New research in Science finds agricultural drones have spread rapidly worldwide, transforming spraying, seeding and monitoring. Modern drones carry up to 220 pounds (100 kg) and — often via hired service providers — are now accessible to many farmers despite wide price differences across countries. China leads adoption (≈250,000 drones), Thailand and the U.S. are growing quickly, and benefits include reduced chemical exposure and labor savings. Major caveats remain: chemical drift risks, potential worker displacement, and limited large-scale evidence on yield gains.

Agricultural Drones Are Spreading Fast — Saving Time, Cutting Risk, Raising New Questions

Drones have moved from niche gadgets into many parts of daily life over the past decade — from entertainment and health care to construction — and they are now rapidly reshaping how food is grown.

New research published in Science by social scientists studying agriculture and rural development documents how agricultural drones have proliferated worldwide, what farmers use them for, and why adoption has accelerated so quickly. The study also considers implications for farmers, ecosystems, the public, and policymakers.

Just a few years ago, agricultural drones were small, expensive and difficult to operate, limiting use to early adopters. Modern models can be flown immediately after purchase and can carry payloads up to 220 pounds (100 kg) — roughly the weight of two sacks of fertilizer. Prices vary markedly by country because of taxes, tariffs and shipping: similar equipment can cost US$20,000–30,000 in the United States, while comparable units are available for under US$10,000 in China.

Most farmers do not buy and operate drones themselves. Instead, they hire service providers — small businesses that supply pilots and drones for a fee — which has made drone services accessible and relatively affordable for many farms, including smallholders.

What Drones Do On Farms

Today’s agricultural drones act like flying tractors: modular platforms that perform multiple tasks with different attachments. Common uses include:

- Spraying pesticides and foliar fertilizers;

- Spreading fertilizer and sowing seed;

- Transporting produce and delivering fish feed;

- Painting greenhouse structures and other maintenance tasks;

- Monitoring livestock location and welfare;

- Mapping field topography and drainage; and

- Assessing crop health via sensors and imagery.

Where Adoption Is Growing

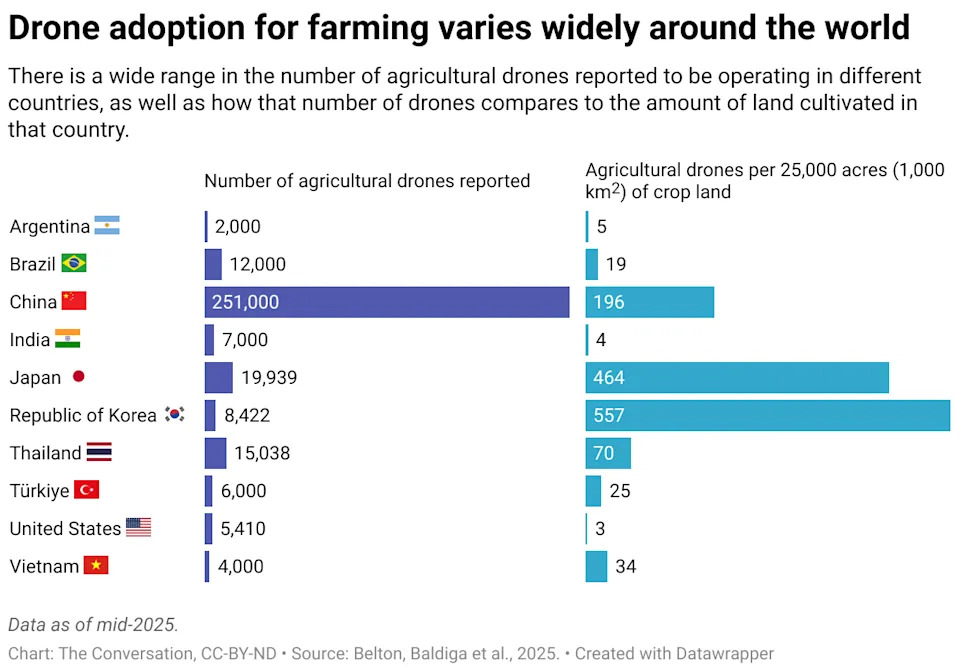

Drones have partially reversed the usual diffusion pattern of agricultural technology. Rather than spreading slowly from high-income countries down, drone adoption surged first in East Asia, then Southeast Asia, moved to Latin America, and later reached North America and Europe. China leads the world in manufacturing and adoption: after the first agriculture-specific quadcopter appeared in 2016, uptake rose rapidly and there are now an estimated >250,000 agricultural drones in use there.

