Two alleged politically motivated killings — the Dec. 4, 2024, slaying of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson in Manhattan and the September shooting at Utah Valley University targeting commentator Charlie Kirk — reveal why state law doesn’t always permit the death penalty. New York attempted a terrorism enhancement that was dismissed; Utah relied on an aggravated-murder charge citing risk to the crowd. Experts note modern capital statutes require specific aggravators beyond premeditation, and federal charges can still expose defendants to harsher penalties.

Why Politically Motivated Killings Don’t Automatically Qualify For The Death Penalty

Two recent alleged assassination plots — one in Manhattan and one at a Utah university — highlight a legal gap that can prevent prosecutors from seeking the harshest state penalties even when attacks appear politically motivated. Evidence in both cases reportedly included shell casings engraved with political messages, suggesting deliberate intent. Yet state statutes in New York and Utah place limits on when the death penalty or life without parole can be pursued.

The Cases

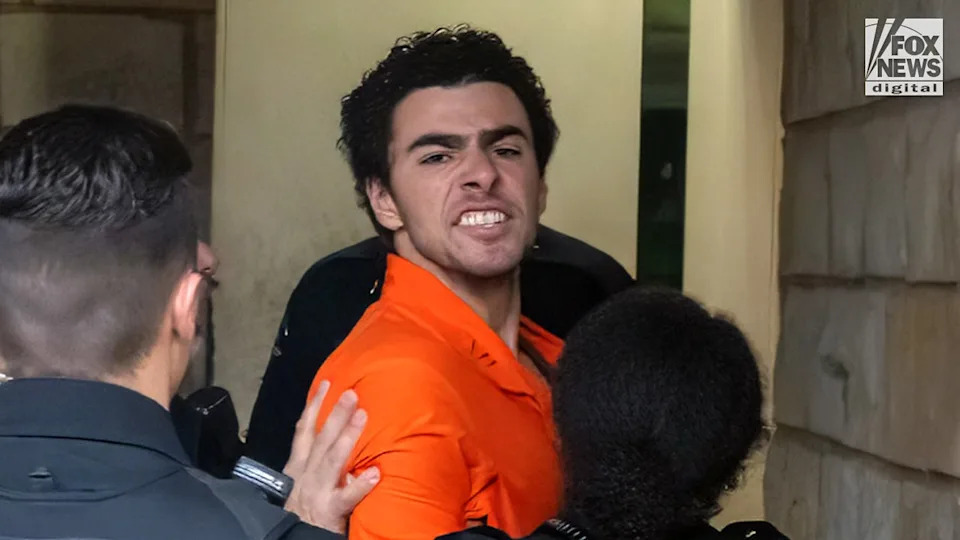

Prosecutors allege that on Dec. 4, 2024, 27-year-old Luigi Mangione shot UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson, 50, in Manhattan and left shell casings marked with political messages. In a separate incident months earlier, authorities accused 22-year-old Tyler Robinson of firing at conservative commentator Charlie Kirk, 31, as Kirk spoke at Utah Valley University; investigators say Robinson also left casings with engraved messages.

Why States Sometimes Can’t Seek Capital Punishment

State capital statutes typically require specific aggravating factors beyond premeditation to justify death or life-without-parole sentences. Common aggravators include killing a police officer, a child, an elected official, or multiple victims. Business leaders or media figures who are not public officeholders often do not fall into those enumerated categories, even when a political motive is alleged.

How Prosecutors Responded

In New York, Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg’s office tried to invoke a terrorism-enhancement to support a first-degree murder charge that could carry life without parole for Mangione. A judge later rejected that enhancement, leaving Mangione facing a second-degree murder charge that permits the possibility of parole. In Utah, prosecutors sought the death penalty by charging Robinson with aggravated murder, arguing that firing at a crowd created a great risk of death to others — an aggravator under Utah law.

Legal Hurdles And Expected Defenses

Defense teams and legal experts have identified several likely points of contention. In Utah, critics will point to reports that only a single shot was fired and argue it may not prove the requisite risk to the crowd. In New York, some commentators contend the facts fit the state terrorism statute, while the judge disagreed. Observers also note the danger of stretching existing statutes to fit politically motivated killings: such strategies can invite reversals on appeal and raise fairness concerns for defendants and victims’ families alike.

“There has to be something more,” says former prosecutor and capital-punishment author Matt Mangino of the modern approach to death-penalty law, which emerged after concerns about arbitrary application in the 1970s.

Federal Exposure And Broader Debate

Even where state law limits the penalties, federal charges can sometimes expose defendants to harsher punishments. Mangione also faces pending federal charges related to Thompson’s slaying that could carry capital exposure. The cases have renewed debate about how the criminal-justice system defines "assassination" and whether current legal categories adequately capture politically motivated killings of influential but non-officeholding figures.

As these prosecutions move forward, courts will weigh statutory language, evidentiary thresholds, and constitutional protections — and those rulings could shape how future politically motivated attacks are charged and punished.

Help us improve.