Veerabhadran Ramanathan discovered in the 1970s that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) are extremely potent greenhouse gases, with a single molecule able to trap as much heat as thousands of CO2 molecules. His 1975 paper in Science helped broaden climate science beyond CO2 and influenced policy responses such as the 1987 Montreal Protocol. Over decades, Ramanathan combined observations and modeling to show how clouds cool the planet, how water vapor amplifies CO2 warming, and how air pollution — including a 3‑km thick brown cloud over South Asia — affects climate and health.

The Accidental Climate Scientist Who Revealed a Hidden Driver of Global Warming

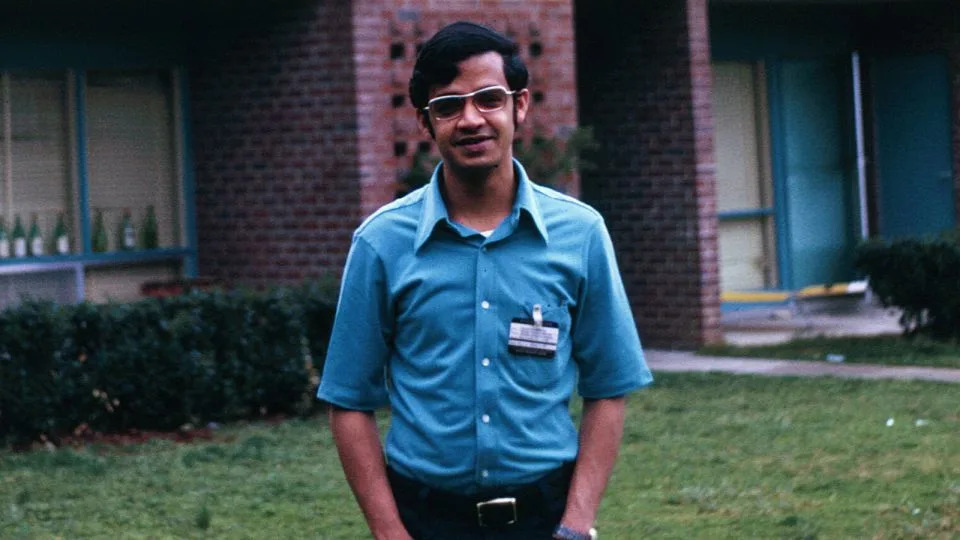

Veerabhadran Ramanathan, an Indian-born atmospheric scientist, transformed our understanding of Earth’s climate after an off-hours discovery in the 1970s. While a postdoctoral researcher at NASA Langley, he found that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) — then common in refrigerators, air conditioners and aerosol sprays — are extremely powerful greenhouse gases. His work, later published in Science and highlighted by The New York Times, helped broaden climate science beyond carbon dioxide and influenced international policy.

From Refrigerators to Global Climate

Ramanathan’s first exposure to CFCs came during an early job inspecting refrigerator seals in India. As a visiting researcher in the United States, he spent nights calculating how various trace gases absorb heat. To his surprise, his results showed that a single CFC molecule could trap as much heat as many thousands of carbon dioxide molecules. He repeated the calculations for months and—convinced by the evidence—submitted his findings to the journal Science, where they were published in 1975.

Scientific Impact and Policy Consequences

The idea that non‑CO2 gases could drive significant warming shifted the focus of climate research. Ramanathan and colleagues later expanded the list of important trace gases to include methane and nitrous oxide, showing that these gases could speed the onset of dangerous warming. Their work helped motivate restrictions on CFC production; the 1987 Montreal Protocol phased out many CFCs and, according to recent estimates, likely prevented up to about 1 °C of additional warming that would otherwise have occurred.

Observations, Clouds and Pollution

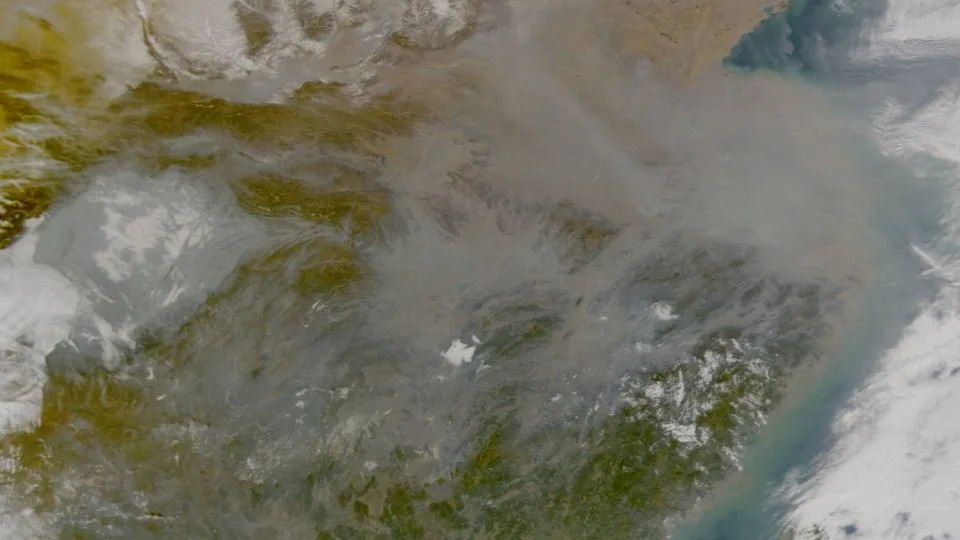

Beyond the 1970s paper, Ramanathan’s long career combined theory with direct observation. Using satellites, balloons, drones and ships, he confirmed and refined climate model predictions. He was among the first to demonstrate that clouds can have a net cooling effect and to document how water vapor amplifies carbon dioxide–driven warming. He also led research that revealed an extensive 3‑kilometer‑thick “atmospheric brown cloud” over the Indian subcontinent, showing how air pollution can temporarily mask some warming while creating severe regional health and climate impacts.

Science, Ethics and Public Engagement

Ramanathan’s contributions have been widely recognized: he is a Distinguished Research Professor at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, a former council member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences advising three popes, and a recent recipient of the Crafoord Prize from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Now in his eighties, he combines measured personal low‑carbon choices with an emphasis on political action: he urges young people to elect climate‑friendly leaders and to communicate using reliable, data‑based science.

Quote: “I was just a postdoc immigrant from India. I didn’t know if I should tell NASA about this or not. I just sent the paper off,” Ramanathan later recalled—an anecdote that underlines how curiosity and persistence can change scientific history.

Ramanathan’s story is a reminder that breakthroughs often come from connecting unexpected dots across disciplines—and that science can directly inform policy choices that protect both the planet and vulnerable communities.

Help us improve.