5500 B.C.) and found floral decorations with petal counts following a doubling sequence: 4, 8, 16, 32, 64. The patterns—reported in the Journal of World Prehistory—suggest an early cognitive shift toward symmetry and division rooted in village life. These visual designs imply mathematical thinking existed long before the advent of writing around 3000 B.C.

Ancient Pottery Reveals Early Mathematical Thinking: Geometric Petal Patterns on Halafian Vessels

Careful study of some of the oldest known plant-decorated ceramics shows that early farmers were using visual strategies that reflect mathematical thinking long before formal writing or number systems appeared.

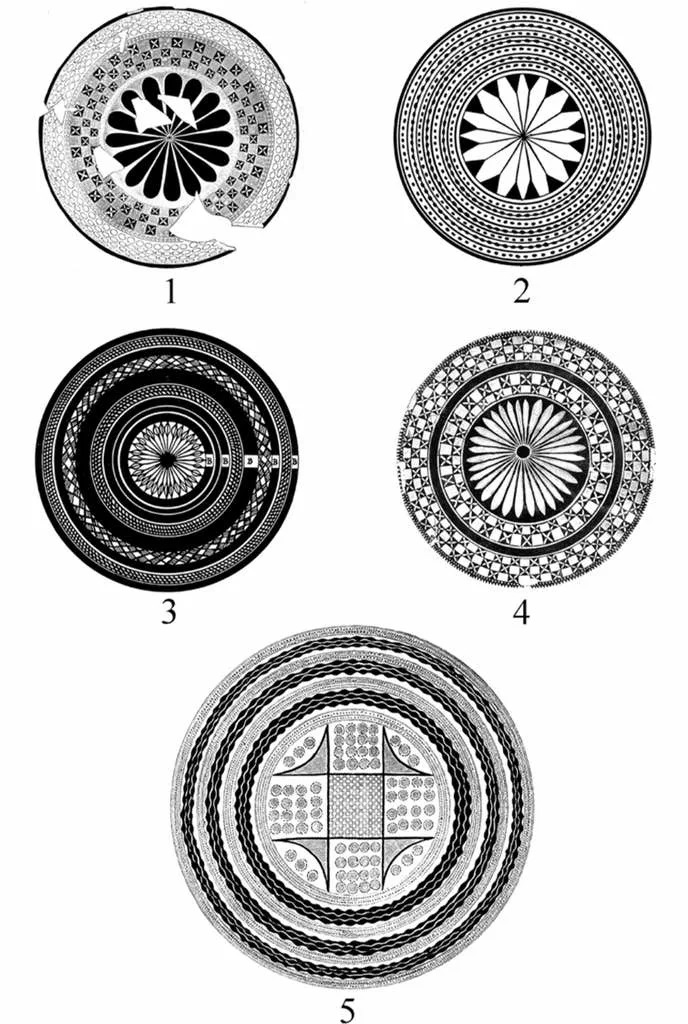

Archaeologists from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem examined more than 700 pottery fragments bearing botanical motifs from 29 Halafian sites in northern Mesopotamia dated to roughly 6200–5500 B.C. The researchers focused on painted floral designs and identified repeated petal counts that form clear geometric sequences.

Distinct Patterns and Counts

Across the fragments, bowls and vessels were decorated with petals arranged in repeated counts of 4, 8, 16, 32, and 64. These counts follow a doubling pattern (powers of two) rather than random ornament, indicating an organized approach to dividing circular space.

"These vessels represent the first moment in history when people chose to portray the botanical world as a subject worthy of artistic attention. It reflects a cognitive shift tied to village life and a growing awareness of symmetry and aesthetics,"— Hebrew University archaeologists Yosef Garfinkel and Sarah Krulwich.

Why This Matters

The researchers argue that the ability to divide space evenly likely had practical origins in everyday community life — for example, sharing harvests, allocating plots, or organizing communal tasks — and that such needs encouraged visualization of division, symmetry, and sequence. These visual conventions therefore represent early cognitive steps toward abstract mathematical concepts, occurring thousands of years before cuneiform writing arose in Mesopotamia around 3000 B.C.

Broader Significance

Published in the Journal of World Prehistory, the study connects village life, aesthetic choices, and the emergence of abstract thought in prehistory. The geometric floral motifs offer a tangible window into how prehistoric communities reasoned about proportion and organization through art.