The EPA has paused converting health benefits—such as avoided deaths and hospital visits—into dollar values for rules targeting PM2.5 and ozone, citing modeling uncertainty. The move was revealed in an economic review of power-plant rules and has drawn criticism from former EPA officials and public-health experts. They warn that omitting monetized health benefits while keeping compliance costs in dollars will bias decisions toward weaker regulation and could harm air quality; the Biden-era PM2.5 rule was estimated to yield up to $46 billion in health benefits by 2032.

EPA Stops Putting Dollar Value On Lives Saved From PM2.5 And Ozone — Experts Warn Of Health Risks

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has announced it will stop assigning dollar values to certain human-health benefits—such as lives saved and avoided hospital visits—when evaluating regulations for fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and ground-level ozone. The change, included in an economic review of final power-plant pollution rules published this month, is intended to address modeling uncertainty. Critics say it could skew policymaking toward weaker protections and worse air quality.

What the Agency Changed

The EPA says it will pause monetizing the health benefits of reductions in PM2.5 and ozone "until the Agency is confident enough in the modeling to properly monetize those impacts." In practice, that means the benefits side of the traditional cost-benefit analysis—often expressed in dollars for avoided hospitalizations, illnesses and premature deaths—will be left un-monetized for now.

Why This Matters

When setting pollution standards, regulators compare the dollar costs of compliance (for example, installing emission controls) with the dollar value of expected benefits (fewer sick days, avoided hospital visits, longer lives). Removing the dollar value from the benefits column while leaving compliance costs in dollars makes apples-to-apples comparisons impossible, critics warn, and could bias decisions against more protective rules.

Under the Biden administration, for example, the EPA estimated that enforcing tighter PM2.5 standards issued in 2024 would produce up to $46 billion in health benefits by 2032—far exceeding projected compliance costs. Removing that monetized figure effectively removes a key justification for stricter standards from public accounting.

Expert Reactions

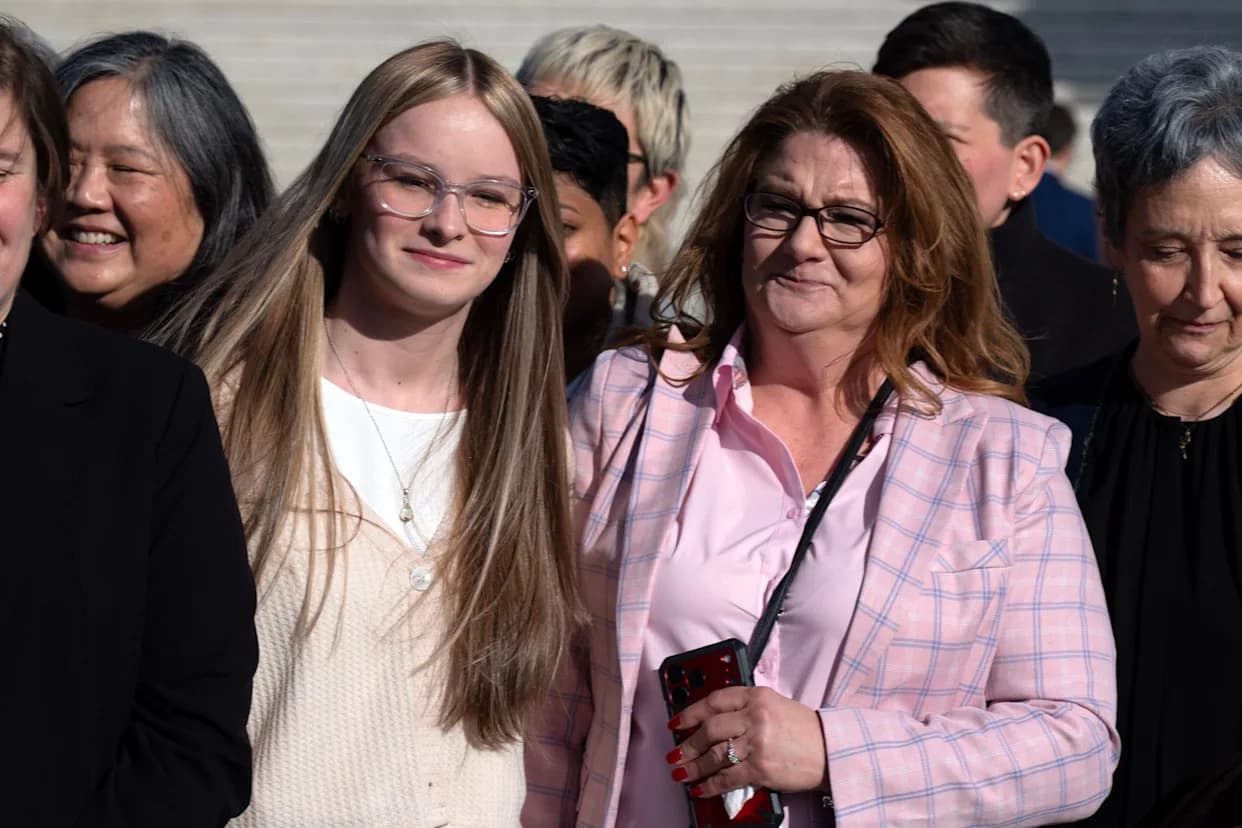

“There is a lot of science that shows very clearly that being exposed to increasing levels of PM2.5 has significant health impacts,” said Janet McCabe, who served as the EPA's deputy administrator under President Joe Biden.

Public-health and policy experts argue the change could weaken enforcement. Christa Hasenkopf, director of the Clean Air Program at the University of Chicago's Energy Policy Institute, noted that without monetized benefits, regulators cannot make direct dollar-to-dollar comparisons of costs and benefits. Joseph Goffman, a former assistant administrator for the EPA's Office of Air and Radiation, called the step "convenient" for efforts to loosen particulate-matter standards.

Broader Context

Observers place this decision within a broader shift at the EPA under the current administration. The agency has closed its Office of Research and Development, which provided scientific analysis to support rulemaking, and has moved to narrow or dismantle certain legal frameworks used to address air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. Reduced scientific and economic analysis could limit agency accountability and make it easier to roll back regulations favored by industry.

Potential Consequences

Experts warn that unless the agency develops an alternative, reliable way to monetize health benefits, air-quality improvements could stall or reverse. Measured across populations, long-term exposure to air pollution shortens lives; current estimates attribute roughly 135,000 premature deaths in the United States each year to air pollution. Without clear accounting of those human impacts in economic terms, policymakers risk undervaluing crucial public-health gains.

What To Watch: Whether the EPA develops new modeling methods to reintroduce monetized health benefits into cost-benefit analyses, and how courts and Congress respond if policy decisions appear to rest on incomplete accounting of public-health impacts.

Help us improve.