Richard Fishacre, a 13th-century Dominican at Oxford, argued that planets and stars are made from the same four terrestrial elements rather than an immutable "fifth element," using observations of light and colour. He pointed to planetary hues and the Moon's behaviour during eclipses as evidence, and warned his contemporaries he would face criticism. Modern astronomy has vindicated his intuition: transmission spectroscopy with instruments like the James Webb Space Telescope detects molecules such as water and sulphur dioxide on exoplanets by analysing subtle changes in light.

How a 13th-Century Oxford Friar Used Light and Colour to Challenge the Heavens

In the 1240s Richard Fishacre, a Dominican friar teaching at Oxford, argued that the stars and planets are made of the same basic elements found on Earth. Working without telescopes or rock samples, Fishacre reached this conclusion by thinking carefully about the behaviour of light and colour — an approach that, in principle, echoes methods used by modern space telescopes.

Medieval consensus: quintessence and the celestial spheres

Medieval natural philosophy, following Aristotle, held that the heavens were composed of a special, perfectly transparent substance often called the "fifth element" or "quintessence" (quinta essentia). This celestial matter was thought to be immutable and to form the nine concentric spheres encircling Earth, with each of the inner spheres carrying a planet and the outer spheres containing the stars.

Fishacre's argument from light and colour

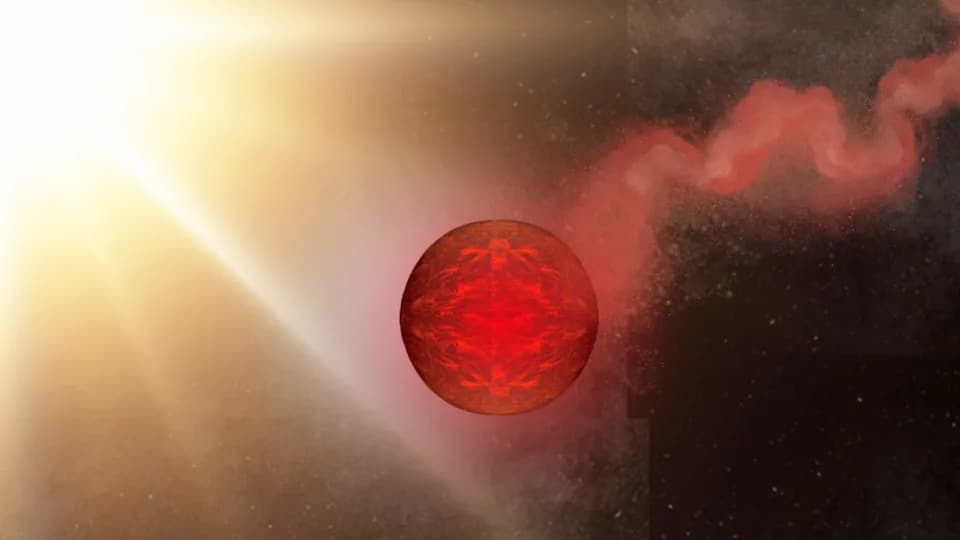

Fishacre rejected the idea that planets and stars were made of a unique, transparent substance. He observed that colour typically arises from opaque bodies, and that opacity implies a composite structure — made from two or more of the four terrestrial elements (earth, water, air, fire). Yet planets and some stars show faint but distinct colours: Mars appears red, Venus yellow. To Fishacre, these hues suggested that those bodies were composite rather than purely transparent.

He found his clearest analogy in the Moon. The Moon has a definite colour and, during eclipses, it can intervene between the Sun and Earth. If it were made of perfectly transparent quintessence — even in a dense form — sunlight would be expected to pass through it much as it passes through glass. Because that does not occur, Fishacre concluded the Moon must be composed of the same kinds of elements found on Earth. From the Moon, the lowest celestial body, he inferred the same for other planets and stars.

"If we posit this position," he warned, "then they, that crowd of Aristotelian know-it-alls (scioli aristoteli), will cry out and stone us."

His skepticism provoked opposition. In 1250 St Bonaventure publicly denounced such challenges to Aristotelian doctrine at the University of Paris, ridiculing those who questioned the celestial fifth element.

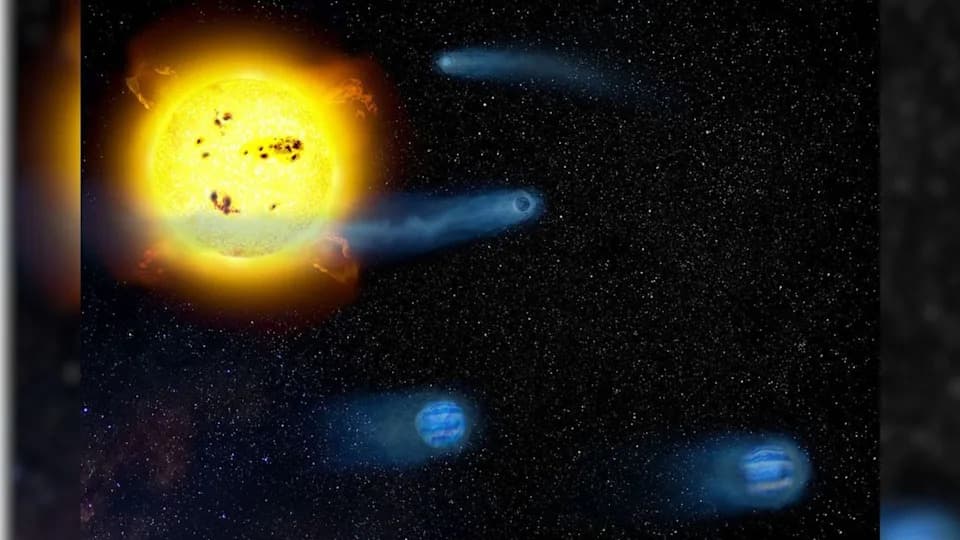

Modern vindication: light still reveals composition

Contemporary astrophysics has shown that Fishacre's intuition was right in essence: stars and planets are made primarily of the same elements and compounds found on Earth, not a mystical fifth essence. A modern analogue of Fishacre's reasoning is transmission spectroscopy, used by instruments such as the James Webb Space Telescope. When a planet passes in front of its star, starlight filters through the planet's atmosphere; molecules and atoms in that atmosphere absorb light at characteristic wavelengths, producing subtle changes in brightness and colour. These spectral fingerprints let scientists identify water vapour, carbon dioxide, sulphur compounds and many other species.

For example, observations with the James Webb Space Telescope have identified water and sulphur dioxide in the atmosphere of the Neptune-like exoplanet TOI-421 b, about 244 light-years away. That detection rests on the same basic idea Fishacre used: changes in light and colour reveal the presence of particular materials.

Why this matters

Fishacre's argument is a reminder that careful, principled reasoning from observation can anticipate techniques developed centuries later. Nearly 800 years on, astronomers still use light and colour to probe distant worlds and show that the universe shares many of the same elemental building blocks as our planet.

Help us improve.