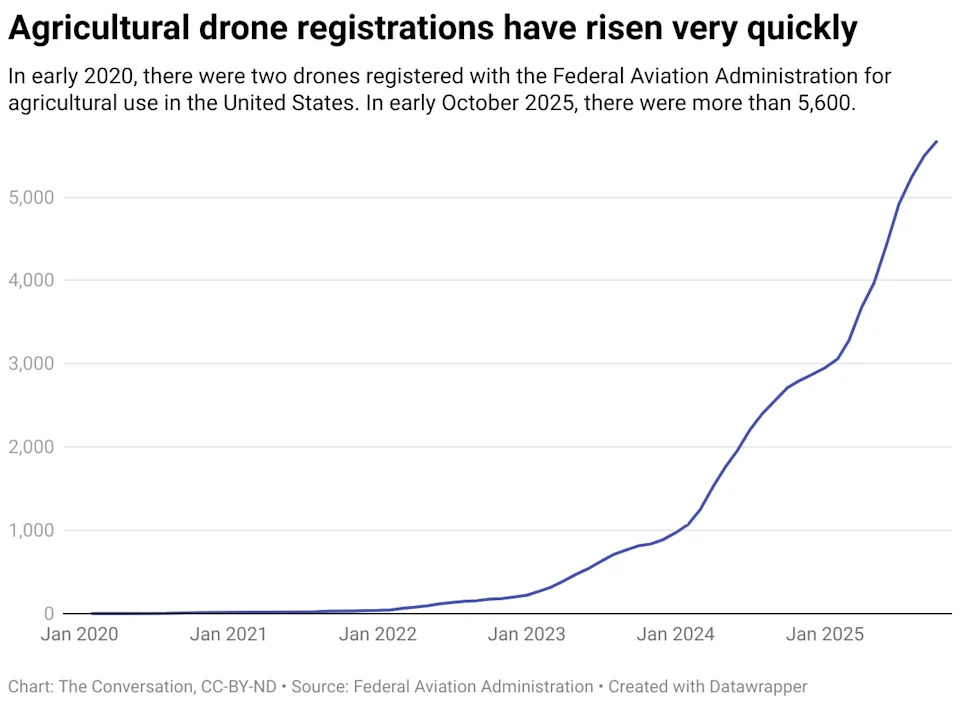

Other middle-income countries have adopted drones quickly. By 2023, drones were used on roughly 30% of Thailand’s farmland (up from almost none in 2019), mainly for pesticide application and spreading fertilizer. In the United States, Federal Aviation Administration registrations for agricultural drones rose from about 1,000 in January 2024 to roughly 5,500 by mid‑2025, though industry analysts say official figures likely undercount true use because some owners avoid complex registration procedures.

Benefits and Risks

Drones save time and money and reduce direct chemical exposure for farmers and farmworkers who previously applied agrochemicals by hand with backpack sprayers. Smallholders — farms under 5 acres (2 hectares), which account for about 85% of farms globally — can avoid hazardous manual spraying or paying labor for that work. Mechanization also creates new skilled rural jobs for drone pilots, often attracting younger workers.

However, adoption brings risks and trade-offs. Drones typically spray from a height of at least 6 feet (2 meters); if operated improperly they can cause chemical drift to neighboring fields, waterways or bystanders, harming people, crops and ecosystems. Mechanization can also displace labor: one Chinese estimate suggests drones can spray 10–25 acres (4–10 hectares) per hour — roughly the work of 30–100 manual sprayers — creating potential livelihood disruptions that governments may need to address.

Proponents also point to efficiency gains: drones can apply fertilizers and seed more evenly, reduce in-field crop damage and use less energy than large tractors. Together these factors could increase yields per acre while reducing resource inputs, a concept agricultural scientists call "sustainable intensification." But robust, large-scale evidence on yield improvements from drone-assisted farming remains limited; much current reporting is anecdotal, from small trials, or from industry studies.

What Comes Next

The drone revolution is transforming farming faster than many previous technologies. Millions of farmers worldwide have adopted drones in only a few years. Early signs point to important benefits — improved efficiency, safer working conditions and new rural employment opportunities — but many open questions remain: How large and persistent are yield and sustainability gains? How should governments regulate drone safety, chemical use and data privacy? And how can policies support workers displaced by mechanization?

Authors: Ben Belton and Leo Baldiga, Michigan State University. The authors report no conflicts of interest with companies that would benefit from these findings.

Help us improve.