An interdisciplinary team spent about 40 hours at sea with Marshallese navigators to study wave‑piloting — an ancestral skill of reading swells, wind and canoe motion to find distant atolls. The researchers used mobile eye tracking, 360° motion capture and brain monitoring during a two‑day voyage, with participants marking their perceived positions every 30 minutes. The project aims both to map the neural basis of open‑ocean navigation and to support transmission of cultural knowledge as rising seas threaten the Marshall Islands.

How Marshall Islanders ‘Feel the Ocean’: Scientists Study Ancient Wave‑Piloting

This past summer, an interdisciplinary team of neuroscientists, anthropologists, philosophers, oceanographers and Marshallese navigators spent roughly 40 hours at sea to investigate how indigenous sailors navigate by "feeling the ocean." Sailing between the low-lying atolls that stretch between Hawaii and Australia, the Marshallese crews declined to use GPS or sextants and relied on the long-practiced skill of wave‑piloting.

Reading swells, wind and canoe motion

For centuries, master navigators have interpreted the feel and sight of waves, subtle shifts in swell, wind patterns and the canoe's motion to detect islands more than 50 km (about 31 miles) away. The Marshall Islands comprise 29 atolls that often rise only a few feet above the water and can be nearly invisible until approached closely.

Tradition, loss and revival

That ancestral expertise nearly disappeared after the displacement of communities during U.S. nuclear testing in the 1940s and 1950s, which disrupted the transmission of traditional skills. A small group of custodians has worked to keep the practice alive; a central figure in the research is Alson Kelen, director of a local canoe‑building school, who learned wave‑piloting from his cousin, Captain Korent Joe, one of the last fully trained master navigators.

The expedition and scientific approach

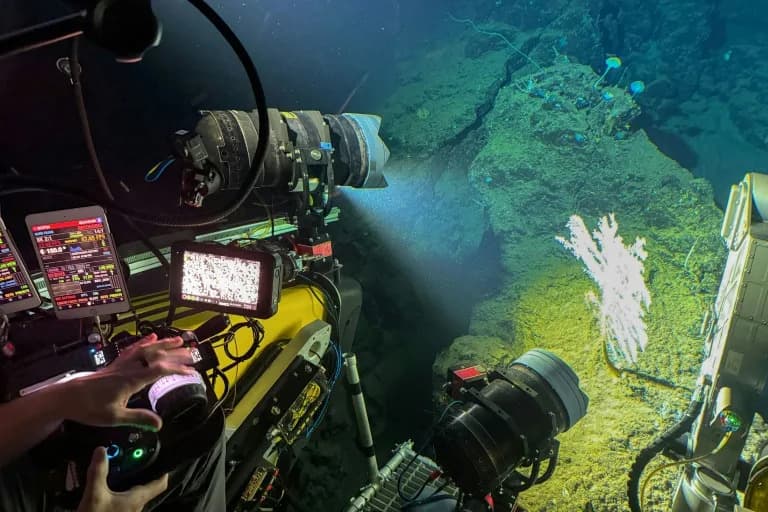

Over a two-day voyage this summer, researchers collected synchronized behavioral and environmental data using mobile eye tracking, 360° motion capture, heart‑rate and brain‑activity monitoring, and repeated mapping tasks. Every 30 minutes, everyone on board marked their perceived position on a chart and noted the direction from which the waves seemed to come. The project involved researchers from several universities working alongside the navigators to identify which oceanic cues experts attend to and how those cues are represented in the brain.

Hugo Spiers, a lead investigator with decades of navigation research experience, said he was disoriented by the open ocean: "I found it extremely hard to know where I was." For Marshallese sailors, the same environment is read like a familiar map.

Why it matters

Beyond mapping neural mechanisms of open‑ocean navigation, the study seeks to help transmit cultural knowledge at a time when climate change and rising seas threaten the Marshall Islands. The team plans to publish its full findings next summer.

Help us improve.