The archaeological survey of the Kitsissut (Carey) Islands off northwest Greenland recorded nearly 300 features, including 15 Paleo‑Inuit tent‑ring dwellings on Isbjørne Island. Radiocarbon dating of bone places occupation at about 4,000–4,475 years ago, indicating repeated seasonal visits. The minimum sea crossing from the mainland is ~33 miles (53 km) and would have taken roughly 12 hours in skin‑covered boats, suggesting summer voyages to harvest seabirds, especially thick‑billed murres. Researchers conclude the islands and their surrounding polynya were important recurring destinations and centers of maritime innovation.

Paleo‑Inuit Made Risky 33‑Mile Sea Crossings to Remote Greenland Islands 4,000–4,475 Years Ago, Study Finds

Archaeologists report compelling evidence that Paleo‑Inuit groups repeatedly crossed hazardous open Arctic seas to reach the remote Kitsissut (Carey) Islands off northwest Greenland roughly 4,000–4,475 years ago. A recent survey documented nearly 300 archaeological features across three islands, including a dense cluster of 15 tent‑ring dwellings on Isbjørne Island, indicating repeated seasonal visits rather than a single accidental landing.

Location and environment. Kitsissut, the westernmost point of Greenland, comprises six small islands situated within a polynya — a semi‑permanent area of open water surrounded by sea ice that concentrates marine life and attracts seabird colonies. Contemporary Inuit have long regarded the islands as important for seabird hunting and egg collecting, which motivated the archaeological investigation.

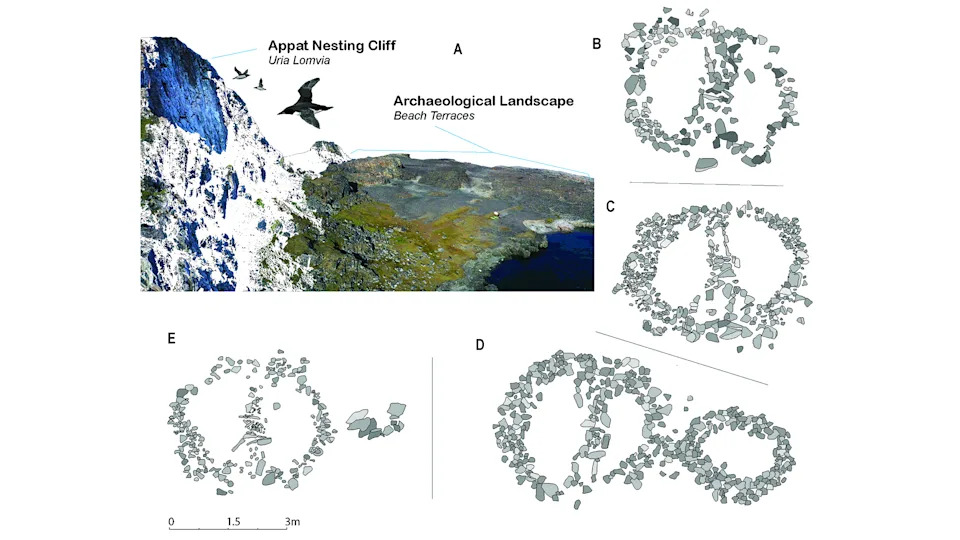

What was found. The team recorded close to 300 features, the largest concentration being 15 stone‑ring tent foundations at the tip of Isbjørne Island. These rings mark where skin‑covered tents once stood, typically with a hearth at the center. Radiocarbon dating of an animal bone from one ring yielded an age of about 4,000–4,475 years ago.

Maritime challenge and technology. The minimum open‑water crossing from the mainland to Isbjørne Island is roughly 33 miles (53 km). The route is exposed to erratic crosswinds, dense fog and strong mixing currents, and the researchers estimate the voyage would have taken on the order of 12 hours in the traditional wood‑framed, skin‑covered watercraft used by Paleo‑Inuit. These conditions imply travel during the brief Arctic summer.

Why they came. Many tent rings lie directly below thick‑billed murre (Uria lomvia) nesting cliffs, and numerous murre bones were recovered in association with the sites. The evidence suggests the islands were used to harvest seabirds and eggs. The number and clustering of tent rings point to visits by sizable groups — possibly whole communities — rather than small, transient hunting parties.

"In a regional perspective, it is a lot of tent rings in one place, indeed one of the largest concentrations," said Matthew Walls, lead author and archaeologist at the University of Calgary. "It wasn't just a one‑off visit — Kitsissut appears to have been a place of return."

Broader significance. The findings highlight the Paleo‑Inuit's advanced seafaring knowledge and watercraft skills and underline a strong maritime orientation in their lifeways. Rather than simply functioning as a travel corridor, the researchers argue Kitsissut and its polynya operated as a recurrent seasonal hub for resource exploitation and maritime innovation.

Next steps. The authors note that further excavation could reveal more about community composition, seasonality and on‑site activities, offering a fuller picture of life on these distant Arctic islands thousands of years ago.

Help us improve.